By flattening her bitterness and vengeful desire into an ahistorical and essentialized feminine disposition, Gyllenhaal’s portrayal of Shelley at once diminishes the author’s stature in literary history and fails to address any of the documented ways in which she has been wronged.

After ten or 15 minutes of rave-rainbowed shapes liquefying into gyrating video frames to the strobing beat of the music, the thought occurs that this may be, for better or worse, the MTV generation’s smartest answer to Paul Sharits.

Below the Clouds, though set in a relatively small area hunkered uneasily between the Phlegraean Fields to the West and towering Vesuvius to the East, is populated with incidents that invite the viewer to contemplate a broader, global apocalyptic moment.

What Does That Nature Say to You is notable not because it eschews dramatic material but because it withholds the usual means of discerning which details are relevant or irrelevant to the nominal drama.

In Queens, we read those magazines at the Indian grocery between shelves of rice and spices. Bollywood did not feel distant. It felt personal, as if it were working through how complex love, marriage, and commitment could be.

The film so insists on a clean break between libidinous and infantile that the film neuters the ambivalent eroticism fueling the novel.

Target would eventually find its way on the Internet, where its charmingly unrefined style helped it fit in with the plethora of amateur video diaries, but it crucially exists within and beyond its particular early-to-mid-’90s moment.

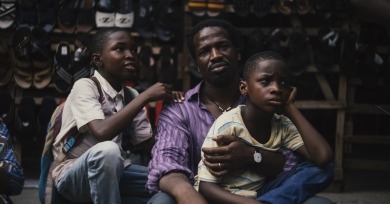

Both of us always mention in our master classes or panels with cinema students to choose a subject that you really like for your projects because you are not sure how long you are going to spend on the project. Better to choose something that is very close to your heart.

The filmmakers maintain that the character is not a direct representation of the father they barely knew but a broader symbol of paternal strength and the fallible masculinity it obscures. The resulting work is much less a memory piece than a sustained act of mournful imagining,

The palette used throughout often reflects the muted shades of English fine china and porcelain popular during the Napoleonic era. Although the bulkiness of the Technicolor camera limited the dynamism that had marked Mamoulian’s previous work, his playfulness with color in Becky Sharp exudes the energy of a kid trying out a new toy.

It is impossible to ignore that the decline of traditional print journalism has resulted in an eradication, and deterioration in quality, of the sort of work at which Hersh excelled. When Hersh cracks a self-deprecating joke about how he’s “slumming it” on Substack now, it’s hard not to despair.

It is outwardly dispiriting and disarmingly sweet, narratively brutal and formally subdued, thematically outré and structurally prosaic. It articulates taboo subjects with the matter-of-factness of the everyday, equally in tune with the absurdity and mundanity of the relationship it portrays.

The point here is not the destination or the shellshocked wanderers, but the conflagrations of sounds and visuals Laxe conjures along the way.

The history of these tools and the concurrent development of new animation techniques demonstrate how closely artistic concerns and technical logistics are married in filmmaking. The multiplane camera is also an effective synecdoche for the system Walt Disney molded his studio into.