For many of us—and presumably everyone who writes for Reverse Shot—the last twelve months would have been unimaginable without movies. And while we often took refuge in the familiar and the long-beloved, keeping up with new films was, at times, even more comforting—a reminder that the art form is alive and healthy despite the onslaught of corporate monopolizing and the streaming dominance that made the closing of movie theaters feel even more ominous. An intrinsic truth hasn’t changed, and likely will not: artists are out there making movies. Seek out their work.

Given this, we dove into our annual activity with little hesitation: the making of the list of the year’s best films, determined by polling our major contributors from the past year. Still, we thought the unorthodox nature of the year called for a slight change in the rules. The landscape of movie watching is ever-shifting, and this year there were tectonic slides; for instance, anyone from anywhere in the U.S.could have ostensibly watched any film from NYFF, not just privileged New York moviegoers. So, in addition to movies that received official distribution in 2020, whether online or theatrically, we allowed our critics to vote for films that premiered at festivals over the course of the year. How this affects our future list-making endeavors we’ll have to see, but for now it feels right. Our number one movie, for instance, seems like the perfect film for 2020, a film about isolation, union, and catharsis.

[Capsules below written by Edo Choi, Jordan Cronk, Caden Mark Gardner, Susannah Gruder, Eric Hynes, Michael Koresky, Chloe Lizotte, Jeff Reichert, Imogen Sara Smith, Kelli Weston, and Chris Wisniewski.]

1. Days

Perhaps it’s no surprise that a new film by Tsai Ming-liang would resonate in a year of physical threat and psychological alienation. Yet there’s more to the profound way that Days, Tsai’s first narrative without a pre-scripted concept, alchemizes minimalism into corporeal maximalism. For the striking, stoic Anong Houngheuangsy, a Laotian migrant living in Thailand (where Tsai, after a video chat, flew to film the transfixing way he prepared his food), it’s a reflection of ordinary routine; for eternal Tsai presence Lee Kang-sheng, it’s a parallel narrative of taxing medical treatment. After more than 30 years in front of Tsai’s camera, and alongside the younger Anong, Lee now imparts a visually evident wear to match his melancholy: lines of age emerging on his face; painful burns sustained from on-screen moxibustion treatment for the actor’s chronic illness. So when both characters come together, it creates an unusually pure escape from solitude and bodily breakdown—but only within the finite bounds of this twenty-minute sequence. “Our bodies are like containers,” Tsai once said. “They hold material things like water, but also desire and feelings, and power too.” As we watch, hyperaware of our own containers, Days is radically physical, situating a fragile body as a universal experience and an isolated vessel. —CL

2. Martin Eden

Pietro Marcello’s Martin Eden is many things: a sweeping and cinematic künstlerroman; a grand historical epic deeply concerned with class struggle and revolution; an experimental work that dislocates the complacency of period filmmaking through deployment of anachronism and archival imagery (found and faked) while functioning as a work of narrative art. But Martin Eden also seems to be, crucially in this moment, a dissection of the mechanisms by which a certain type of media creature is formed, elevated, and then inexorably routed down the road to curdled self-parody. Young Martin looks around at his life and sees the ills of capitalism everywhere. Finding no answers in the tepid liberalism or blinkered socialism of his day, and spurred by rejection of the genius he is sure he possesses, he turns towards a performative individualism that only renders him more popular and beloved. (These types of personalities have proven sadly compelling through the ages: the Jack London novel upon which Marcello’s film is based was apparently intended as a critique of its protagonist but was widely misinterpreted as roman à clef.) Martin may be a fictional creation, but his carbon copies are everywhere: Jordan Peterson, the Hillbilly Elegy dude, Fox News’ evening lineup. It’s a testament to Marcello’s filmmaking brio and Luca Marinelli’s gutty lead performance that Martin Eden remains an exuberant watch even as its protagonist craters into ugliness and the world descends into war. —JR

