No End in Sight

by Jordan Cronk

No

Dir. Pablo LarraĂn, Chile, Sony Pictures Classics

Over the past few years, director Pablo LarraĂn has become one of Chile’s most highly regarded artistic ambassadors, producing a series of stylistically diverse films that have taken on Augusto Pinochet’s violent and unscrupulous reign, which lasted in his country from 1974 until 1990. The key to LarraĂn’s effectiveness thus far has been his ability to strategically, and from different angles, analyze issues surrounding the political stain the dictator left on Chile. Tony Manero, the first in LarraĂn’s loose Pinochet trilogy, approached the era most symbolically. Set in 1978 in the wake of the pop-culture fervor over Saturday Night Fever, the film dissects the psychology of a disenchanted civilian whose obsessive mimicry of John Travolta’s disco-dancing icon can barely mask a murderous split-personality, his alienation posited as a pointed outgrowth of his noxious surroundings. For his follow-up, the darker and somehow even more bleak Post Mortem, LarraĂn would aim his critique at the dawn of Pinochet’s rise to power. Patiently observing a pale-faced morgue typist as he stoically investigates the disappearance of a local burlesque dancer, Post Mortem literally concludes in a state of ambiguous transition for its characters and the culture they symbolize, but also, it turns out, for LarraĂn himself.

No, LarraĂn’s latest film and final chapter in his Pinochet indictment, represents a clean break from the allegorical conceits of his prior two films. A historical account of the events surrounding a referendum called for at the expense of Pinochet in 1988 and, more specifically, a behind-the-scenes retelling of the campaign which strove to thwart his final term, No offers an admirable, detailed reconstruction of the period. Less metaphorically ambitious than what we’ve come to expect from LarraĂn, the film is nonetheless passionately staged with a feel of disarming authenticity. Shooting on U-matic videotape to replicate the look and feel of eighties-grade television stock, LarraĂn effortlessly immerses the viewer in the era’s period design and analogue advances, creating a space both nostalgic and tangibly alive. If LarraĂn’s chosen aesthetic is the film’s most immediate talking point, it’s also arguably its most memorable aspect, and not for any deficiency in LarraĂn’s storytelling ability so much as the predictable arc of its true-to-life narrative.

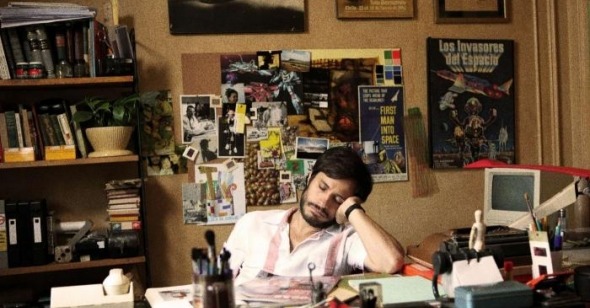

Starring Gael GarcĂa Bernal as RenĂ© Saavedra, an ad executive tasked with creating a counter-campaign to rally a nation brainwashed by its leader’s venomous directives, the film paints its intimately scaled story in small, precise brush strokes. Adhering to the period backdrop and factual intricacies of his built-in narrative, screenwriter Pedro Peirano sketches a small ensemble of behind-the-scenes players, with Bernal’s Saavedra joined in his efforts by LarraĂn regular Alfredo Castro as Lucho Guzmán and a respectable list of some of Spanish cinema’s most dependable character actors. The film, however, is less vocational in the vein of a character exposĂ© like Mad Men than a sober historical report Ă la Good Night, and Good Luck. In fact, George Clooney’s McCarthy-era dramatization makes for a particularly compelling American counterpart to LarraĂn’s similarly disenchanted political reconstruction. Both films not only adopt a specific visual aesthetic as a means to evoke an era, but each also examines the inner workings of bureaucratic malfeasance by zeroing in on the contradictions and questionable practices of each nation’s news intelligence. They also both sacrifice dynamism in favor of historical validity.

It may be dubious to label political sagas of this nature as “uncinematic,” particularly with films such as Aleksandr Sokurov’s The Sun and, further back, Robert Altman’s Secret Honor or even Oliver Stone’s nineties twofer, JFK and Nixon, memorably proving otherwise. What these films all featured to varying degrees of success, however, were unique narrative perspectives that approached their subjects with equal parts reverence and aesthetic ambition. And each of these works transformed fairly mundane or historically exhausted events into bracing audiovisual documents. No, for its part, maintains an admirable verisimilitude, but outside of its surface employment of period-appropriate analogue stock, it’s a fairly conventional nonfiction narrative lacking an inherent drama that could have rendered the film more involving than its one-dimensional framework allows. LarraĂn’s sporadic inclusion of archival footage from the era is welcome and highly effective in lending the film some historical context, though this only highlights the divide between the grave calamity of the actual events and LarraĂn and Peirano’s more dialogue driven re-creation.

Still, LarraĂn has a meticulous eye and a unique ability to coax fully realized yet unassuming performances from his actors. Outside of Castro’s turn as RaĂşl Peralta in Tony Manero, LarraĂn’s characters have been fairly reserved emotionally, internalizing energy in ways that Peralta couldn’t quite manage. This has led LarraĂn’s last two features in a more sedate direction, but the slow burning series of interactions in No are set in relief via a newfound sense of humor. LarraĂn has some fun with the dated ad campaigns and overly industrious commercials the team concocts, while specific character traits of some of the less adroit staff are exploited to lighthearted ends. In fact, it’s this streak of levity that keeps the film from flatlining at times. His outlook, no doubt spurred on by a lingering sense of cultural discontent, could not seem to move much further into darkness without sacrificing the curiosity factor that could liberate his films from complete emotional oppression. So LarraĂn’s move toward a less allegorical cinema has divulged both intriguing new narrative potentialities and perhaps revealed some limitations in his narrative tool set. No, then, ultimately works best when viewed within the context of LarraĂn’s growing corpus, not only as culmination of this thematic trilogy but as further evidence of an artist curious to explore the reaches of his medium’s visual language.