Michael Koresky

Lorna’s Silence, while as lean and tight as any of their films, is also closer to a traditional narrative than they’ve ever been, with its curt, pointed scenes that push the story forward, its reliance on the close-up (rather than their patented over-the-shoulder POV style), and its occasional shot/reverse shot set-ups.

If ever a movie called for a patented millennial ALL-CAPS live-blogged text review, it would have to be Jaume Collet-Serra’s Orphan, or, as it will likely forever be known moving forward, OMG, DID YOU SEE ORPHAN WTF?!.

It’s hard to imagine a receptive audience for Max Mayer’s Adam as anyone other than moony-eyed thirteen-year-old girls—not that Fox Searchlight would ever admit that this should be its target demographic.

For a filmmaker like Claire Denis, who traffics less in incident than in fleeting instants, less in the familiar comforts of story than in the ever-mounting pleasures of seduction, cinema is marked by slipperiness.

Claire Denis’s films usually stray so widely from anything resembling newsworthy topics that her new White Material, an experiential foray into a contemporary African crisis, risks being categorized as merely “topical.”

Even amidst Ben and Andrew’s incessant, and only occasionally amusing, hand-wringing over their rash decision, never did I believe that these were two real dudes seriously considering going through with their pointless triple-dog dare.

At first, the whiff of Kaurismäki and Jarmusch is undeniably pungent, but Eimbcke keeps peeling back his layers of detachment one by one, until something pure and plangent remains onscreen.

Perhaps to truly define and sculpt an image of contemporary urban living as experienced by a city’s most peripheral denizens, a filmmaker needs to get past the concreteness of the faces, sidewalks, and buildings and move into something more malleable.

Stephen Frears’s version of Colette’s novel Chéri, adapted by Christopher Hampton, is ostensibly an examination of an aging Michelle Pfeiffer.

Yes, Woody Allen’s fortieth feature, Whatever Works, is Just Like All the Rest. So what? That should take a critic of average intelligence about thirty seconds to ascertain, or less if you want to start with the white-on-black credit typography; there’s still a whole movie left.

Sex Positive is bracing in its honesty: towards the end of the film, a handful of the film’s interviewees admit to never having heard of Richard Berkowitz.

Certainly for the hordes of fans who have felt twinges of disappointment by his big-studio shenanigans in the past decade or so (regardless of his continued slavishness to his comic-book demographic), the very possibility of Raimi going back to his roots is a cause for salivation.

Is the beginning even the beginning? It’s a question I posed in my head about halfway through Jim Jarmusch’s The Limits of Control, first literally and later philosophically.

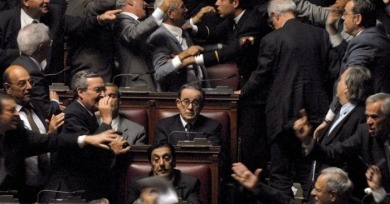

l Divo seems, to these foreign eyes, an unnecessarily demonic affair, and the heavy thumb that Sorrentino keeps on his characters often makes his drama inert.

Not every chintzy Hollywood comedy that comes down the pike need be held up as an example of the State of Contemporary Entertainment, but a film like Jody Hill’s pretend-flippant, zeitgeist-baiting Observe and Report practically begs for serious consideration.

The only true limitation we gave our writers was that their selected films hail from a year no earlier than 2000: this is an investigation into gay representation specifically in the Bush era.

A common, if under the radar, attack lobbed at Van Sant’s film is that by leaving out the facts of Harvey Milk’s alleged promiscuity, it reveals a biased agenda, to whitewash his life in the name of martyrdom.

With his likeable, sentimental narratives, Majidi has been somewhat simple to write off, then, as his takes on family and tradition cross cultural borders with ease, resulting in some critics’ accusations of patronization, if not moralism.

Two tired, and seemingly opposed, trademarks of recent American independent cinema make for a deadly combination in Matt Aselton’s Gigantic. It’s an arch, self-aware puppy-dog love story, shot through with an overly aestheticized, almost clinical detachment.

His cinema is purely one of desire, surveying a new generation of young gay men whose angst comes not as much from external social pressures and the threat of societal role-playing as the pangs and thumps of the heart.