The Killer Inside

Cure meets Se7en

by Travis MacKenzie Hoover

The fascination with serial killers, at least to the popular consciousness, lies in their complete adherence to self-created logic. Sane people are at the mercy of shifting values, competing viewpoints, and a general sense of semiotic vacillation; mass murderers invent a private universe of important concepts and amoral tenets that never waver and are utterly unchangeable. Against that constancy comes a sweep of mixed emotions from hatred to envy—a disgust at his refusal to accept the tenuous détente between individual need and unstable societal demands; or a jealousy that the bastard is imposing his own will in the ultimate way while everybody else plays by the variable rules. His presence at once clarifies and critiques the limits of society and makes him a subversive figure in more ways than one.

The nineties’ cycle of cop/killer symbiosis films underlines the impossibility of separating the love and hate in the public’s relationship with the archetype. On the one hand, The Silence of the Lambs’ Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter represent law and lawlessness and cannot cross sides; on the other, Lecter understands Starling’s plight better than the apparently lawful do, and he offers a self-created response to the demands of a society that doesn’t understand her. The application of the template depends on how society is defined: though two serial killers coming from two completely different cultures will reveal different limits and faults, the function of the killer will be the same, to show what we might lose and what we could possibly gain by giving in to the impulse to kill in creative and self-determined ways.

In one sense, David Fincher’s Se7en (1995) and Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure (1997) deal with completely different situations. The former deals with an America choking on a morally bankrupt individualism and a complete disconnect from community values; like some Paul Schrader vision of God’s Lonely Man, its protagonist, Detective William Somerset (Morgan Freeman), walks through a world of rampant indulgence and self-interest whose end product is a mass of atomized individuals casually inflicting suffering. The latter suggests a stifling Japan in which consensus values have taken over to the point of personal negation: its detective Takabe Kenichi encounters a society in which people take on other’s burdens to the point of self-annihilation and neglect. But the relative merits of these societies are dealt with in the same way: by a cop and a killer seeing eye to eye by seeing completely differently and calculating the distance between the two.

The first requirement of the subgenre is a cop experiencing disaffection from society. Somerset is spent from watching a nameless city experience moral decay, his position summed up when he asks a fellow officer if a child victim saw the deaths of her parents, and his colleague wonders why he would care. The fact that he’s retiring proves that he’d rather not acknowledge the society that takes the self-indulgent easy way out, and as his naïve new partner David Mills (Brad Pitt) points out, he’s dangerously close to acting alienated and uncaring to those who are alienated and uncaring. Conversely, Cure’s Takabe (Koji Yakusho), is reaching his wit’s end in shouldering the burden of his mentally ill wife, a microcosm of Japan’s consensus society, which thinks of others before itself. Though he silently accepts his fate, he’s reaching a breaking point—with a doctor late in the picture stating that he looks sicker than his wife.

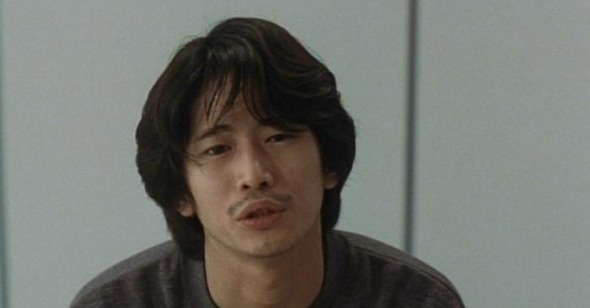

The films then explore the value of their disaffection by giving them a murderous projection of what they actually want. Somerset’s hatred of lax American morality finds its voice in John Doe (Kevin Spacey), who has his revenge on corrupt society by committing murders based on the seven deadly sins. Doe not only reflects the detective’s diehard moralism but also mirrors his erudition: Somerset matches the killer quote for quote as he rampages across the Bible, Shakespeare, and Milton with the lost values of culture inextricably linked with the lost values of community. Takabe, meanwhile, faces his wishful thinking in the form of Kunio Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), a homicidal Typhoid Mary who meets strangers, infiltrates their repressed desires, and releases them to kill some representative of that repression. True to pathological form, the detective becomes ever more agitated by his quarry because he knows that he wants to do the same.