3. Time

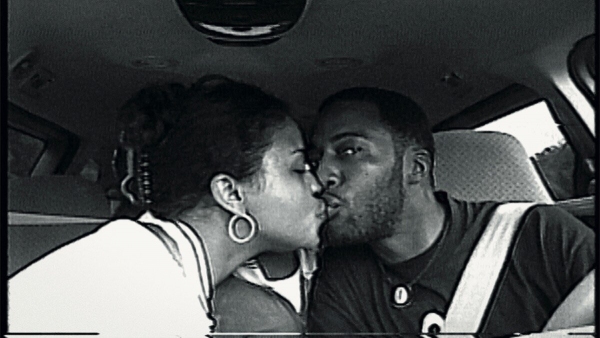

Much of the poetry that animates Garrett Bradley’s Time is organized around absence. The film follows the wonderfully charismatic Fox Rich (born Sibil Fox Richardson)—activist, entrepreneur, and mother of six—as she fights for the parole of her husband, Rob, serving a 60-year prison sentence at the Louisiana State Penitentiary. Where other carceral nonfiction often concerns itself with the details of the crime, pervasive institutional corruption, or, revealingly, innocence (those who do not “deserve” confinement), Time attends to humanity, which is to say all the banal milestones—the moments—that are lost to the incarcerated and those who love them. Nearly two decades of home videos recorded by Fox and her children form a heartfelt archive of such missed moments, exquisitely curated by Bradley, who intertwines this footage with the present, all in black-and-white, captured by three cinematographers. The result is a rhapsodic portrait of the glorious mundane that forces audiences to confront how profoundly the criminal justice system disrupts the intimate lives of the Black families disproportionately touched by it. Time would already be among the era’s most formidable works, but then comes its crowning jewel: a fleeting, fairytale-like sequence in a car, an episode of divine relief, and a testament to the art we don’t see, off-camera, that the filmmaker forges with her subjects. —KW

4. I Was at Home, But…

Angela Schanelec’s ninth feature and first to be distributed in the U.S., I Was at Home, But… is a rare object: a breakthrough achieved on its own unique terms. Never one to compromise, the German director has charted a singular quarter-century path through contemporary European art cinema, pushing with her latest ever further from the Berlin School movement with which she was once grouped. While still geographically localized, Schanelec’s work has become increasingly untethered from the bounds of concrete realism, leaping instead across spatial and temporal chasms unavailable to the more earthbound arts. Reflecting its Ozu-esque title, I Was at Home, But… is made up of equal parts rigor and warmth, an uncommonly fluid articulation of oft-opposed elements. In its elliptical telling of a single mother of two (Maren Eggert) grieving the loss of her husband, the film forges a dialectic of growth and experiential understanding through a tragedy of unremarked-upon but deeply felt significance. With typical economy, Schanelec structures the narrative as a series of rests and subtle grace notes, its musical form finding full expression in perhaps the year’s most indelible combination of sound and image: Eggert’s character, lying prone at the foot of her husband’s grave, accompanied on the soundtrack by the mournful piano and acoustic guitar interplay of M. Ward’s cover of David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance.” Like the trembling flower and serious moonlight detailed in Bowie’s hit single, I Was at Home, But… is a film of stark, unforgettable moments of extra-sensory storytelling. —JC

5. Bacurau

Set in the indeterminate near-future in and around a fictional Brazilian small town, Bacurau opens unsettlingly, with a water truck speeding down a road past a vehicle filled with coffins. Within minutes, co-directors Kleber Mendonça Filho (Aquarius) and Juliano Dornelles (a filmmaker who served as production designer on Mendonça Filho’s previous directorial efforts) abruptly shift the tone with the warm homecoming of Teresa (Barbara Colon). She’s arrived for her grandmother’s funeral, a community-wide tribute turned spectacle when the alcoholic local doctor (a steely and world-weary Sonia Braga) takes the opportunity to air her grievances toward the deceased. As it moves from apocalyptic road movie to a rich celebration of community love and loss to the melodrama of Braga’s outburst, Bacurau makes clear its intention to keep viewers on their toes. But death hangs over the film from the beginning. More ominous portents begin to pile up—bullet holes in the water truck, mysterious saucer-like drones, dropped phone lines, the literal disappearance of Bacurau from online maps. They’re harbingers of the provocative, wild, ultra-violent mash-up of Cinema Novo, spaghetti western, and Tarantino-style revenge fantasy. This genre-bending B-movie clothed as aesthetically bold international art cinema—or is it the other way around?—may have been the movie we needed most in 2020. A scathing critique of predatory whiteness and a ferocious depiction of indigenous strength, Bacurau is a thrilling movie to watch, an exquisitely made piece of cinema, and a deeply satisfying political allegory that functions as both a deft genre exercise and a wholly original vision. —CW

