Strange Geometry

Jordan Cronk on the films of Björn Kämmerer

Films by Björn Kämmerer plays Saturday, January 23, at Museum of the Moving Image as part of First Look 2016.

It’s been 120 years since The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station (1896), and it can feel more than a little redundant to note that one of cinema’s foremost capabilities lies in its freedom to manipulate perspective. That said, if one were to outline the chief innovations in modern filmmaking, they would likely situate around a number of advances made in the arena of visual proficiency—namely, in what viewers see and how they see it. As expertly as any artist of his generation, the German-born, Austria-based filmmaker Björn Kämmerer—subject of a nine-film program at the Museum of the Moving Image’s fifth annual First Look Festival—exemplifies the avant-garde’s fundamental interest in this phenomenon, in cinema’s unique ability to negotiate the complexities of optical intrigue. Utilizing the medium as a means to investigate material reality and the manner by which we conceive of the physical relationship between form and the spaces in which these figural manifestations reside, Kämmerer has, over ten years and as many films, established himself as one of Europe’s most exciting and formally economic young filmmakers.

Kämmerer’s career has thus far been split rather conveniently into two seemingly discrete phases that nonetheless evidence some intriguing parallels when considered side-by-side. His early output consists largely of experiments with found footage and vintage bits of celluloid he proceeds to interrogate on a micro level, often looping or manipulating individual movements or moments in an effort at isolating unassuming, frame-specific gestures. Both Sicherheitsalarm (2003) and Aim (2005), for example, repurpose genre films, the former whittling down a 400-minute science-fiction production into a two-minute comedy of verbal acrobatics, the latter turning a wild west shootout into a brief, one-sided round of errant gunfire. In Sicherheitsalarm, enunciations of various German words (“Kommandant! Sicherheitsalarm!”) are fashioned into an atonal symphony of enervated phrasings, with each character caught in a bout of cyclical pronouncements. The dissonance in Aim, by contrast, is administered via a discharging six-shooter, as two cowboys meet in a remote mountain pass, readying themselves for a deadly showdown. In Kämmerer’s montage, however, only one gunman is allowed to fire, which he does in a rapid succession of repeated motion, as reversals to the confused look of the second man are employed as humorous reaction shots.

The action in Escalator (2006) and Dawn (2007) yields less comedic results but is equally concerned with small variations of recurrent motion. Rather than simply loop a short sequence of a young boy descending a staircase, as in Escalator, or a shot of a woman reacting to the overhead glare of streetlamp, as in Dawn, Kämmerer opts to reverse––and in the case of the former, flip––the images at key junctures, a conventional enough technique which here alters the figures’ movements just enough to highlight the arbitrary nature of their prescribed trajectories. A more recent application of this concept can be found in Trigger (2014), a work comprised of original footage wherein images of marksmanship targets are edited into a rapid collection of anonymous gunmen. Slight differentiations in their stances and expressions become more and more pronounced as Kämmerer accelerates his montage, though the basic outline of the figures remains intact. Coming a number of years after his early experiments, Trigger can’t help but feel––in the best sense––like a deferred refinement of this formative conceit, simultaneously highlighting the symmetry and discrepancies to be found in objects or materials of similar countenance.

Trigger notwithstanding, the majority of Kämmerer’s recent output (all of which has been produced on 35mm) has been created in the filmmaker’s personal studio, and in each case reflects a meticulous conceptual discipline that could only be achieved in a controlled environment. One can sense this organizational maxim most immediately in Gyre (2009), in which equilateral panes of white light move from right to left across the frame in regulated measures. But as in many of Kämmerer’s recent films, the viewer’s perception is altered when subtle adjustments are made to the composition. In Gyre the alteration is to the lighting scheme and to the position of the camera; as Kämmerer delicately brightens the image, what at first appears to be unilateral light formations reveal themselves as openings within an octagonal wooden box rotating on a fixed axis. As these details slowly become visible and the camera angle shifts slightly right, the focal point of the composition likewise shifts from the window-like apertures to the grain of the spinning structure itself, drawing attention away from the light source and onto the carefully calibrated apparatus facilitating the rotation. In what has proven to be a recurring motif in Kämmerer’s work, the distance between Gyre’s initial sensory effects and the visual articulation of its assemblage is both something to be experienced in real-time and retroactively regarded for the efficiency of its employment.

The component parts of Turret (2011) are more difficult to trace. As the film begins, shafts of vertical light are spinning toward a mid-screen vanishing point. The most immediate response is to locate a pattern within the oscillations, which remains difficult even as the formations appear to be emanating in tandem from the edges of the frame. As in Gyre, the compositional elements of the film gradually take shape within the mind’s eye, as faint reflections begin to suggest glass surfaces and quick glimpses of wooden fixtures confirm an architectural foundation. True to these material intimations, Turret’s visual illusions were produced by mounting numerous window casements atop spinning turnstiles, creating an intricate play of light and movement by simply exploiting the expressive properties of familiar domestic objects. A similar concept drives the action in Louver (2013), in which fluorescent light fixtures swing asymmetrically through the frame, producing vertical delineations in a dimensionless space. Even in a work as seemingly anomalous as Torque (2012), wherein Kämmerer’s camera horizontally tracks (in one uninterrupted shot) the geometric formations of a series of converging railroad tracks, a comparable sense of spatial organization and perceptual interest can be felt in the film’s precisely calculated visual construction. In that sense, one might say that Kämmerer is returning the notion of structural filmmaking to its most elemental state.

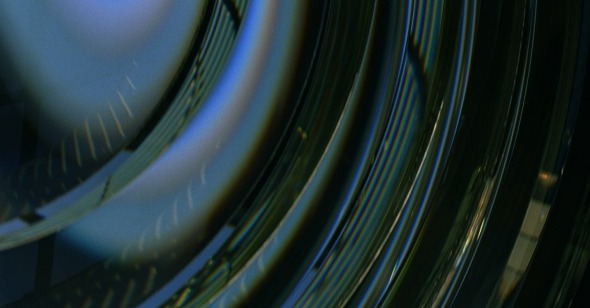

It’s therefore unsurprising to find that Kämmerer’s latest film, Navigator (2015), is both his most refined and conceptually ambitious to date. Again taking a reflective surface as his primary visual device, Kämmerer here shoots the beveled edges of a set of nautical mirrors from inside a lighthouse, each of which arc and curve in perpetual motion through a succession of static compositions. Situated in extreme close-up, the camera catches every incremental change in light and scenery emanating from the surface of the structure, which appears to shape-shift as it rotates before the lens. Kämmerer edits these movements into a montage that disrupts the almost liquid flow of the proceedings, shifting angles and inverting images in such deceptive fashion as to suggest a living, breathing, mirrored motion-machine. The effect is one of vast depth and disorienting claustrophobia, tactile pleasure and ambiguous provenance. With Navigator, Kämmerer appears to have reached a kind of conceptual apotheosis. With no way in or out of the film, and with any definitive sense of perspective subverted by a seemingly limitless visual spectrum, the viewer is left to conceive of a space within these coordinates unique to their own imagination. By consolidating his formal and thematic interests into a singular aesthetic object, Kämmerer may have opened up an entirely new way of seeing.