When a director sends an emissary to do battle with his own fantasy scenario, it inevitably raises the question of that scenario’s validity. What are the consequences, for instance, of meting out revenge on people who help those who help themselves? For the most part, Se7en approves (however ambiguously) of John Doe’s mission of vengeance, particularly when he commits conjoined murders of a child molester and the lawyer who successfully defended him. Though this seems a bit extreme in terms of the lesser sins of gluttony (a morbidly obese man forced to eat until he bursts) and pride (a model found with her nose cut off “to spite her face”), the reality is that the seven sins are one: self-indulgence. Brush away the disappointingly conservative law-and-order platitudes and one finds a critique of American, if not Western individualism: that a society based on self-interest loses interest in the community and becomes a lawless frontier of the Wild West.

Similarly, Mamiya reveals the psychic fallout of Japan’s other-directed culture. Though all of his “victims” have no recollection of what they did or why they did it, they were clearly releasing repressed individual desires; in one instance, a cop murders a hated co-worker, and the serial inciter’s showstopper monologue has him revealing a female doctor’s wish to cut into a man. Where John Doe threatens the rules of his society by invoking community, Mamiya does it by invoking the self. Treating his subjects with a combination of Mesmer and Freud, he reaches into the subconscious individual obscured by the conscious adherence to the social contract. Mamiya himself has divested himself completely of external forms of identity, drawing in his prey with an appearance of being lost and without memory. He is a monster of the id, at war with the Japanese superego.

Thus the killer offers the choice between an accepted wisdom that holds too tight and an avant-garde anarchism that leaves destruction in its path, a choice that is no choice at all. And by hard-wiring us into the POV of an ambivalent policeman—someone trapped between protecting society and throwing in the towel—we see from the perspective of those who represent the battle we all face when cultural rules inadvertently step on basic desires for security and personal expression. Somerset vacillates between wanting to protect the right to act like an asshole and turning his back on the people who do so; Takabe ricochets between investing in his wife and ditching her, if not killing her. But the films also show that the choice is not quite the polarized matter it first appears. If Somerset becomes the hermit who hates society, he will be the callous individual he’s hated for so long; if Takabe gives in to his less noble urges, he will wind up violating the right of others to actualize theirs. Nothing is as simple as turning on and off a light, and thus Cure and Se7en offer a bad compromise between impossible alternatives.

Laying down any general principle is doomed to result in loose ends, unexamined premises, and bizarre contradictions, and the films end similarly unresolved. Se7en runs the quarrel between John Doe and Somerset aground on the consciousness of Mills, who in many ways is the person they both want to reach: Somerset wants to protect him from the dangerous world he doesn’t understand, while John Doe wants to rub it in his face. The argument hinges on what Mills will do when violated—in this case, presented with the severed head of his wife in Doe’s final coup-de-grace. The final brutal act demonstrates that Doe finds the original sin of self-indulgence within himself; though Somerset tries to keep Mills from exacting revenge on the killer, and thus proving his cynical view of human nature, Mills kills him, and removes all doubt. The two extremes change places: Doe loses by winning, and Somerset wins by losing.

Cure initially suggests that Takabe will take a middle path: instead of choosing one or another extreme, he will care for his wife from a distance, acknowledging her right to live in comfort as well as his right not to mortgage his happiness to do so. But the dichotomy rears its head in the issue of what to do with Mamiya. Having been half-mesmerized when questioning Mamiya, Takabe can be activated by his symbolic trigger (an “X” shape); when Mamiya escapes, Takabe tracks him down and kills him. But the detective sees the “X” in archival footage of mesmerism, and soon his wife turns up dead. Thus the major threat to society has been neutralized, but acts of resistance remain, the argument never finished, never answered, simply stalemated.

Se7en concludes with Somerset’s voiceover: “Ernest Hemingway once said, ‘The world is fine, and worth fighting for.’ I believe the second part.” It’s a pompous but effective way of summing up the cop-killer symbiosis. Social living is not fine, satisfying neither the individual nor the community but rejecting it is not an option. Whether it’s worth fighting for, our lives are a constant fight, requiring us to constantly reconsider the problem of what to do with ourselves lest some option be left unexamined. We can fall back on what we know, or we can acknowledge the killer inside us all, who knows what we need, whether we want to or not?