Rattle and Hum

Ela Bittencourt on Railway Sleepers

Railway Sleepers plays Sunday, January 14, as part of Museum of the Moving Image’s First Look 2018.

Ever since the Lumière brothers’ locomotive arrived at the station, the train has been a mass symbol of mobility—both literal, conquering sprawling terrain, and metaphorical, of prosperity embodied by steam power and the machine. And as depicted in Thai director Sompot Chidgasornpongse's debut feature, Railway Sleepers (2016), train lines are not just beacons of progress but also ambassadors of national unity. To this effect, the documentary opens with a quote from Thai king Rama V, who in 1893 announced his vision for a unified country, thanks to his inauguration of the Thai railroad system. And while Chidgasornpongse's understated, visually eloquent film does not aim to necessarily dismantle this vision as a hopeless myth, the more mundane reality it portrays offers plenty of proof.

Though Railway Sleepers begins with a succinct history lesson—black-and-white archival images depicting the construction of the first Thai lines flash onscreen while a teacher whom we hear off camera provides a few basic facts about old locomotives and train traffic control, and prods his young students’ knowledge of trains—this dogmatic approach is discarded immediately. The teacher’s voice competes with the constant clickety-clack of the train’s wheels, the mechanical song that will accompany us for the rest of the journey. This monotonic soundtrack embodies Chidgasornpongse's understated method: to use only what’s there, with diegetic sound and mostly static camera, observing actual train passengers. It’s an expansive visual travel journal—Chidgasornpongse rode all of Thailand’s train lines over the course of six years—though on screen it seems as though it’s all happening in a single day (represented in 102 minutes of footage).

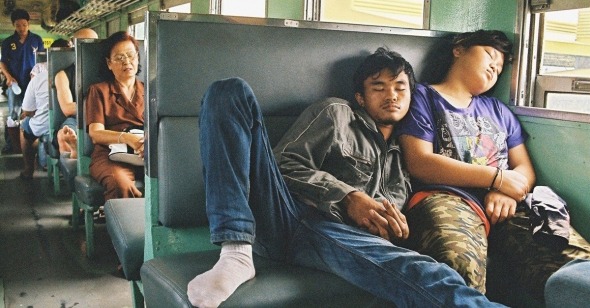

The result is beguiling: a lullaby of sorts, it seduces with its rhythm, while every once in a while, a sudden, odd flash stirs us to alertness. A small boy will peek shyly at the camera as his classmates surround him to admire his just pulled-out tooth. In the lower-class compartment, a fight will break out over who paid and is the rightful owner of a seat. Another time, a group of men with drums will break into a song and encourage others to join in. But for the most part, the hours bleed languidly into one another. Chidgasornpongse’s patient eye breaks the monotony with wistful humor: a green insect clings to the window’s metal frame as the wind lashes at its wings; it, too, is a passenger. Along with humans, there are traveling dogs and chickens. Endless vendors stream from car to car, offering guavas and fermented pork. There is a sense that in the lower compartments, to travel is to be constantly immersed in sounds and flavors, a clutter and crowding that requires stoic resolve—in one shot, a frail old woman is nearly crushed between frolicking children and a passing vendor. In another, women gossip about the earlier fight that broke out over the seat. Thus King Rama V’s boasting vision slowly gives way to a humbler assessment: the trains’ roofs leak when rain pounds them, the second-class compartments are shoddy, steamy, and cramped.

Not much of Thailand’s political or social tensions seem to filter into the film: Chidgasornpongse fluidly progresses through the compartments, the camera fixated on the prosaic, registering faces and poses more often than conversations. In one moment, military police appear, presumably to deter any acts of terrorism. But for the most part, the journey proceeds in dreamlike fashion, some passengers frozen and meditative (such as the Buddhist monks), others reading, still others dozing. Complete stillness—if we ignore the train’s constant rattling—invades only the couchette compartments, where the quiet is eerie, after witnessing so much bustle. Late in the film, two strangers—we eventually recognize one of them as the filmmaker himself—converse quietly in a private compartment. “Do you travel often?” the filmmaker asks. “Yes, for work,” replies the other. “I’ve been almost everywhere.” This “everywhere” turns out to be quite metaphorical: in the stories he tells, the mysterious passenger goes back in time to when people traveled by caravan. Is he the king’s ghost, we might ask? But he could also be the king’s loyal subject, aka a train inspector, who recalls the first Thai train line.

Chidgasornpongse leaves his film open-ended, but one of the lines that refers to the king’s ambitions, as expressed by the mysterious inspector—“to civilize and to centralize”—has a bitter tinge to it, a reminder that the colonizing past has left its mark on the lush terrain we have been watching from the passing trains. The landscape’s inextricable from history. To emphasize this, Chidgasornpongse again returns to archival imagery. “Were all the train staff foreigners? Any Thais?” he asks the inspector. “None.” This note of exclusion is emphasized by the fact that the “ghost” himself is British, and refers to locals, in outdated colonial parlance, as “coolies.”

The journey ends on a wistful note, as the filmmaker confesses to the other passenger in the compartment that train rides have lost their sheen: what had once been a religious rite and a family event has become commonplace and solitary—a disenchantment that echoes our entire technological age. As the sun breaks and begins to fill the desolate corridors of the first-class wagon, the inspector dozes calmly on his perch. But from some distance, the camera eyeing him coolly, he’s already fading, with shadows obscuring him—both an anonymous stranger, and our guide into the nebulous past.