More Than Human

Ela Bittencourt on the Flaherty NYC Program, 2020–2021

The Flaherty NYC Program (To Feel, To Feel More, To Feel More Than) plays Friday April 2, 8pm (ET) and Saturday, April 3, 4pm (ET), featuring live conversations with the filmmakers.

In “To Feel, To Feel More, To Feel More Than,” published in his essay collection Black and Blur, the poet and scholar Fred Moten asks, “What if the human is nothing other than this constancy of being both more and less than itself?” From James Baldwin, Adrian Piper, and Lygia Clark to Louis Armstrong, Moten covers a vast cultural ground in his compact essay, whose threads riff on each other, like in a jazz composition. In it, Moten affirms the earthliness of human experience (“to feel less than human”) as intricately connected to its immeasurability (“to feel more” and to “feel more than human”); at one point, he frames this immeasurability lyrically as, “the sheer, slurred, smeared, swarmed seriality of mechanical buzz, horticultural blur, geometrical blend, an induced feeling’s indeterminate seeing.” This indetermination and embeddedness in materiality are then the drivers of our human “autoexcessive feel.”

The new Flaherty NYC film program, named after Moten’s essay and comprising two screenings of experimental shorts curated by Flaherty’s three 2020–2021 programmers-in-residence, Devon Narine-Singh, Suneil Sanzgiri, and Alia Ayman, highlights the instances of such immeasurability of the human. In the program description, the curators invoke Moten’s idea when they ask “if anything is still left of the human, and how we might enact that remainder.” It is important to note though—as all three stressed when I corresponded with them via email—that Moten’s title was chosen after the program had been finalized. Rather than reflect Moten’s concepts, these films create productive reverberations between Moten’s vision of what he calls “the human remainder” and the programmers’ own ideas about the importance of human interconnectivity and of remembrance and archive preservation, as the basis for new beginnings.

The curators ask in the program notes, “Can remembrance fix a broken world?” At the core of this inquiry into the world, and the status of the human within its historical, sociopolitical, technological, and ecological parameters, lies the emphasis on feeling—feeling more than, but also less than.

The focal point of this year’s Flaherty NYC series seems to be Marie Menken’s Glimpse of the Garden (1957), showing in Program 2. As Devon Narine-Singh told me, quoting the experimental filmmaker Ephraim Asili, “All roads lead to Menken.” Narine-Singh stressed Menken’s foundational place in the history of American experimental cinema, as well as her influence on future generations, reflected today by the preservation efforts by the filmmaker M.M. Serra at the Film-Makers Cooperative, and by ongoing research. In Glimpse of the Garden, Menken focuses on a mundane stretch of a park. In place of a totalizing vision, she offers us a glimpse, or more precisely, a series of rapid, staggered glances of a park path, and, in extreme close-up, plants and flowers. On the film’s soundtrack, processed, sped-up bird and insect sounds attack our senses. Meanwhile, the camera’s spinning and jerky panning up draw our attention to the mechanics of seeing.

Menken embraced experimental film as an improvement on painting, though her films aren't necessarily painterly. Glimpse immerses us in mechanic “twitter,” as Menken liked to say—a conflation of biology and technology, which acquires a new slant in our social-media age. As “twitter” suggests, viewing Glimpse is far from calming. But a Mapplethorpian eroticism also comes to mind, particularly when viewing the zooms of flower helixes with their hairy armatures, the phallic stalks, so much more startling when abstracted from their surroundings, and the dark labial plant cores, with their expressive wetness, roughness, and wrinkles. In Menken, such deliberately hastened titillation is, however, also robotic. In the end, Menken’s film is more about our fractured, provisional understanding of the world, as made possible by seeing, as it is about nature, per se. At the same time, we never get a sense that nature is tamed, or made orderly in Glimpse; instead, to borrow a phrase from Moten, the “swarmed seriality of the mechanical buzz” releases the uncanny wonderment of the natural world. Entering it is like being an alien, discovering the Earth for the first time.

