Make It Real, Make It Alive

Shonni Enelow on Listen to Me Marlon and Birdman

“What is documentary?” is perhaps less stimulating as an ontological question than as a phenomenological and historical one. How does something come to appear as a document rather than a fiction? What conditions make it possible to speak about a certain work as “documentary”? What work does the attribution of “documentary” do for a particular film? These questions tend to be addressed in light of the framing devices of authorship, the status of the historical, and what is often called “actuality” and the filmmaking techniques that produce the aesthetics of the real. This essay sets aside those concerns for another that is far less often addressed. Alongside the question of documentary, I argue, lies the question of acting.

What is acting? How do we know when someone is acting? How do we know when we are acting? What marks the boundary between acting and not-acting? How do we come to understand someone who is acting to seem to be not acting, or vice versa? If we can’t figure out who is acting and who isn’t, how can we speak of acting as an art? Is acting in fact not an art—just a particular psychological and social fact that some people are more disposed to than others? Or, to put it another way, if, as Marlon Brando asserts in Listen to Me Marlon, if “we’re all actors, all good actors” because “we all lie,” why are we sitting here watching a movie about the genius Marlon Brando?

These questions are of course germane to many of the most intriguing hybrid experiments in documentary going on today: Actress, for example, by director Robert Greene and actress Brandy Burre, intersperses clearly fictional scenes that assume the iconography of domestic melodrama in a documentary about an actress who plays to the camera with both emotional vulnerability and clear theatrical relish. The question that film, which follows Burre’s separation from her partner, raised for some critics was whether the fact that she seemed always to be acting meant that this was a film about a self-exploiting narcissist whose self-centeredness breaks up her family. The anxiety around whether or not Burre was acting slid seamlessly into a moralistic judgment about a woman not fulfilling her social role. Many of the responses to Actress demonstrated a cultural schizophrenia around women’s role-playing, role-playing that is presumed to be a necessary source of social stability and at the same time weaponized to invalidate their behavior.

I begin with Actress because that gendering of acting and the way it orients investigations into “fake” and “real” is of central importance to the two films that are my subjects here, Birdman and Listen to Me Marlon. The first is a fictional film about a fictional actor named Riggan Thomson played by Michael Keaton and the second is a documentary about a real actor named Marlon Brando, but the similarities between both the subject matter and the form of the two films are striking: both films are about white male American actors who, after experiencing early success, develop increasingly knotty relationships to their own fame as they age; both begin with voiceovers that announce their subjects’ divided psyches; both show us clips from hokey superhero movies the actors took part in; both include scenes with interviewers who in various ways “don’t get” the actors; both portray the actors’ technological fantasies of immortality; both foreground the actors’ failures as fathers to wayward daughters; both include fatal or near-fatal shootings to punctuate “the real.” Both include lengthy shots of cluttered, trash-strewn rooms. Both foreground jazz percussion. Both even include full performances of the same Shakespearean soliloquy: “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow and…” from Macbeth.

What is going on here? We’re clearly in the presence of a powerful mythos. And I’ve saved the most important similarity for last: in both films, the actor or actors (in Birdman, both male leads, Keaton’s Thomson and Edward Norton’s Mike Shiner, fit this bill) are obsessed with “the truth,” “the real”; acting is about honesty, nakedness, reality. “Thank you for an honest performance,” is the message written on a cocktail napkin from Raymond Carver that supposedly catapulted a young Riggan into acting; “Does anybody give a shit about truth other than me?” Shiner yells at one point; “Make it real, make it alive, make it tangible,” Marlon says, as the documentary shows us clips of him apparently doing just that. Birdman makes fun of this obsession (its self-reflexivity was much lauded), and in the end pushes it to an absurd, if superficially logical, extreme: Riggan actually shoots himself with a real gun onstage, and is rewarded with a review in the New York Times that applauds the play’s “superrealism,” “the blood that has been sorely missing from the American theater.” This is not a particularly original joke (artist Chris Burden had someone shoot him with a gun for his 1971 performance “Shoot”), but it instructively reveals the film’s investment, above and beyond its irony, in the values it pretends to undercut: Riggan’s play succeeds, and his personal life is righted, because he really meant what he was saying on stage. Like the film’s single-take aesthetic, a technical feat meant to foreground the wholeness and continuity of its constructed reality, as the film presents it (Riggan’s quivering voice speaking those final lines with surprise and hushed awe) the fact that Riggan shot himself with a real gun was part and parcel of the emotional genuineness of that final performance.

