In this weekly column, one writer will send another a new piece of writing about a film they have been watching and pondering over, in the hopes that this will prompt a connection—emotional, thematic, historical, or analytical—to a different film the other has been watching or is inspired to rewatch. This ongoing column will be in the spirit of many past Reverse Shot symposiums, in which writers found connections between seemingly disparate cinematic works, and it will also help us maintain personal connection among our writers and our readers at this uncertain moment.

Lake Mungo

The Internet is no longer the tool of limitless potential and ingenuity it was once heralded to be, somehow cognitively separated from our lurid relationship with social media. We (“we”) each interact with it differently: there are many versions, multitudinous and terrifyingly various, scattered into an oblivion of shards of data by algorithms, invasive devices, corporate greed, and our own biases. I remember the Internet I grew up with as a dark place—literally. I only seemed to visit it late at night, under a blanket. (The conspiracy theorist trolls and white supremacists were already there, but they didn’t seem to have the mandate of violence they do now.) It seemed like you could find anything if you looked hard enough. Type in a random web search, and see where it leads—like page-hopping on Wikipedia, clicking link after link until you find yourself reading about serial killers when all you wanted to know was how many toes an ostrich has. (Two, and three stomachs.) Remember the Silk Road? The black-market organ trade? When you first learned about torrenting? Back then, the Internet felt like the underworld. It seemed as if a vein into the void had been tapped. What was exposed could only be gleaned in bits and pieces. Everything had a veneer. There was always a deeper layer to discover.

Ironically, my current battles with insomnia and anxiety transport me back to that time when I was a kid still learning about living online, when I stayed up on purpose rather than against my will. In quarantine, I’ve been drawn to old comforts and once-viewed curiosities, the Australian found footage horror movie Lake Mungo among them. In my opinion, it’s not particularly revealing to make any statement defending or advocating for certain types of movies suitable to be viewed during a crisis. Just as well, viewing habits are not beholden to stable binaries; happy movies for happy times and so forth. To each their own.

Lake Mungo has been characterized by many publications, including this one, as a “sad” horror movie. It takes the form of a documentary and follows a family in mourning following the death of their 16-year-old daughter. So, among other things, this is a movie about grief. But I’ve always found all ghost stories to be inherently a little sad, no matter the context. What makes Lake Mungo so stirring, so viscerally appealing is how easily and deftly it creates a mirror of the real world, with a slight crack in it. The illusion of ease or realism in filmmaking often signals great effort, or at the very least, great skill. Found footage is a genre trading on a manufactured proximity to reality that is far more explicit about its artifice than traditional cinema. This makes it a potent format for horror when executed well. It also results in a lot of lazy filmmaking, which is why studios can churn these movies out quickly and cheaply—and also why no one tends to take them seriously.

Lake Mungo’s writer-director Joel Anderson understands the thin line that has to be walked with this genre, but also understands that there is so little that can be effective in any kind of story without believable characters and behavior. So the family comes first. Their imperfect accounts of Alice, through interviews, are refreshingly devoid of grave, actorly pauses or melodramatic waterworks. Some of this is likely due to the performers’ lack of scripted dialogue. The small town of Ararat is given significance through expressionistic touches, with stunning images of the surrounding desert and crowded night sky interspersed throughout. Lake Mungo is also a found-footage movie shot on film, which gives it a timeless grainy texture that gets broken whenever we’re shown the digital “found footage” in question. Over the course of 90 minutes, a quiet, melancholic mood builds, until finally the supernatural enters.

This, from Thomas Ligotti’s Conspiracy Against the Human Race, feels like an apt, albeit indirect way of describing Lake Mungo: “From across an immeasurable divide, we brought the supernatural into all that is manifest. Like a faint haze it floats around us. We keep company with ghosts. Their graves are marked in our minds, and they will never be disinterred from the cemeteries of our remembrance...Wherever we go, we know not what expects our arrival but only that it is there.”

For those who haven’t seen the film, it’s worth preserving as many of its quiet and unsettling pleasures as possible. What I’ve said above should serve as preface enough. This is a movie that evoked for me the feeling of being in the dark, surfing through unsolved cases and urban legends. It’s a story that wriggles its way through the cracks in our hopes that the modern world is a place mapped and accounted for. You are not transported to Ararat; you’re drawn in. What happened to Alice turns out to be at once far more mundane and far more unsettling than you could anticipate. And for my money, Lake Mungo has one of the most shocking, skin-tingling twists of any film I’ve seen.