Most of the films in Flaherty NYC’s Program 1 correlate, in one way or another, with both the human remainder that so deeply interests Moten, and with Menken’s “twitter” aesthetics. M. Woods’s Bedford Cheese (2016) is perhaps the closest example. The film was shot in an apartment and in the streets, including in front of Brooklyn’s Bedford Cheese storefront, yet Woods’s extreme manipulation of the image makes it often seem as if it were all happening inside a corrupted video file, at the critical point of meltdown. At times, it’s possible to make out particular objects in the film, captured inside the apartment by the swooning camera: a television set, a bed strewn with torn, prurient magazine photographs, McDonald’s bags, and a pair of hands wearing plastic gloves—the camera glued to the body, creating a disorienting, claustrophobic point of view. When later a full figure appears in this setting, it has a spectral, de Kooning-like projection for its head. The accompanying text on the screen reads, “this is hell;).” At other times, garish blurbs of color streak down the frame, as if in an abstract-expressionist action painting. The film thus conveys a digitally construed existence, in which vision and reality become utterly degraded. The dirtied, infinitely excitable, subjectively undifferentiated visuality of Bedford Cheese at times manifests a psychotic state, an instance of a symbolic rupture.

Early in Bassem Saad’s Kink Retrograde (2019), a man wearing a white jumpsuit performs sun-salutations in a field bristling with wheat stalks. What looks like an industrial waste-disposal site is visible in the distance. This image then dissolves into molten, swaying brown shapes, whose multicolored rims resemble oil-stains. Single-line texts run across the screen, introducing the film’s context: a world no longer understood by scientists as capable of regaining an equilibrium, but instead, an emergence of “a new ‘resilience’ view” that presupposes “permanent management of shock, crash, and spillage.” Saad shot Kink Retrograde after researching the water crises in Beirut, but while some of the film’s images deal with this context explicitly—in one of them, the jumpsuit-clad “scientist-figure” pumps water with an edema from a green swampy puddle—others have a looser, quasi sci-fi feel. In one, two performers walk past each other against a purple-tinged city skyline; in another, a small group congregates in a vast, sandy landscape. In the voiceover, the narrator talks of the future’s resilient children, who will deem the social contract void, and create a one based on “pure kink.” In this section, Saad seems to address the programmers’ question of how the past—in this case, an outmoded approach to not only ecology but also sex—can form a basis for the future. Regardless of whether we take his idea of “pleasure and pain, at the end of the world” to be the Earth’s last apocalyptic gasp, or, instead, a new foundational ethics, Saad’s invention of a “risk-aware Consensual Kink” draws a striking contrast between the ecological risk that we are forced to engage in every day, without trust or agency, and the consensual risk involved in sexual play. More broadly, Saad takes the scarcity—the state of less than—as a basis for a futurist vision of an autoexcessive world.

Francois Knoetze’s hallucinatory Core Dump (2018) also takes toxicity and scarcity as the basis for a future insurgence. A young Senegalese man recounts in voiceover his slow mutation into a sentient robot. As with Saad’s film, Knoetze roots his in fact: one of the film’s archival clips mentions the high levels of lead discovered in the bloodstreams of a number of children in Dakar. Knoetze incorporates other archival material from Senegal’s history and footage of street life into this science-fiction tale. The protagonist’s body is said to have merged with the technological waste that he began refurbishing as a child—one scene enacts an electrical-surge fire, presumably responsible for his mutation. The actor’s mask and costume are an amalgam of electric wiring, synthetic casing, and “bleeding” flesh. The voiceover’s prophetic pronouncements about the future—“In the world for which I’m heading, I am endlessly creating myself”—clash with the imagery that stresses bodily mortification and reenforce a sense of hopelessness. Despite a foreseen future, in which the global technocrats surrender to the dispossessed mutants of their own creation—the West vanquished by its own technological debauchery—this message is dampened by the film’s visual insistence on the abject, which makes it harder to imagine how a future redemption of the violent past might emerge from a present marked by wounded precarity.