We often speak and write as if words like “honest,” “authentic,” and “real” were transhistorical categories, sometimes even in spite of ourselves, but if the history of performance tells us nothing else, it reveals they’re profoundly contextual and relative. What looks or sounds authentic and real to someone will seem fake or contrived to someone else. This is a problem when it comes to talking about acting: not only is it very difficult to isolate the formal elements of a performance, but it’s also very difficult to isolate what makes a particular performance or performer look or feel better or even different from another without getting into extremely complex cultural codes and idioms. So discussions about acting often come down to vague phrases and “gut feelings,” which you don’t need to be Roland Barthes (the object of a blithely homophobic anti-intellectual jab in Birdman) to know is a good indicator of entrenched ideology. This doesn’t mean that we can or should dispense with these categories, or pretend they don’t hold purchase. But it does mean that it’s important to examine how they operate: what positions and assumptions they depend on or occlude, and who gains from them at whose expense.

Until now I’ve compared the films as if they were two coterminous versions of the same myth, but of course they aren’t. One is about the person who originated the myth itself, or at least gave it the particular characteristics that come to us in Birdman. Whether the film knows it or not, the characters of Birdman want to be Brando. Brando is the template for their masculine realness, Brando’s Method acting, the credit for which Listen to Me Marlon gives to Stella Adler, which is fair, but doesn’t really get at the combination of cultural and historical factors that led to a particular methodology of acting becoming so hegemonic that it actually looks to many people like the only kind of good acting there is. What that methodology specifically includes is less important than what it claims to be able to accomplish: the revelation of universal truths about humanity. As Brando in voiceover asserts in Listen to Me Marlon, before Stella, before Marlon, all acting was wooden, cookie-cutter; all actors played the same role over and over, with canned melodramatic gestures. This was a central part of the ideology of American Method acting, which developed techniques, based on the work of Russian theater director Constantin Stanislavsky, to bring together the lived experience of the actor with the fictional experience of the character. However, it doesn’t take away from Brando’s brilliance (or Geraldine Page’s, or William Greaves’s, to name two other artists influenced by Stanislavsky) to point out that these claims—that all acting was terrible until one great actor came along and changed everything—recur regularly in modern theater history, at least since David Garrick, whose acting eighteenth-century theatergoers found breathtakingly lifelike. Scholar Sharon Marcus has referred to this phenomenon as “the realist moment”: when a new form of acting comes along with a charismatic personality attached, it makes the older forms look artificial in contrast. In fact, given this history, what’s surprising is that the myth of Brando’s timeless genius has endured this long—it probably has a lot to do with the baby boomers and the continued fetishization of the American midcentury, also on view in Birdman, both semi-ironically through Riggan’s attachment to Raymond Carver and unironically in its jazz score. In the first shots of Listen to Me Marlon, we watch Brando’s digitized head float in space as he muses that in the future all actors will be computer-generated: “Maybe this is the swansong for all of us,” he says. Perhaps in hindsight we’ll see that Birdman was the swansong for the myth of the Great Man of American acting.

