Dark Passage

By Leo Goldsmith

Horse Money

Dir. Pedro Costa, 2014, Portugal, Cinema Guild

All plot synopses are necessarily attenuations, but for Horse Money any summary feels especially futile, or even violent, a crude reduction of its complex network of impossible geographies, fuzzy memories, and jumbled chronologies. Its official film festival synopsis—“While the young captains lead the revolution in the streets, the people of Fontainhas search for Ventura, lost in the woods”—is almost comically unforthcoming. In his Q&A after the premiere at the New York Film Festival, Costa said he wanted to replicate the “fast” style of films of the 1940s—films that moved quickly, not giving the viewer time to think. Which is not to say the film is particularly fleet-footed—it is indeed almost crippling in its intense stasis. But in contrast with Costa’s last two narrative features—both well over two hours—Horse Money is a relatively trim 104 minutes. Here, Costa has distilled his already lean mode of production into a quick but extremely dense film, working (according to him) with a budget of 100,000 Euros. (Such are the conditions of filmmaking in Portugal, where state support for new films was suspended in 2012—the so-called “year zero of Portuguese cinema”—right before Costa made the film.)

But despite its structural density, it is rather Costa’s process that seems the main obstacle to any easy understanding of the film. As always with Costa, his seemingly guileless, unapologetic slippage between documentary and narrative modes presents problems for critics and spectators alike. This elision of registers is compounded by Horse Money's first images: photographs by Jacob Riis from his 1890 book How the Other Half Lives, which documents the tenement dwellers of 1880s New York City. Riis’s images function both as raw historical fragments and vivid dreamscapes—records of the past and entryways for the imagination. In Costa’s film, they’re accompanied by dead silence: blurred faces, low-ceilinged rooms, a goat, a corpse, winding alleys with washing lines, small makeshift groups of people staring idly, maybe aggressively back at the camera. In Riis’s images, as in Costa’s, there is a unresolved, anxious quality, a suggestion that the relationship between those in front of and behind the camera is either one of social and political solidarity—even, ideally, collaboration—or of exploitation, aestheticization, a kind of poverty tourism.

The question of how best to understand this relationship has dogged Costa’s films since he began working with the inhabitants of the Lisbon slum of Fontainhas with his 1997 Ossos. Jeanette Samyn and Jonathon Sturgeon, in an essay for n+1, note that evaluators of Costa’s work tend to divide into two camps: detractors, like Armond White, who regard it as slum poetry that crassly aestheticizes poverty and despair, and the “Vote for Pedro” contingent, mainly associated with Cinema Scope, who hail Costa as a poet of Lisbon's migrant and underground populations. In their conversation about Horse Money’s screening at the New York Film Festival for Senses of Cinema, Daniel Fairfax and Joshua Sperling restage this debate in rather more nuanced terms, offering opposing sentiments about the film’s qualities and in particular the relationship between its director and its lead actor, Ventura Jose Tavares Borges, that the film implies. Sperling finds the film “mannered and cold. As a hybrid of high-flown avant-gardism and theatrical documentary it may be interesting, but as a document of suffering I found it to be deeply misguided.” Fairfax, for his part, finds that in the film “a sense of profound solidarity and even love exists between [Costa] and Ventura, one which has encompassed the films they have made together over the course of more than a decade.”

The disagreement between Sperling and Fairfax turns upon a set of questions familiar to discussions of the politics of representation in cinema and in Costa’s body of work in particular: questions concerning the proper means of depicting the experiences of poverty, subalterity, and trauma, and indeed the question of who the film is by, about, and for. Who is Ventura, exactly? Who is he for Costa and for us? Are we to see him as an actor or a subject, a collaborator or raw material for Costa’s cinema?

Costa himself clearly does not want the answers to these questions to come easily, if at all. Costa, in a lecture at the Tokyo Film School in 2004: “It’s very rare today that a spectator sees a good film, he always sees himself, sees what he wants to see. When he begins, rarely, to see a film, it’s when the film doesn’t let him enter, when there’s a door that says to him: ‘Don't come in.’ That’s when he can enter. The spectator can see a film if something on the screen resists him.”