I respect a movie that defies the limitations of its distribution platforms, whether streamed on your laptop or your phone. Lake Mungo isn’t picky about how you watch it. If anything, the more personal the device the better. Anticipating the question as to why watching a horror movie “right now” would be anyone’s cup of tea, I will simply say that, if Lake Mungo works for you, it has the effect of a bracing, cold splash of water. Rather than looking over your shoulder in the dark, the movie gives the far more arresting and disconcerting sense that you have to stare into that darkness to make sure you’re not missing something, that you’re looking closely, until you or something else moves. —Nicholas Russell

L’amour fou

The pervasive air of conspiracy you describe is only too recognizable these days. Even as our physical lives have become ever more restricted and claustrophobic, there’s an increasing awareness of the myriad forces—not exactly benevolent—that continue to operate beyond our control, and the sense of powerlessness engendered by this knowledge is liable to drive anyone insane. More and more, the question seems to be not why people collapse under the weight of their own paranoia, but why they don’t.

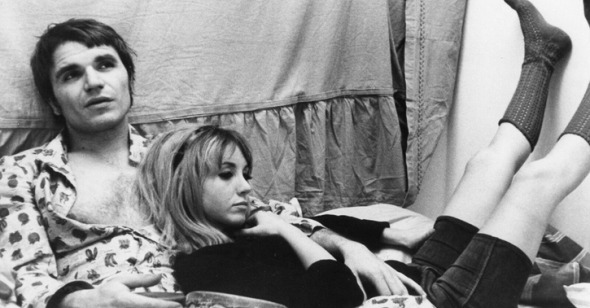

There’s probably no greater filmmaker on this subject than Jacques Rivette, whose work has given me a fair share of frustration, but which has also, over the years, opened up so many intriguing paths of exploration that I find myself returning again and again, hoping to finally break the code. Indeed, your description of Lake Mungo as a “story that wriggles its way through the cracks in our hopes that the modern world is a place mapped and accounted for” applies to my experience of a great many of his films. As Jonathan Rosenbaum once put it, Rivette’s early works “teeter on the edge of madness,” and his 1969 feature L’amour fou, which I recently caught up with on a subpar VHS rip (the only way to see it at home, as far as I’m aware), is the most clearly marked in that respect. Running just over four hours, it directly precedes Rivette’s 13.5-hour Out 1, laying the groundwork for that film’s expansive explorations of conspiracy and theater. In the case of L’amour fou, these twinned subjects flow from a smaller unit: the relationship between Sebastien (Jean-Pierre Kalfon), a director heading a small production of Racine’s Andromaque, and his wife Claire (Bulle Ogier), an actress who abruptly quits during the first rehearsal. This story engine having been established, the film largely moves between the couple’s domestic dramas, the theater troupe’s rehearsals, and Claire’s solitary wanderings through the streets of Paris—all of which follow rough trajectories of disintegration, breakdown, and collapse.

Theater here is a collective, almost utopian enterprise—or that’s how it’s conceived anyway, with the troupe’s bare white rehearsal stage practically sealed off from the outside world, offering Sebastien and his collaborators a chance to remake the world as they please. By contrast, the apartment Claire shares with Sebastien, where she stages her own paranoiac drama, continually serves as a gateway to the city and its endless possibilities, which bring her farther and farther out as the film unfolds. (While compiling a sort of dossier on her husband’s activities, she frantically records snatches of radio transmissions and even street sounds, and at one point attempts to steal a basset hound.) Eventually recognizing that something must give way in their relationship, the couple abandon their respective pursuits and beat a retreat back to their bedroom, where they together launch an extended assault on the space, scrawling on and then stripping away wallpaper, reorganizing and/or smashing furniture, and generally upending the room’s previous order.

This protracted sequence transforms the pair’s familiar domestic terrain into an arena of uninhibited play—something like the destructiveness of Bringing Up Baby without the mollifying comedy. Carried out literally, this exercise would be useful to precisely no one, but it is crucial in understanding Rivette’s fundamental conceptions of identity. What’s significant is that through all this activity, Claire isn’t looking to reveal some sort of inner truth, some essence of her being that has heretofore been suppressed. For her at least, there was never any doubt that she was merely adopting and then discarding various roles and postures: “We've played too much, I've had enough,” she eventually says to Sebastien, exhausted. Through this exercise, she eventually locates a point of departure, allowing her to escape from her previous existence, while Sebastien, for his part, is only beginning to realize that he might need to do so himself.

Not exactly the most affirmative of films, L’amour fou ends on a note not so far from the Ligotti quote you mentioned earlier: sitting in his ruined, empty apartment, keeping company with the ghosts, Sebastian is all too aware of the hollow husk of his own life. But amidst the rubble, there’s also a glimmer of hope. For if identity and human behavior, in Rivette’s view, are rooted in performance and play, then we are not locked into our roles—and thus into endless cycles of paranoia and claustrophobia and fear. Like Claire, like Sebastien, perhaps we still have the option of starting anew. —Lawrence Garcia