Mirror, Mirror

By Chris Shields

The Story of a Three Day Pass

Dir. Melvin Van Peebles, U.S., 1968, Janus Films

In Melvin Van Peebles’s groundbreaking 1968 film The Story of a Three Day Pass, newly restored and premiering in theaters this week, his protagonist, beaten and bloody, cries out, “I’m not a n----r! I’m a person, I’m a person!” It’s a gut-punch of a line, and one that, sadly, still resonates. Van Peebles, a radical artist and one of the key figures in 1970s Black Cinema, never shied away from these brutal realities and, indeed, his career itself embodied the desires, contradictions, concerns, and challenges African Americans faced—and continue to face. Van Peebles’s feature debut uses the possibilities opened by the New Wave (jump cuts, pop music, repetition) to explore something profound about race, identity, life, love, the world, and one’s place in it, and its rediscovery and restoration is an occasion for celebration.

After receiving a B.A. in literature from Ohio Wesleyan University and serving three years in the United States Air Force, Van Peebles worked as a cable car gripman in San Francisco.As he tells it, a passenger gave him the idea to start making films, and in 1957 he shot his first short film (Pickup Men for Herrick). Van Peebles took his short films to Hollywood, but, with Black directors relatively unheard of at the time, he found that only menial, low-level jobs were open to him. His films, however, gained the attention of Amos Vogel at Cinema 16, and this eventually led to an invitation to France from Henri Langlois, co-founder of the Cinémathèque Française. Van Peebles left for Europe, learned French, and wrote a series of novels in his new language, and after receiving a grant from the French government, the director shot The Story of a Three Day Pass, based on his own novel and his experiences in the United States Air Force, for $200,000 over a course of five weeks. After his debut feature film gained the attention of Columbia Pictures, Van Peebles returned to the United States and directed Watermelon Man, a subversive comedy about a racist, white insurance salesman who wakes up as a Black man. The film was a success, but rather than accepting the three-picture deal Columbia was offering, Van Peebles, wanting complete control of his next project, chose to make his independently produced and financed masterpiece, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, which would be a defining American film of the 1970s.

The Story of a Three Day Pass, adapted from Van Peebles’s French-language novel La permission (written after he discovered a law stating a French writer could obtain a director’s card to adapt their own work to the screen), follows a Black soldier, Turner (Guyanese-Born English actor Harry Baird), stationed in France and enjoying a three-day leave before he’s scheduled to return to base and start a new, higher position. From the outset, Turner’s leave is tainted by the racist, paternalistic browbeating of his commanding officer, who delivers a lengthy monologue (directly to camera) about “trust”; it’s a coded way of telling Turner, as the soldier explains it later, to be “a good negro.” A “good negro,” Turner says, is one his commanding offer can trust, “[...] to be obedient, cheerful, and frightened. Too frightened to go out with a white girl.”

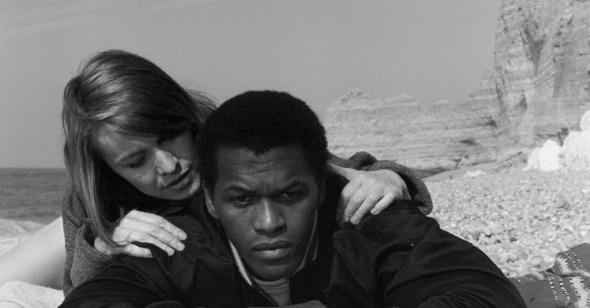

After arriving in Paris and doing some sightseeing set to fellow expat and jazz guitarist Mickey Baker’s driving, brassy score (like in Sweetback, music provides the formal backbone of the film), the soldier finds himself in a cozy nightspot, donning a fedora and wraparound shades, looking like a hipster on European holiday and on his way to breaking his commander’s unspoken dictum regarding “white girls.” Here, Van Peebles’s film breaks with not only formal conventions but also with reality, as the soldier glides—floats—across the room. He sidles up to the bar and orders une bière, scoping out the scene. He spots a young woman (Nicole Berger) at a table across the room. In slow motion, the crowd parts and the music swells, and in a moment prefiguring Scorsese’s 1973 Mean Streets, time stops for stylized cool. Importantly, however, when Turner eventually reaches the woman, his hat and shades fall to the floor, shattering his suave, protective persona and revealing the shy boyishness of the man underneath.

In moments like these, Van Peebles’s film uses the stylistic and formal innovations of the New Wave to brilliantly represent emotional and psychological interiority on screen. Earlier in the film, Turner confronts his image in the mirror, and his reflection talks back, accusing him of being an “Uncle Tom,” invoking the shadow side of Turner’s new opportunity, and triggering the self-doubt sowed by a lifetime of casual and systemic racism. These moments of vulnerability pervade the film—the mirror image becomes a recurring device—creating a complex portrait of self-doubt, frustration, anger, and fear. It is this intimate dimension that is most powerful in Van Peebles’s film, and creates in Turner a fully fleshed character, made up of desires and contradictions.

The Story of a Three Day Pass harnesses the unique abilities of cinema to unite the social, political, and the personal. In a key scene—which must have been shocking for the time—Turner and Miriam, the young woman from the nightclub, make love. Their embraces are intercut in flashes with footage of social unrest, war, violence, and the two lovers’ respective fantasies. For Miriam, a white woman, Turner is an African native, “taking” her as she lies on a jungle altar. For Turner, Miriam is an aristocratic lady awaiting him at a country estate. It’s a difficult scene, but such psychosexual frankness about race would appear again and again in Van Peebles’s films (graphically in Sweetback), earning him a reputation as an uncompromising and provocative artist.

Despite the rollicking score and formal exuberance, the overriding feeling of Van Peebles’s film is gentleness. After Turner and Miriam make love, they lie in the dark together, and the soldier whispers, “I love you.” The moment is so honest, so tender, and perfectly rendered that it’s as if we’ve spoken the words ourselves, to a new lover. It’s these delicate moments that make the film so achingly beautiful, but also as complex as the human heart. The Story of a Three Day Pass is a romance, but it’s not a fantasy, so in the end, Turner pays for his “transgression,” losing his promotion and earning the ire of his commanding officer. He sits alone in the barracks, his privileges gone, and his future bleak. As he looks in the mirror, his reflection smiles back mockingly and gloats, “I told you so.” Turner replies with two words, which, if you take a moment, you can probably guess. This moment of terse directness, in light of all the poetic beauty that has come before it, sums up Van Peebles’s film perfectly and gives a taste of the bold, unpredictable, subversive works to come.