For the philosopher Jacques Rancière, Costa’s work is notable as a political project for its lack of interest both in examining the power structures behind the marginalization of the poor, and in setting the stage for political action or collective struggle. “The wish to explain and mobilize thus seems to be missing from Costa’s project,” he writes. “And his artistic prejudices themselves seem opposed to the whole tradition of documentary art.” But, for Rancière, this is far from an indictment; indeed, he sees Costa’s work as a total reconception of cinema’s political role in an age in which the medium is as much a tool of exploitation as it is a means of representing, of exposing, such exploitation. Costa’s is a different “art of the poor” that avoids seductive psychologizing and satisfyingly sociological explanations alike. Instead, Costa’s cinema is “an art of life and sharing,” one that creates an arena of images, affects, and experiences, but refuses to assimilate or predigest them for the viewer. In Rancière's view, cinema “should consent to being merely the surface on which the experience of those relegated to the margins of economic circuits and social pathways seeks to be ciphered in new forms.”

Surfaces and pathways: perhaps the answer lies in Costa’s notion of space—a new space, and the doors one must open in order to access it. This is, after all, the question that has preoccupied all of Costa’s Fontainhas films: how to create a new space when one’s home, one’s neighborhood, is being demolished? Fontainhas was literally crumbling as he made 2000’s In Vanda’s Room. In 2006’s Colossal Youth, the neighborhood’s inhabitants drift between the last remnants of the neighborhood and its surreal counter-image: the hard-edged, sunbaked surfaces of the state-sponsored apartment block to which they have been forcibly relocated. Is it possible for cinema to offer an imaginary, temporary space for a population in transit, on the verge of dissolution and compartmentalization?

The further Costa’s films wander from Vanda’s rooms, the more they become caught in transitional spaces, in alleys and passageways. Most of In Vanda’s Room and Colossal Youth take place in full sun, refracted through corridors and cracks in the walls; Horse Money is a night film, a nocturne in black and gold. The features of Costa’s mysterious, heterotopic Lisbon have now been completely evacuated, emptied out, so that the image itself is often mostly black negative space, as if the architecture itself has been erased, the image scratched out. Even the now-trademark texture of Costa’s video resolution is different, its busy pixel-grain calmed and flattened into deep, fathomless pools.

This is a new approach for Costa, and quite a shocking one. It’s still unmistakably Costa’s work: in the exquisite precision of its camera and lighting placement, its uncomfortably close sound design, and in its use of consumer-grade digital video. But here each of these is heightened and distinct from his previous work: the framing is not simply uncanny but almost spatially impossible; the soundtrack is often dead silent, at other times so hushed that you can hear Ventura’s hands shaking.

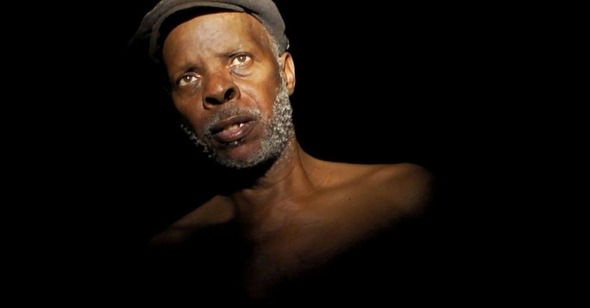

Here, the familiar locations of Costa’s films become something still more alien—a kind of purgatory, or oblivion. When the montage of Riis photographs ends and the film’s action begins, Ventura descends, half-naked, into shadow, through a nightmarish underworld of networked corridors that seem to lead nowhere. “Hospitals, prisons, rooms, it’s all the same, it’s always underground,” Costa said in an interview with Cinema Scope. “It’s not one—it’s millions of hospitals and corridors and doors, so there’s no match. It’s a film where nothing matches. The doors are always different, but they are always hospitals, prisons, with the same sound, the same heaviness.” In Horse Money, the messy, sprawling demimonde of Fontainhas has been definitively replaced by a set of interchangeable and unforgiving institutions—shadows of a necropolitical architecture that fully dominates and configures Ventura’s subconscious. Soldiers and doctors prowl these passageways, leading him, limp and glassy-eyed, deeper underground.