The insistence of Knoetze’s film on rooting the historical narrative in a singular subjectivity points us back to the postulate of feeling, feeling more, feeling more than, proposed by Moten. This idea is also tied to Moten’s consideration of marginality. “Can marginality be depoliticized?” Moten asks elsewhere in his book, suggesting that the question “proceeds from the assumption that politics, insofar as it is predicated upon the exclusion and regulation of difference, will have always been the scene of our degradation and never the scene of our redemption, redress, or repair.” Considering Core Dump through this lens, one might argue that itis a prime example of a “more than,” aka a reparative, redeeming gesture, in which the subject transcends his invisibility (see also Baldwin’s Invisible Man), and the brutal necessity, to articulate a vision of a future insurgence.

This sense of insurgent hope and of memory laying the groundwork for future possibilities is central to the Flaherty program—even in those films that might seem despairing, as Core Dump does. Among other films in Program 1, Wickerham & Lomax’s Whales SPF 50, takes a racist notion that Black Americans cannot float, and unravels it, by braiding in the voiceover multiple voices telling of experiences with swimming. Meanwhile, the images are a free-flowing mosaic of Black men posing against various backdrops, some real (a stream in a forest), others artificial (collaged marine-life computer imagery). Often the image itself has a watery effect, rippling and undulating, as if to stress the feeling of aquatic submersion, and the sense of porous undifferentiation that it instills. From the myth of Poseidon, to a mother “perform[ing] a Pietá” on the narrator after his first time swimming, the film is suffused with defiant, persisting recollections. These stories are grafted onto a broader communal experience (in one such thread, Hurricane Katrina gets a brief mention). Such grafting recalls Moten’s “glow and blur of the collective head’s collective embrace” that makes one forget one’s invisibility. In another sequence, the narrator takes the racist notion that Black people’s presence in the water “produced gravy, the soup of Black people’s melanin,” and flips it, by saying, “but that soup was really medicinal, a coagulating healing force.” Whales SPF 50 thus enacts rapturously the “less than” to “more than” movement by superseding objectifying ideas by a deeply subjective memory, to forge a more interconnected future.

***

Alia Ayman, wrote to me that she thought of the films in Program 2, including Leah Gilliam’s Now Pretend, Shirley Bruno’s An Excavation of Us, and Erica Sheu’s A Short History, as “at once haunting and reassuring—reassuring in the sense that they have not been lost and are able to make it into a future that is at once dystopic and brutal, while also bearing witness to the endurance of life against all odds.” In this sense, the programmers inscribe the films that present particular historical sociopolitical contexts into Mote’s idea of “more than,” to stress the way in which collective memory and archival preservation shape what kind of future we might be able and want to envision and make.

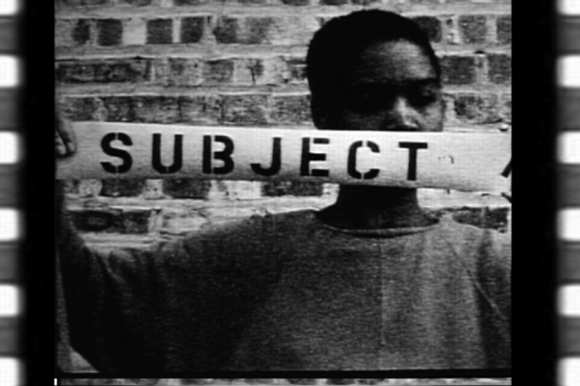

In Now Pretend (1991), Leah Gilliam takes the movement from object to subject, essential to Lacanian psychoanalysis, as her central metaphor. Gilliam then collages archival footage and personal memories into a grainy, black-and-white film whose frequent smudges and the shakiness of a handheld camera could be said to enact Moten’s experiential blur—moments hard to grasp or define. Gilliam oscillates between this rawer footage of streets, hallways, a figure glimpsed vaguely against background light, walking in a park with her back to us, or seen waist down, in the dark of a night, with scenes that are crispier and more frontal. In one, Gilliam faces the camera, while slowly unspooling a tape that reveals a series of binaries, e.g. “Object/Subject,” “Them/Us,” “Bad Hair/Good Hair,” “Ugly/Beautiful,” “Inferior/Sup….”