6. Vitalina Varela

Vitalina Varela is the portrait of a woman, created by director Pedro Costa in collaboration with the subject herself, a nonprofessional dramatizing her own story of arriving in Lisbon from Cape Verde after the death of her husband, who abandoned her decades earlier to emigrate. From the moment her bare foot presses the ground as she steps off an airplane, Varela commands the screen with elemental force and the depth of ambivalent feeling behind her sorrowful mask. As much as it centers Varela’s monumental presence, the film also revolves around absence. The house where she takes up residence is haunted, not by her husband’s ghost but by her unresolved feelings of anger, bitterness, and grief. Vitalina Varela is equally the portrait of a place, a hushed netherworld of narrow alleys, cave-like chapels, and crumbling shacks, their walls stained by migrants’ exhaustion and sadness. The film’s somber mood and funereal pace are pierced by beauty: scenes are carved out of blackness by raking light, saturated with unearthly intensity. When the image fleetingly opens out into space and light, these moments bring gasps of relief, like emerging into the air again after being buried alive. —ISS

7. Never Rarely Sometimes Always

The emotional crescendo at the heart of Eliza Hittman’s Never Rarely Sometimes Always catches you off-guard. Over the course of one painfully realistic scene, which fully immerses audiences in the vulnerable experience of being at a women’s clinic with a balance of sterility and sympathy, a nurse at Planned Parenthood slowly and methodically questions 17-year-old Autumn (Sidney Flanigan, in her film debut). Joined by her cousin Skylar (Talia Ryder), Autumn has traveled to New York City from Pennsylvania, where it’s illegal for minors to receive an abortion without parental consent. The nurse asks Autumn questions about her sex life, giving her the option to respond with never, rarely, sometimes, or always. As the questions become less and less innocuous, Autumn’s answers undermine the stoicism she’s fought to maintain, and we realize that her pregnancy is the result of unhealthy relationships with both her boyfriend and her family, with Autumn alluding to abuse in the latter case. The film situates this episode within a series of struggles the two girls undergo together, both subtle and stark—from unwanted advances from coworkers and fellow travelers on the Greyhound Bus to the countless logistical and emotional roadblocks they face leading up to the procedure itself. As in It Felt Like Love and Beach Rats, Hittman again demonstrates her acuity for capturing the ephemeral and ubiquitous hardships of youth, this time zeroing in on the lack of guidance and the unnecessary obstacles young women are made to face in taking control of their own bodies.—SG

8. Lovers Rock

Throughout his Small Axe series, Steve McQueen’s characters, from London’s West Indian diaspora, are consistently antagonized by the racist and paternalistic British state, whether by the police, white nationalist neighbors, or seemingly altruistic, ultimately ineffective governmental systems. Lovers Rock stands out for being a respite from this; it’s a film whose characters carve out their own spaces to experience a community and personal euphoria so often taken for granted by so many of us. The film’s house party casts an intoxicating, sensual, rich spell on the dance floor, with needle drops of Carl Douglas' "Kung Fu Fighting" to Janet Kay's “Silly Games", a song that recurs throughout the festivities. The interpersonal relationships of many characters, ranging from established bonds to budding romances, are fully realized thanks to the attention McQueen and his cinematographer Shabier Kirchner pay to the faces and body language of this ensemble, reminiscent of the work of Jonathan Demme and Claire Denis (whose U.S. Go Home feels like an older French sibling to this film). At once seemingly without a plot and yet so in control of mood, Lovers Rock is a cinematic tapestry of celebration and possibility. —CMG

9. First Cow

The films of Kelly Reichardt have an exquisite sense of scale. They don’t strain against the frame, they aren’t emblazoned with self-regarding gestures of ambition, nor do they make acts of restraint their own self-regarding gestures of ambition (the immodesty of performed modesty); they are specific, apportioned, aesthetically distinctive, uniquely realized. And Reichardt often animates these qualities in her narratives. In First Cow, we’re made proximate to a relationship that develops before us, its appeal and mutual value evident and manifest. As appealingly, un-fussily played by John Magaro and Orion Lee, Cookie and King Lu are motivated not by secret motivations but warmth, security, enjoyment of company, and collaborative advancement. These are men we’ve never met before on screen, with a rapport that’s both undeniable and irreducible, born of and limited by their time and place but never dehumanized by the space offered to them by the film. There’s an economy articulated in the narrative—one that’s wrapped up in the supply and demand of cow’s milk and oily cakes—and another defined by Reichert’s overarching balance of action, particularly laborious action, and free-floating wry humor, of demarcated dramatic space and evocative tactility. In First Cow, the domestic sweeping of a hut’s floor is a feat of cinema—meaningful, pleasing, moving—while never bothering itself or us with pretensions of being a feat of anything at all. —EH

10. Malmkrog [tie]

As we enter the third decade of the woebegone 21st century, I can think of no better overarching theme for a movie than the purgatory of discourse. Cristi Puiu doesn’t aim to make it easy on his viewers with the claustrophobic Malmkrog, in which a party of five Francophone Russian aristocrats pass one long day’s journey into moral twilight debating evil, war, and theology in a snowbound Transylvanian manse, but in a culture that has replaced the hope for epiphany with the expectation of toxicity, why should he? Puiu has made a film that's statelier than Buñuel, angrier than Oliveira, scarier than Rivette—in outline it's a “tough sit,” though it’s easy to surrender body and soullessness to its compelling portrayal of blinkered bourgeoisie and tail-swallowing belief systems; Malmkrog doesn’t “invite” viewers in, keeping us shivering, bitter-cold outsiders. Odds are it’s unimportant to you that its foundational text is Three Conversations About War, Progress, and the End of History, the same 1899 writings by Russian philosopher, poet, and theologian Vladimir Solovyov that inspired Puiu’s experiment Three Interpretation Exercises and which espouses theories of mass resurrection—perhaps the key to unlocking its most surprising narrative gambit. While this may sound purposely arcane to most of us, contemporary viewers accustomed to the digressive moral labyrinths of their social feeds may find themselves getting pleasantly lost in the intellectual pursuits of the privileged few who did little to staunch the unceasing flow of blood that would define the 20th century.—MK

10. To the Ends of the Earth [tie]

Like many young people of a certain temperament, Yoko (Atsuko Maeda) is a muddled soul yearning to sing from the hilltops, but inhibited by diffidence and detachment. Far afield in Uzbekistan as the host of a Japanese travel show, beleaguered by culture shock and men, she’s a familiar type holding the center of what would typically be a reassuring scenario for a movie. From this film’s first ghostly image—human silhouettes half-revealed through a doorframe—one senses something else afoot, however, stranger and altogether more unsettling than a routine comedy on the banal disappointments of modern tourism. A sly magician of space, Kiyoshi Kurosawa pinpoints Yoko’s malaise with finely tuned precision and gradually screwed tension in the shifting relationship between the character’s constantly offset figure and her alternately wondrous and threatening surroundings. Suggestive of The Wind Will Carry Us by way of Jacques Tourneur, his film builds toward a haunting centerpiece, one of the year’s true revelations, where the plunge into alien landscapes breaches the terrifying frontier of the unformed self. —EC