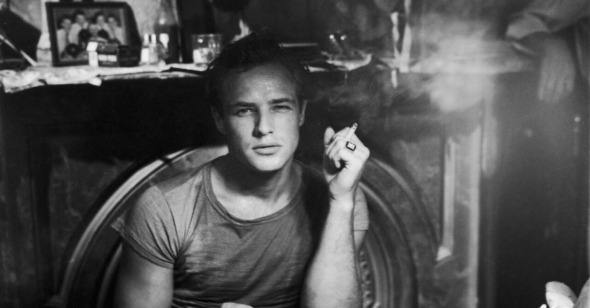

Fairly or unfairly, a lot of what came to be understood as Brando’s persona actually has to do with one particular character he played, Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire. Insofar as Brando’s acting presented a new model of American masculinity, it was partially based on the emotionally explosive, sexually violent Stanley. Brando-as-Stanley is what Norton’s Mike Shiner (presented as the authentic theater actor, the critical darling) is really doing in Birdman: throwing the set pieces around, attempting to rape his girlfriend—these are Stanley Kowalski maneuvers, an actor doing Stanley as if Stanley were himself an actor, an actor superficially like Marlon Brando (disdainful of Hollywood, disruptive to productions). Tennessee Williams’s Streetcar is to some extent about the violent masculinism behind the apparently neutral idea of “reality”; I’d like to say Birdman recognized this too, and I had some hope when, after he tried to rape her onstage, his girlfriend Lesley Truman, played by Naomi Watts, furiously left him, but her rage is massively undercut when another actress, Laura Auburn (Andrea Riseborough), calls Shiner’s behavior “kinda hot,” and in the end, he still gets to be deep and sensitive and make out with Emma Stone. (Lesley, in contrast, gets a condescending sob-fest in which she wails, “Why don’t I have any self-respect?”—which I’m pretty sure is the wrong question—and, even worse, is answered by Laura, “You’re an actress, honey.” Ah yes, those insecure, self-respectless actresses.) Streetcar made us see the ethical nightmare of Stanley’s attractiveness; Birdman makes it cuddly.

But what about the other, stranger similarities between Birdman and Listen to Me Marlon—that jazz percussion, for instance, or the failures of fatherhood, or that verse from Macbeth? I’m cheating a little bit with jazz percussion, which plays a much larger role in Birdman, scoring almost the entire film; in Listen to Me Marlon, it appears in a photograph of Marlon playing a drum and the mention of his nights in “the black part of town” (which the filmmakers unhelpfully illustrate with a photograph of black people dancing). Nonetheless, I think it’s important, because Listen spends so much time on Brando’s various identifications with people of color: his speeches for the Black Panther Party, his famous activism for the American Indian Movement, his fascination with Tahiti. A fuller picture in a smarter film would have shown us the complexities at play here: on the one hand, it’s crucial to recognize the imperialism of the fantasies of authenticity he attaches to Tahitians, and it’s likewise important to understand the ways his American Indian activism dovetails with longstanding white American fantasies about the authenticity of Indians (fantasies constructed at the very moment of genocide; for instance, in one of the most famous theater productions of the nineteenth century, the American actor Edwin Forrest’s performance of Metamora, “the last of the Wampanoags” –– a performance that also cemented the association of American acting with muscular, unschooled masculinity, prefiguring Brando’s Stanley Kowalski). In Listen, people of color are abstractions. On the other hand, Brando, explicitly in his AIM activism and perhaps in Civil Rights work, apparently recognized the problems with his own iconization in the movements, and certainly recognized the role of the culture industry in perpetuating racism. Birdman, unsurprisingly, doesn’t give us any of these complexities either, content to use the percussive score and the surprise appearances of the black drummer as lightly retro panache that also, like Listen’s “black part of town,” trades on the “realness” of black people.

The trope of failed fatherhood is part of the drawn-out mortification of the actor that gives both films their vague Christ narratives (revelation, degradation, transcendence): the actor, who is supposed to personify our collective anxieties—about aging, about being loved, about our own significance in a changing world—suffers for our sins. Of course, the story of Brando’s children, at least of the two (of sixteen) the film includes, Christian and Cheyenne, is truly tragic (Christian was convicted of killing Cheyenne’s boyfriend; Cheyenne killed herself soon after), which is why it’s upsetting to watch the film exploit it with sentimental images of their childhood. In Birdman, Riggan’s daughter, Sam (Emma Stone), is at first a disruptively cynical presence in the film—she gets an angry monologue in which she calls out Riggan’s search for authenticity, which, she perceives, is really about validating his own ego—but even her anger is tamed, as is Riggan’s ex-wife, played by Amy Ryan, by Riggan’s final sacrificial gesture.

And Shakespeare? What is it about that particular soliloquy? Shakespeare often used the trope of the theatrum mundi, the theater of the world, in his plays, and this soliloquy is among the most famous examples:

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

The key themes of both films appear here: mortality (personal and historical: there’s an apocalyptic strain in both, as there is in “the last syllable of recorded time”), the foolishness and vanity of human activity, cast as the actor who “struts and frets.” But, as always, it’s worth emphasizing the context. This soliloquy comes from Macbeth: Macbeth delivers it after hearing about the death of Lady Macbeth, his one ally during his murderous ascent to power. Those stepped on during that ascent have the right to wonder. It is hard to be alone with the full weight of your guilt, isn’t it? But do we really have to mourn for you, too?