As in Wickerham & Lomax’s short, Gilliam fleshes out and calls into question oppositional constructs by including brief and varied anecdotal threads. The audio elements, for example, range from reading aloud fragments of Black Like Me (1961), a book written by the white writer John Howard Griffin, who tinted his skin to write about the embodied experience of segregation, to women who recall using yellow pillowcases as children to fake having blond hair, and other testimonies of un-reflexive, at times internalized racism. Some audio fragments speak to the hyper-awareness of cultural difference. For example, one woman confesses to feeling pressured to choose among her family’s “Jamaican English” and “Black English” or American English, depending on the social context she was in. In Now Pretend, both the psychoanalytic terminology and the social experiment devised by Griffin ring hollow when juxtaposed with the plurality of the Black experience in the 1960s. While Griffin articulates Blackness as a feeling of “less than” (the tint as a source of alienation from and a suppression of his “true” self), Gilliam works her way into this archival material and scientific terminology—into the slash that divides object/subject—to orient her viewers back to the immeasurable “more than” of the human.

Some of the recuperative gestures expressed in the Flaherty NYC program are more oblique. Hope may not be immediately apparent in the short film Ja’i huit ans (1961), by Yann Le Masson, Rene Vautier, and Olga Baïdar-Poliakoff. The film features children’s drawings that Franz Fanon collected during the Algerian War. The drawings portray tanks, soldiers, the torture and murder of the children’s families, but also the liberation fighters, resistance, and peace in vivid simplicity that inscribes trauma without resorting to graphic realism of wartime photography; they are accompanied by the voiceover, in which the children recall their war experiences. These wartime stories are preceded by quick still portraits, each of a different young boy looking straight at the camera, overlaid with the sounds of shootings and explosions. The encounters with the boys’ faces raise stark and infinitely complex questions. One would be hard-pressed to describe their effect, although the introductory text, which appears onscreen, prompts viewers “to think to that time when the Algerian people fought successful for their liberation against French colonialism,” and so suggests that we are looking at the children who inherited this future. But the encounters also bring to mind Judith Butler’s idea, from her essay, “Precarious Life,” that to really encounter a face is to “be awake to the precariousness of life itself,” which echoes the idea of the remainder: unmeasurable, beyond representation.

The remainder is also manifest in spiritual feeling. For example, in Vashti Harrison’s Field Notes (2014), the inhabitants of Trinidad and Tobago relate stories of jumbie (ghost) sightings and local beliefs about encountering ghosts —at times, with specific prohibitive warnings, spoken in the voiceover, and occasionally displayed on title cards (which also show field notes and maps), such as, “Never point at the cemetery otherwise a jumbie will follow you home.” The voiceover provides a historical perspective, with interviewees filling in the context of how ghost folklore betrays Spanish, French, and Creole influences, “some of the cultures brought from India and from Africa” during the colonial period, and thus tied to the history of slavery.

Although the film has some didactic elements, in a more playful gesture, the first image that Harrison presents is precisely of a hand extending from the camera’s point of view, pointing at the cemetery ground. One by one, Harrison then films the “haunted” sites—a cemetery, a silk-cotton tree, a home entrance (when not entered backwards). We may then say that Field Notes is both a cataloguing and a conjuring—a quest for rekindling the demonic, that which is less and yet more than human, within the confines of myths. While the film’s images construct a mundane diary of the islands’ flora, fauna, people, and homes, the voiceover creates a more horror feel, as if raconteurs have gathered by a fireplace to tell of humans attacked by demons. At one point, forest trees flickers, while we hear buzzards loudly on the soundtrack; all this visual and aural excess—Menken’s mechanical twitter—instills a sense of haunting.

Suneil Sangziri wrote to me that the film describes “creatures trapped between two worlds—the living and the dead,” and so “sits somewhere between feeling more than and feeling less than, finding ‘the places where the natural and supernatural collide’ [as per the director’s description], to reflect on the spiritual and anthropological.” This ghostly evocation aligns with Moten’s mentions of the spiritual world. And while the uncanny, technological pulsations of films such as Bedford Cheese, Kink Retrograde, or Core Dump make them seem far from the realm of mythical ghost stories, there is nevertheless a strong sense that even in these postmodernist films, within materialist junk, eco waste and technology-spawned psychoses, some human remainder nevertheless survives.