Of Vice and Mann

By Justin Stewart

Miami Vice

Dir. Michael Mann, U.S., Universal

Everything on Michael Mann's film and television resume predicts the exact Miami Vice that he made, which isn't to say that it's his masterpiece. Heat is the better film, but Miami Vice is the messy towel-wringing of all of Mann's thematic, moralistic, and, most importantly, stylistic pet obsessions up to this point. It's such a declaratory explosion that it would seem necessary for the director to take another Last of the Mohicans or Insider-style detour next, as he may have milked moody cop bombast dry, albeit gloriously. (Perhaps Mann disagrees – the lead character in his next planned film is a federal agent).

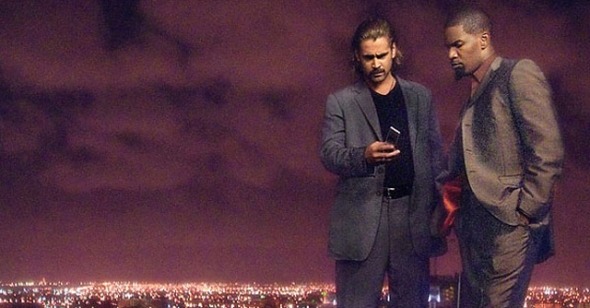

Where his other films are sleek and streamlined (if not always short), Miami Vice at first appears to be in disarray. The first half hour or so is a borderline incoherent cacophony of seedy nightclub goings-on, beatings, barked cellphone conversations about various people who haven't been introduced, and indecipherable vice squad jargon. It's exciting, we want to be a part of what's happening, but there's the feeling that Mann has banked too hard on television-gleaned audience savvy. Finally, a scene of shower foreplay and tender, convincing sex between Detectives Tubbs (Jamie Foxx) and Trudy Joplin (Naomie Harris) cools the movie's tempo, letting us bitterly admit the aptness of the opening's aggressive immersion. It sets up a template for what follows: scenes of tactile, feel-the-heat-of-the-barrel gun violence punctuated by intricate machinating and interludes of spectacularly palpable lovemaking and romance.

The beauty of the latter is Miami Vice's crucial cap feather. The Jada Pinkett Smith and Foxx taxicab scenes from Collateral and the James Caan-Tuesday Weld stuff in Thief hinted at Mann's sensitivity in the area, but too often (Heat, Ali) he's fumbled it. Countless "action-dramas" fatuously inject sex and a "love interest" seemingly out of contractual obligation (Matt Damon and Franka Potente from the Bourne movies are a particularly no-pulse example), so it's a relief when intimacy is granted more than afterthought status. And so an affair as passionate and electrifying as that of Det. Crockett (Colin Farrell) and Isabella (Gong Li) in Miami Vice is nothing short of a miracle. It's completely ill-advised; he's the undercover cop trying to implode the villainous drug cartel presided over by her husband—the same sleeping-with-the-enemy trope that Tubbs fulfilled in several of the TV episodes, handled infinitely more maturely here. The pair's impromptu mid-film boat trip to Havana in search of great mojitos is Vice’s heart and soul, as Crockett's brooding sadness succumbs to Isabella's sophisticated smirk. A night of tango (Her: "Do you dance?" Him: "I dance"), leads later to torrid sex, made tangible by the subtle tear streak now drying off the side of Isabella's right eye. Writing in the Village Voice, Scott Foundas wrote that the sequence "single-handedly restores mature adult sexuality to Hollywood movies," and one hopes he's not off-base. By the end of their brief detour, they've even come so far as to acknowledge their affair's imminent end, framing the Cuba idyll as its own miniature movie-within-movie.

A long way from the Phone Booth and Daredevil (remember his Bullseye?) Irish badboy who came across as such a shallow chainsmoking douche in interviews, Farrell has nearly redeemed himself in full with his mesmeric (if a touch sleepy) performances in The New World and now Miami Vice. Crockett's a better fit for the distinctly 21st-century hard-partying, slut-banging actor, who seems to have been made to sport the gigolo cop's sockless shoes, sports coat over t-shirt, and lion's mane and mustache (strikingly similar to Jon Voight's look in Heat, minus the facial scarring). Speaking his dialogue in the same halted grunt as Heath Ledger in Brokeback Mountain, Farrell effortlessly exudes the broken-down dejection of a life steeped in violence. He's a distant conversationalist, preferring regretful stares into distant Miami over eye contact. When combined with the occasional bum Mann one-liner ("You cannot negotiate with gravity"), his aloof macho reverie can border on the parodic, but his cool posturing typically smudges right into the canvas of Mann's milieu. Foxx isn't as bold as Farrell—he's content to coast on his own natural humor and charisma, as he did appealingly in the otherwise terrible Any Given Sunday—and by the end Tubbs feels relegated to sidekick status.

In his dogged insistence to avoid a retro-kitsch recycle job (most people think of the old show ironically in terms of anachronistic pastel couture), Mann tips the scales with brute grit. DP Dion Beebe's hi-def digital visuals have the odd quality of desentimentalizing the glittering Miami land and seascapes while casting them in a new, also-beautiful light. The loud closeness of the gunplay scenes are cold and unsteady—the anti-kitsch. The disorienting opening nightclub scene is strictly business, a statement of purpose, and it mimics a great set piece from Collateral (also lensed by Beebe), an interesting minor Mann that now seems like a warm-up for some of Vice's stylistic triumphs. Gone is the TV show's camp humor (Don Johnson's Crockett had a gator on his boat named Elvis who mischievously ate all of his Buddy Holly records), replaced not by humorlessness, but by tossed-off, slick-under-pressure flashes from Foxx and co-villain Luis Tosar (playing a character named Arcángel de Jesús Montoya, proof enough that fun is indeed being had). Other updates, like the soundtrack's Audioslave songs and the closing Nonpoint cover of "In the Air Tonight"—the Phil Collins original was a highlight of the pilot episode—are less welcome, but then so is the state of modern radio rock, and two tastefully placed Mogwai tracks go some way towards making up the difference.

Faced with what Miami Vice is—a lovingly conceived and distinctly Mann-made auteur film that appeared in multiplexes at the height of summer blockbuster season—it's tempting to rehash the old horse about "its flaws are its virtues!" And I'm willing to do exactly that, excepting the movie's disappointing reliance, twice, on unpleasant and garish "women in peril" plot devices, barely made up for by one female cop's own Dirty Harry moment. Such lapses in taste scarcely discount the film's main triumph, that something so video-grainy, big, and expensive could be so beautiful, personal, and rich.