I Am the City

Ina Archer on Medicine for Melancholy

This column features essays about films made in the twenty-first century that deal explicitly or implicitly with matters of American identity.

Jo’: This is a one-night stand.

Micah: It’s only been one night, can’t do nothing about that. It is what it is.

Barry Jenkins’s first feature, Medicine for Melancholy, begins in media res as a young black couple—or a couple of strangers, as their discomfiture suggests—arise, each in turn silently giving their teeth a finger brushing. Together, they tiptoe over barely seen sleeping bodies. A telltale shot of assorted empty bottles and cans confirms a night of revelry. In concert, they slip out of the luxe glass and metal multiplex of the party space into a punishing San Francisco morning sun. His first words to her: “I’m sorry…hungover.” Her first words to him, offering panacea in a small box: “Medicine cabinet.”

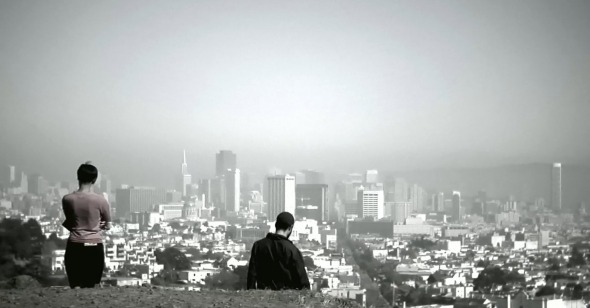

He leads her to a café that’s not far, “in Noe,” thus beginning a cataloging of Bay area neighborhoods that will subtly create an underlying mapping of the city. The photography by James Laxton is desaturated almost to shades of grey and white, with a residue of color that makes the matching pink hues of their t-shirt pulse, linking them as they ascend up and over a hill that reveals a vista of the city.

As they share breakfast, it is difficult to tell which is more painful: their hangovers or his futile attempts to otherwise get acquainted with her, blocked as he is by her terse responses. Admitting that they skipped introductions, she gives him the name Angela; he is Micah. He continues to stumble on, confusing who she may be with how she makes money (“Where do I work or what do I do?” she sighs). Like the place names and the ebbing color, the nexus of how and where rent gets paid will be a recurring motif in the film. Jobless, she is “making her way.” Micah insists on sharing a cab to her home, the direction to which she indicates with a dismissive wave of her arm. Arriving at a corner, Angela flees her erstwhile partner in transgression, not heeding his calls. The wallet that she leaves behind instead of a glass slipper will reveal that her name is Joanne. This intriguing pre-credit sequence ends with Micah alone in the taxi, unwittingly beginning the next 24 hours that we will spend with them.

Medicine for Melancholy, which received a 2008 Independent Spirit Award nomination for Best First Feature, stands out as both a “first” of its kind and as a disciple of earlier duet films like Before Sunrise (1995) or even Something Good Negro Kiss (1898), the newly uncovered film fragment of a Black couple (vaudevillians Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown) playfully canoodling. It is a quiet but influential work in its depiction of blackness, of Black romance and alterity in a shifting urban landscape. The film is both elegiac and symbolic, yet precisely located in San Francisco and true to the early 2000s—the beginning of the diversifying representation of Black lifeworlds that was ignited—underlined—by the Obama candidacy. A 2009 article by Dennis Lim quotes Jenkins, who said he wrote the film two years “before Obamania took off.” Obama opened up the representational arts to the notion that American identity is complex and situated and that it could be read through the experiences of the (Black) people right next door.

Medicine for Melancholy is the work that introduced Barry Jenkins to a wider public after being a part of the film community as a programmer and in other roles with the Telluride Film Festival for over ten years. When I first saw the film, the San Francisco setting was a place that I knew mostly from Hitchcock’s rear screens, tense noirs, disaster films with vintage special effects and comedies, memorably What’s Up, Doc? Revisiting the film during quarantine, now that I’m older and having spent six weeks close to the city itself, I recognize that my perception of the film and its setting, and how enthralled I was when I first saw it, have shifted. It feels slight, ephemeral and yet memorable, a romantic fantasy, easy to recast like a one-night stand.

