Body Shop

By Benjamin Mercer

La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet

Dir. Frederick Wiseman, U.S., Zipporah Films

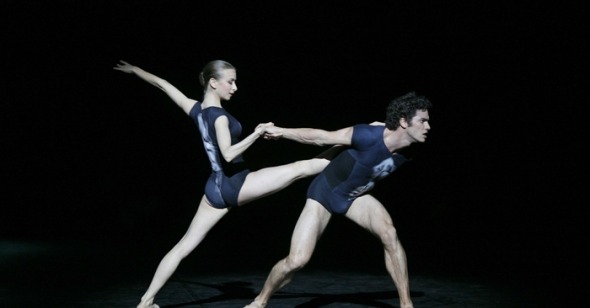

La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet, Frederick Wiseman’s 38th film in about as many years, and his second about dance (after 1995’s Ballet), begins with a series of shots of Paris, immediately establishing the renowned company as subject to the city’s daily grind. Though La Danse features a number of administrative meetings and extended glimpses of finished performances, Wiseman’s primary interest is in the grueling rehearsals. Dancers run through their movements in mirror-lined rooms, usually to the accompaniment of a pianist in the corner, and choreographers, exacting and for the most part stinting on praise, pick those movements apart, suggesting ways to make them more expressive. What specific ballet is being rehearsed and who is doing the rehearsing are more or less beside the point. The fragments of performances shown, mostly in the latter half of the film, rarely correspond directly to the parts we see painstakingly practiced; even during the performances Wiseman and cinematographer John Davey seem determined not to acknowledge the presence of the audience. La Danse is less about the development of certain specific movements executed by the dancers than it is about the process of development itself. The emphasis is on the interplay between the able-bodied dancers and the usually older choreographers, more carefully attuned to the nuances of movements but not (or, perhaps, no longer) lithe enough to do the dancing themselves.

Though the choreographers and dancers communicate through a language of pliés, glissades, and arabesques that is a little difficult for someone with no prior knowledge of ballet to decipher—and Wiseman, famous for his strictly observational style and his total forgoing of explanatory titles or voiceover-delivered context, naturally provides no glossary—this is not necessarily a “ballet film.” The few lapses in the dance argot are particularly amusing: star dancer Laetitia Pujol chafes under the technical direction of a choreographer and serenely utters the most exasperated comment in the film, “You blame me too much”; an English choreographer negotiates the language barrier by miming what he wants to see from his dancers; others discuss the story of Medea, leading up to their performance of Angelin Preljocaj’s adaptation of the Greek myth, in terms of X-Men and Edward Scissorhands. The rare expression of frustration and the references to considerably more mainstream entertainments serve to humanize the dancers, but the film’s main focus remains the total, almost superhuman dedication required of them. The ballet’s artistic director, Brigitte Lefèvre, quotes the late choreographer Maurice Bèjart at one point: dancers are “half nun, half boxer.”

Above all else, Wiseman is an anatomist of large organizations. He professes to do little preparatory research for his films; the access is the thing. From his 1967 debut, Titicut Follies, to 2007’s State Legislature, he has produced closely observed case studies of various organizations via a remarkably consistent vérité approach. He does all this as well in La Danse, though not so much in the extensive rehearsal footage. Wiseman and Davey masterfully convey in just a few broad strokes a spatial conception of the massive building that houses the ballet and its 2,200-velvet-seat performance space, the Palais Garnier. These brief detours into the building’s vacant hallways, stairwells, and nether basement regions provide a sort of Way Things Work cross section of the palatial building, depicting it not only as a hive of activity but also as a churning machine. Wiseman and Davey visit more bustling spaces as well: the costume workshop; the roof, where a beekeeper toils away; and the cafeteria, where a chalkboard listing the day’s menu amusingly depicts a large mug of beer, which presumably none of the dancers dining there are about to imbibe.

These space explorations function formally as a kind of connective tissue between rehearsals and the scenes in which the nitty-gritty institutional side of the ballet is explored. This separate strand of the film features Lefèvre, a grande dame glimpsed in meetings trying to brainstorm special perks for big donors—among them, a group from the now-defunct investment bank Lehman Brothers—and to defend her program’s careful balance of the classical and the contemporary. Floors are swept, programs are hawked, and lunch is served, but the business side of the film by and large sticks to Lefèvre’s agenda, which also includes counseling impressionable young dancers and negotiating a retirement age of 40 for the members of her corps. Most of the ugly realities of ballet seen in La Danse are confronted when Lefèvre is in the room. Lefèvre concludes the dismissal of the dancer by observing, “You’ve lost weight.” It seems more a criticism than a sign of approval, code for “You’ve lost too much weight.” There are no vomiting mescaline users (Wiseman’s 1968 documentary Hospital) or stripped naked, screaming schizophrenics (Titicut Follies) populating the corridors of the Palais Garnier, but it’s clear this way of life is not without its own brutalities, no matter how genteelly they are dispensed.

However engaging it is to watch Lefèvre in action, though, her part of the film often feels perfunctory, as it’s never quite in rhythm with the considerably longer rehearsal stretches. The primary concern of any ballet company will naturally be the ballet, so it’s hard to fault Wiseman’s privileging of practice and performance footage, but he often seems to be cutting together two discrete films: one a simple appreciation of the expressive power of agile bodies in motion, the other a more traditional Wiseman institution dissection. Both of these are intermittently delightful, but La Danse is not, like Wiseman’s best work, fully immersive.