David Fincher’s work, inclusive of his time in television advertising and music videos in the ’80s and ’90s, illustrates a director’s desire at first to uphold and then transcend the strictures of the camera itself.

Years in Review

One Battle After Another, It Was Just an Accident, Caught by the Tides, Afternoons of Solitude, The Secret Agent, Blue Moon, Peter Hujar's Day, Cloud, Misericordia, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl

Even if you get good at walking, the ragdoll physics on which the game is based will continue to plague you. They are deliberately imprecise, and there’s no guarantee that moving in a certain way will produce an identical outcome each time.

Sound of Falling anchors the undulations of history in a physical structure, a home inhabited by generations of people. That allows Schilinski to enter the past through oblique, almost surreptitious, methods, which casts history as a moving amalgamation of life’s minor and mirroring moments instead of dramatic apexes.

Magellan is one of the few films to cover this episode of the Age of Discovery, and Lav Diaz uses this stab at a grand seafaring spectacular to reject the idea that white colonialists “discovered” anything at all.

This is a very profoundly intimate, personal family story. So while certain dates are very important because of historical events, I wanted the 1970s to have less of that. I wanted for us to see a sense of normalcy with this family.

In the face of constant pro-AI propaganda, it is tempting to fall back on flimsy sentimentality. The romantic critic’s impulse is to wax poetic on some ineffably “human” quality to art.

Like late Ozu, with his parade of seasonally titled shomin-geki exploring the practically endless permutations of family life, Father Mother Sister Brother is a series of intergenerational vignettes.

Between its compositional dynamism and picaresque sensibility, the film is an auteur work to the core; it is also enervating in ways that do not so much undermine the stylistic pyrotechnics as indicate they’re the source of the problem.

Marty Supreme aims for something like grunge Barry Lyndon, a period picaresque epic about a sociopathic climber, but scrappy instead of stately, obnoxious instead of ironic. Yet beneath the grime it’s comparably handsome.

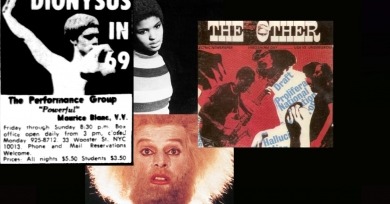

The new book from J. Hoberman traverses a wide swath of mediums and movements that, in his telling, coalesced into what we now recognize as the counterculture of the mid-to-late 1960s.

For this new symposium, we asked our contributors to pitch an idea for an essay centered around a film that somehow utilized or enabled a technology (relatively new or more widely available at the time of its making) that was indivisible from the experience, meaning, or aesthetics of the film itself.

Harnessing the imperfections in the digital cameras’ image-rendering capabilities and rudimentary audio fidelity, Godard confronts the crisis in neoliberalism, the ascendence of digital cinema, and the extinguished dreams of socialism and celluloid from the previous century.

It suggests a unique cinematic aspiration from a time before the film industry dedicated its energies almost entirely to narrative, and when the question of what was to become of cinema was undetermined.

For all our anxieties around the obsolescence of the medium, Bi Gan is moved by an unwavering belief in its subversive powers. Resurrection is not a valentine so much as a manifesto, a rousing wake-up call to all that cinema can still do.