In his poetic, analytical chapter on the film in his book Film Blackness (“Black Maybe: Medicine for Melancholy, Place and Quiet Becoming”), Michael Gillespie writes of the hues of the cinematography: “This unfixed filtering obliges the film’s sustained speculation on racial scripts and connotes the design of a fantasy.” The notion that Melancholy is a cinematic imaginary—and specifically Micah’s projection onto Angela/Jo’—appeals to me more in recent viewings. Initially, the visual language of Melancholy seems borrowed from documentary with the nearly black-and-while palette, the focus on youth, and sporadic sound and music cues recalling the streetwise mise-en-scène of the Nouvelle Vague. Stylistically, it shares many New Wave tropes, like the Jean Seberg pixie haircut that Jo’ wears, her love of film (shown on her MySpace page!), the elliptical editing, and a playful interweaving of romance and political discourse.

The film is a paean to the two actors—Wyatt Cenac’s protruding sloe eyes, charm, and gentleness prevail even during his needling, intoxicated confrontations with Jo’, behaving, as Gillespie says, like “drunken assholes in the street who think they know you.” Tracey Heggins’s enigmatic Jo’ is a cipher; her serene, egg-shaped head is as beautiful and inscrutable as a Brancusi bronze or the smooth mien of a Simone Leigh ceramic bust. Her refusal to be “fixed” racially by Micah is further suggested by her T-shirt designs, which feature surnames of female directors. First she wears a mauve-ish “Guy-Blaché” shirt (the French director Alice Guy-Blaché was the first woman to make a black-cast movie, 1912’s A Fool and His Money), and later she wears a pale yellow tee with “Loden” on it, referring to Barbara Loden, the director and star of Wanda (1970), a film about a woman whose life is defined by patriarchal restrictions by a filmmaker whose career was shaped by her husband, Elia Kazan. Like Wanda, Angela/Jo’ is a projection. Micah never asks her for details—where she is transplanted from, how long ago or who her people are. Yet he takes care of her while gently insisting on changing her.

They move through a city that seems to be an empty canvas on which they sketch out time together. The people they encounter are in the background, sometimes merely muted voices. The two share the insularity of lovers in close sync, as they drift through a museum and engage with monuments devoted to African American history. Later, they remain in accord talking and cooking in Micah’s apartment. Each serenades the other with guitars, first Micah sings “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” at her boyfriend’s place, and she reciprocates by offering to play a song for him in his tiny apartment, leading to caresses. They flirtatiously debate musical performances like comparing Rick James and MC Hammer music videos. Anticipating Moonlight’s exquisite mixing of Nicholas Britell’s compositions, evocative of 19th-century chamber works, with 1970s reggae (“Every Nigger Is a Star”) and contemporary remixes like Jidenna’s “Classic Man,” Melancholy is laced with an unexpected indie soundtrack. Moody song lyrics narrate their sexual intimacy: “Is this a dream, spending the night with you” from “Through the Backyard” by Au Revoir Simone. Alternative music street credibility is suggested by the artists and band names: Ivana XL, or Casiotone for the Painfully Alone. Strikingly, Jenkins floods the couple’s afternoon carousel ride with Dickon Hinchliffe’s haunting composition “Le Rallye,” recognizable from Claire Denis’s Friday Night. Jenkins has cited the 2002 film as artistically influential, and Melancholy’s overnight timeframe explicitly recalls Denis’s idiosyncratic assignation story set during a Paris citywide strike.