When Ventura descends these dark passages and corridors at the film’s outset—descending toward the camera, out of the darkness and very slowly into focus—he strikes a gaunt, inhuman figure that looks like no one so much as Nosferatu, clad in a worker’s cap and red undies, hollow-eyed with his long fingers continually moving in little neurological spasms. In fact, if Horse Money is at all classifiable, it’s as a horror film. Critics often grasp for cinematic points of reference to situate themselves in Costa’s work. At Q&As with the director, a question will inevitably be asked about connections between his films and those of John Ford, which Costa, although an evident cinephile, will then dismiss as crazy. Nevertheless, In Vanda's Room, with its excessively detailed mise-en-scène, is haunted by the ghost of melodrama; and for all its chilling sequences, Colossal Youth is a comedy of deadpan longueurs, a ground-level Mon oncle hiding inside deep, mazelike interiors. Horse Money recalls the cinema of F. W. Murnau, and not just because of its main character’s vampiric movements. Costa’s expressionistic framing and geometries seem to warp the rigid 4:3 aspect ratio of the silent cinema, which here seems almost vertical, always catching more of the ceiling or floor than would seem possible for such a composition.

Costa has said that, as with his previous work, Horse Money was constructed from anecdotes that Ventura has told him over the years, “stories about this prison—he calls it a prison [where] he fell into a deep sleep.” Together, Costa and Ventura seem to have reconstructed this prison—from catacombs, and offices, and decrepit 1970s-era hospital interiors—perhaps as an act of exorcism. Costa, again: “Some people say they make films to remember, I think we make films to forget. This is really to forget, to be over with.”

But Costa’s film also makes it clear that these nightmares are intractable, inscribed into Ventura’s very body, which is visibly wracked by nervous disease. (“I know my sickness,” he tells one faceless doctor.) Even if the images are often obscure, inscrutable, they have a physical heft. Here, objects take on an almost fetishistic intensity: a pen, a telephone, a passport, a spoon, a knife. And the ghosts and demons that wander these spaces have a weight of their own. In Costa’s short film The Rabbit Hunters, Ventura lamented, “My hands shake and I drop the snuff. A lot of departed spirits walk with me.” In Horse Money, there are not just doctors and soldiers, but Ventura’s half-recognized friends and relatives: friends he used to work with, now fellow prisoners who have also been damaged; his nephew Benvindo, who has been sitting in an office waiting room for twenty years, waiting for his salary; Joaquim, in a blood-red, ruffled shirt, who whispers to him that he must “Confess.” Most important among these is Vitalina, whose role in this world is unclear. Leather-jacketed and rolling a suitcase through black city courtyards, she speaks to Ventura in a gravelly whisper. Is she a doctor? Priestess? Or simply another wanderer and a widow, another lost soul?

Ventura’s final encounter—with a semi-animate bronze statue of the Unknown Soldier in the chrome-walled confines of a hospital elevator—finally offers us a historical context in which to situate Ventura’s trauma. With his disembodied cries of “Viva the revolutionary army!” the soldier hints back to Portugal’s Carnation Revolution, a movement of both military and popular resistance that overthrew the authoritarian Estado Novo in 1974. But in Ventura’s nightmare vision, popular revolution takes on less liberatory claims, as the soldier demands, “Are you with the people, Ventura?” It is clear that, for Ventura and for the other immigrant populations within Portugal, this was not his revolution. The soldier reminds him: “You are, and you have nothing.”

In this twenty-minute sequence, filmed within the cramped confines of an elevator, a more crucial question of space emerges: one of distance and proximity. The question of distance—between the people of the nation-state and those who exist on its margins—might be more important than the notion of Costa’s presumed distance from Ventura, his subject or his collaborator, his friend or his neocolonial muse. Indeed, a certain kind of distance—between the film and its spectator or critic—may be more important than the false proximity of cinema, especially that of a documentary image that purports to bring you close enough to something so as to understand it. (Costa: “That also is very important in the cinema: to love at a distance.”)

With his Fontainhas trilogy, Costa said that he began and ended each project with the people in them, developing and adapting their contributions into the film, which he would finally screen for those people in their neighborhood. This notion of the neighborhood implies a physical proximity in the process or with the potentiality of becoming a community. Horse Money implies a darker, more transitional space. As in Riis’s photographs, figures hover in the frame, themselves transitional. Costa seems to restage Riis’s images for Horse Money’s central section, with his own cast of collaborators sitting in their abodes. The sequence takes on the form, curiously, of a little music video: as a song by the Cape Verdean group Os Tubarões, with its lyrics that speak of dry roots struggling to reach deep buried water, land ownership, migration, return, we see each figure captured in still tableaux, sitting in his or her bedroom or kitchen. In the last of these, right in the center of the frame, a doorway opens almost imperceptibly—a crack, an escape hatch leading somewhere beyond the confines of the film.