As they drift, Micah is hopeful and persistent, but even as Jo’ allows herself to be drawn to him, she doesn’t allow him to project a prescriptive kind of blackness onto her or to make her his reflection (mica—a reflective surface). However, the smitten Micah’s neediness is not as severe as San Francisco’s best-known fantasist, Jimmy Stewart’s Scottie, who projected his longings onto the desired Madeleine (Kim Novak), exactly fifty years earlier in Vertigo. Still, diegetically—IRL as we say—Jo’ is cheating on her (white, curator) boyfriend, and Micah is freshly on the rebound from his broken relationship with a white woman. Jo’ resists his notions that they should be (Black) together, which is articulated by an inebriated, plaintive outburst as their evening draws to a close.

As a transplant from Oakland, Jo’ is perhaps more accepting and curious about the city as it is—the city in the moment—as she navigates it. But Micah is born and bred: neighborhoods are name-checked throughout his conversations, and in one of several diversions during the night the two peek into a Housing Rights Committee meeting, the speakers played by actual local political activists discussing the impending loss of rent control throughout the city. All the great things that we love about San Francisco, one of them warns, will be gone overnight. The names the speakers list, like Marina, San Dolores, Bayview, Market Street, Lower Haight, Mission Bay, The Castro, Fillmore, Berkeley, Oakland, all suggest historical shifts that weigh on Micah.

This scene follows the only sequence in full color, when Micah rebuts Jo’s assertion that he dislikes the city. A series of vibrant panoramas are shown illustrating his words, “Naw, I love the city, but I hate the city. San Francisco is beautiful and it’s got nothing to do with privilege. It has nothing to do with Beatniks or hippies or yuppies. It just is.” Like their temporal affair, “it is what it is”—the city where it plays out just is.

In 2018 Reggie Ugwu recorded a conversation for the New York Times featuring Melancholy’s filmmakers as well as admirers. In it, artists such as Lena Waithe and Terence Nance laud Melancholy, citing its significance to their work for its notably nuanced portrayals of Blackness, desire and Black folks. Waithe claims, “Ava DuVernay literally handed me a DVD of it, like it was Nas’s first mixtape or something.” While Nance describes feeling “startled” by the film; “I had never seen anything depicting that world, that pocket of black life.” Cenac’s Micah heralds the protagonists of Joe Talbot’s The Last Black Man in San Francisco, in which the moral dilemma of gentrification is more theatrically presented—maybe Micah is the first Black man.

A more fanciful quarantine double feature would be Medicine for Melancholy and Boots Riley’s Oakland-set Sorry to Bother You, made ten years later. They are opposite in tone and execution, although each film deploys color—or lack thereof—to great effect; Riley’s artist/activists sport saturated primary-hued costumes, and their Oakland neighborhood spaces are lively with clashing patterns and textures but, as the protagonist abandons his friends to creeping gentrification, his funky vintage ensembles are traded for monochromatic suits and his new apartment in the city (San Francisco) boasts a minimal white interior. Ultimately, they both are love stories, which blossom as the characters seek to understand the locus of Black people and of Black weirdness within stormy environments of gentrification and displacement. The works of these contemporary artists are the affirming answer to Micah’s question to Jo’: “Can we be Black and indie?”

Micah’s work personifies the life he seeks in a changing city. He’s a fish tank designer and installer—creating environments that are beautiful and nourishing but which need careful balancing. He has a setup on Fulton St., but he buys his fish in San Leandro. “You might be looking for an angel fish,” he notes, over black-and-white shots of fish tanks. “They may have one angel fish in that whole store. You’re married to that angel fish…but the warehouse they got all kinds of Angels.” For Micah, like L.A., San Francisco is a city of Angels, or at least one perfect seraph, a Black girlfriend for whom he longs.

The next day, after their second night together, we see Angela/Jo’ below from Micah’s apartment window, squinting into the morning sun—preparing to ride away from the story—just across the street from the Angel Café and Deli. She departs as pink, red and green foliaged flowers on the fire escape bloom to full saturation.

Ina Archer is a filmmaker, visual artist, writer, programmer, and Media Conservation and Digital Specialist at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture.