Bringing It Back:

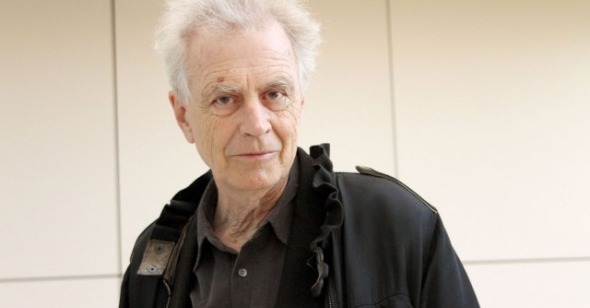

An Interview with Thom Andersen about Los Angeles Plays Itself

by Andrew Tracy

Reverse Shot: Los Angeles Plays Itself originally arose from an idea you had for an illustrative lecture. Was the film in any way shaped by the way you teach, by your methods and sources?

Thom Andersen: I taught some classes at Cal Arts, which do depend on showing excerpts from films. I taught one class on screenwriting, and one on Gilles Deleuzeâs cinema book, which influenced this movie in a certain sense in that what I say about neorealism, the way I privilege the idea of neorealism, was influenced by Deleuzeâs treatment of it. One thing that struck me in relation to that was how Haile Gerimaâs Bush Mama (1979) was such a perfect exemplar of Deleuzeâs ideas about neorealism, about how neorealism was not simply a matter of photographing life as it evolved, but also opened up cinema to what he calls the âtime-imageââthat is, an image in which memory is controlling the movements of the image.

RS: You speak about myths quite often in the film, the âsecret historiesâ of Chinatown (1974), L.A. Confidential (1997) and even Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1989), all of which youâre fairly disparaging about, at least on an ideological level. But there are other myths you refer to positively, especially the âlost Edenâ idea in films like Warholâs Tarzan and Jane Regained. . . Sort Of (1964), Maya Derenâs Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) and Fred Halstedâs âgay porn masterpieceâ L.A. Plays Itself (1972). What makes these âgoodâ myths in your eyes, unlike the first group?

Andersen: Let me start with an anecdote, if I could. A week or two ago, UCLA was running six programs of films about Los Angeles, inspired by my movie. In one program, they showed Cisco Pike (1972), which was made by an old friend of mine, Bill Norton. It was Kris Kristoffersonâs first film, heâs this down-and-out folk singer who gets into selling marijuana. After the screening, a friend of mine said âLos Angeles looks like it was a lot more fun in those days.â I said âIt was.â Iâm not sure thatâs true, but thatâs how I feel. Itâs changed a lot since then, for better or worse. But there was back then, in the late Sixties and early Seventies, more of an interplay between city and country then there is today, and I think that was one of the attractions of the city throughout the first two-thirds, three-fourths of the 20th century. It was a city that was very much in touch with nature, with the mountains, with the landscape, the ocean. Now thatâs become much more the privilege of the upper classes, itâs less accessible to most people. So when I talk about Warholâs movie, or Fred Haldstedâs movie, or Maya Derenâs movie, and how they paint Los Angeles as a kind of countryside, that to me is a mythology that was real.

RS: You think itâs a mythology thatâs more valuable than the one portrayed in Chinatown?

Andersen: Yeah, I think so. One movie that I almost included in the film but didnât was Roger Cormanâs The Wild Angels (1966), because that to me is kind of the definitive statement of the southern California dream, which could only be articulated once there was a sense that it was lost. I think thatâs behind Chinatown too, but when Chinatown tries to articulate what was lost in more concretely political terms, itâs not quite adequate.

In a way, itâs unjust to Chinatown when I say itâs bad history. Because when I reject the historical sense behind the myth of Chinatown, Iâm doing that from a perspective that was made possible by Chinatown, because Chinatown produced a lot of interest in studying the Los Angeles aqueduct, the water project, and that study led to much more nuanced views about Los Angeles and the people of the Owen Valley. So weâre judging Chinatown on the basis of a lot of historical knowledge that wasnât available to Robert Towne when he was writing the script. But on the other hand. . . well, there is this notion that Los Angeles, like many places, was a paradise when it wasnât too populated, and when more people move in, that creates pressures. So, to talk about a kind of paradise on the basis of an under-populated area is a certain kind of . . . I donât know if âelitismâ is the right word, but thereâs something a little false about it.

RS: Chinatown is one of the major turning points you identify in the film, when the realization of the city as a character begun by Wilderâs Double Indemnity (1944) extends to a consciousness of Los Angeles as a historical entity. And it was also one of the high points in this kind of cinema of pessimism, this myth of our supposed helplessness in the face of power. What do you think makes that myth so appealing to us?

Andersen: Let me say one thing in relation to Chinatown. To me, the key line of Los Angeles Plays Itself, which it seems a lot of people havenât picked up on and I havenât talked about, because it is kind of a throwaway, is at the end of the Chinatown section: âAs usual, this is history written by the victors, but a history written in crocodile tears.â What I mean by that is we here in the United Statesâand other countries too, I supposeâcelebrate the losers of history while actually dishonoring their goals and their aspirations. For example, the only person now who has a national holiday named after him in the U.S. is Martin Luther King, Jr., and yet itâs his enemies who are running the country. People like Trent Lott, or William Rehnquist, who started his career in the Goldwater campaign in 1964 by trying to discourage black voters in Arizona from voting. Now in the U.S. thereâs a stamp with Paul Robesonâs picture on it, although Paul Robeson was probably the most reviled American citizen of the first part of the 20th century. In California, thereâs a state holiday devoted to Cesar Chavez, at a time when all of the gains he won for farm workers have been lost. Their situation now is about the same as when he started out, and thatâs after a period when they were making some significant progress in terms of wages, better health care, the right to organize. Thatâs all been lost, yet we celebrate his life while trampling on everything he tried to accomplish.

RS: So these âsecret historiesâ are a means of burying serious consideration of these issues, of relegating them to the past so that we donât have to deal with their present reality.

Andersen: I think so. A great example in the U.S. is peopleâs attitudes towards the various Indian nations. Just as those were being destroyed, the Indians were being romanticized as a kind of nobler people. It seemed that that kind of romanticizing was necessary for people to reconcile themselves to the total eradication of this culture. If we can put these things in the past and regard them as historical tragedies rather than part of an ongoing struggle, in a way it allows us to maintain the same attitudes that weâre decrying.

RS: I came across this quote by Serge Daney where he says that âthe images are no longer on the side of the dialectical truth of âseeingâ and âshowingâ: they have entirely shifted to the side of promotion and advertising, the side of power.â Much of your movie deals with this very idea of power, of those who control film images and of those who try and fight back.

Andersen: Iâm happy that the work that Iâve done in this movie has led to a rediscovery of some of these movies, like Kent MacKenzieâs The Exiles (1961) and Billy Woodberryâs Bless Their Little Hearts (1984) in particular, and Bush Mama also. Iâm glad Iâve helped people to rediscover these movies, which were always available if people searched, but because they were totally independent, and there was no powerful corporation behind them pushing them, people have lost sight of them.

RS: Similarly, you note in the film how so many movies about Los Angeles tend to exclude people who live there, to render them invisibleânot just minorities, but even those who simply donât work in the entertainment industry.

Andersen: Well, people make films about what they know. When Steve Martin wrote L.A. Story (1991) he was writing about the people he knew and the places he knew. In a way Los Angeles is still a lot of villages grouped together. Martin occupies one village, Robert Altman occupies one village. In The Long Goodbye (1973), Altman used his own house as the house where Sterling Hayden lives. Itâs in whatâs called the Malibu Colony, which is a very exclusive beachfront community.

RS: And yet Altman has always painted himself as the great Hollywood outsider.

Andersen: Yes, well. . .

RS: Is this why you rail against the rampant mythification of Los Angeles, because it conceals so much of the actual living thatâs done there, the actual history it possesses?

Andersen: Itâs true that Los Angeles has always been a city of immigrantsâthatâs kind of a clichĂ©, but it has a certain truth. When you talk to people, you find that no one was born in Los Angeles, everybody who lives there comes from somewhere else, which is maybe why it doesnât have a living history based on collective memory. And I think thatâs particularly true of people in the entertainment industry, they come to Los Angeles from somewhere else and they donât have a sense of the cityâs tradition and the cityâs life. Itâs something that people are just starting to become self-conscious about. In a way, Los Angeles is a city which is entirely defined by touristsâ perceptions, because a lot of the residentsâat least those residents who are influential, who write and direct moviesâare essentially tourists.

RS: In Cinema Scope, you stated that, to you, materialism is a good thing, that thereâs âa kind of primitive, crude truth in literalism that can lead one to, letâs say, more sophisticated truths.â Do you think that these kind of places are Los Angelesâ biggest repository of culture, of a shared history?

Andersen: There are certain places and certain buildings in Los Angeles that have come to represent that for a lot of people. I think in a way itâs maybe a little false. Like Eric Hobsbawm says in his book The Invention of Tradition, often what we think of as age-old traditions are actually fairly recent inventions. People tend to invent tradition after the fact. But they are necessary, and I do respond to them emotionally. Like a restaurant thatâs 100 years old, say. Or the Angels Flight [Los Angelesâs legendary vertical railroad], which by the way just had its 100th anniversary, which passed without observation because of its ignominious fate. After the accident in 2002 when it closed down, it was discovered that it was rebuilt in an irresponsible way, and itâs something thatâs almost been covered up, kind of like people are ashamed of what happened and they donât want to acknowledge it. I think Los Angeles is a city which has a reputation for destroying its own past, but it seems thatâs true of most cities these days.

To mention Hobsbawm againâI was reading his memoirs recently, Interestingâhe talks about a number of cities where heâs lived over the years, Paris, New York, San Francisco, Berlin, Vienna. He says that whereas a city like Paris is no longer a city, he recognizes it as the same city he knew when he was young, because the whole city has been turned into a gigantic gentrified bourgeois ghetto. The U.S. cities, despite the changes that have occurred over the past 50 years, are still recognizable as the same place. But I think whatâs happening in Los Angeles is kind of whatâs happened in Paris. Thatâs kind of the ideal of city planners and developers, thatâs what theyâre trying to do with downtown Los Angeles now, to turn it into a bourgeois ghetto and displace poor people, particularly the Mexican and Central American immigrants.

RS: Of course, thatâs another major theme of your film, the cityâs undeclared war on the underclass, such as the defeat of the public housing initiative in the Fifties or the gutting of the public transportation system.

Andersen: Thatâs another aspect which not everyone recognizes: that sense of the public sphere and its importance. Public transportation has this kind of peculiar position in Los Angeles. Unlike Toronto or New York, these older cities where people of all classes use the public transportation system, in Los Angeles thereâs a sense of taking the bus as an experience of being proletarianized. People are afraid of it. And of course when people have that sense of the public sphere, it begins to decline. Itâs happened not only with public transportation, but with public schools. Again, thereâs a sense of public schools as something you want to avoid if you aspire to a certain status in life.

RS: I noticed an amusing little parallel in the film. You devote a large section to Hollywoodâs desecration of Los Angelesâs great modernist architecture, over which you express great horrorâand then later you confess to a vicarious delight in watching the scene in The Terminator (1984) where Schwarzenegger massacres a station full of cops.

Andersen: Yeah, I hope people donât laugh at it.

RS: It is kind of funny.

Andersen: I thought so.

RS: You talk about the police a lot in the film, especially in the section on L.A. Confidential, where you note that the cops didnât control the rackets, they controlled the city. What were some of the most prominent centers of power in Los Angeles? I gather the cops have been a fairly oppressive presence throughout the cityâs history.

Andersen: Yeah, for me and for a lot of people they were. One police chief, I canât remember which one, was asked if he wanted to run for mayor, and he said âNo, that would be a step down.â The center of power represented by the Los Angeles Times has been important as well, although I think people today probably give it too much importance, because now that the Times has become the only area-wide newspaper, people forget that it was only one of six competing newspapers in the first half of the 20th century, and not even the one with the largest circulation. There have been various businessmenâs clubs and alliances, and thereâs always been this conflict between downtown interests and suburban interests. So Los Angeles does have these different centers of development and dispersed downtowns, which you can see geographically in these areas, these clusters of high-rise buildings.

RS: Youâve said that seeing L.A. Confidential was the inspiration for your film. Have you read many of James Ellroyâs books? What do you think about his vision of Los Angeles?

Andersen: I think Ellroy is kind of a mythologer. I mean, on the one hand you have Ellroyâs vision of Los Angeles, and on the other hand you have that of D.J. Waldie. Waldie grew up in one of the first post-WWII suburban planned communities, Lakewood, I think. He wrote a memoir, a history called Holy Land. For me, Waldieâs vision is much more true than Ellroyâs, but Ellroyâs is better known and more appealing to people because itâs more sensational, itâs more like a movie. Itâs based on ideas of crime, of transgression, whereas Waldieâs vision is based on everyday life, the way people really live. Itâs not that Ellroyâs vision is false to his own experience, but itâs appealing to people precisely because itâs an exceptional lifeâafter all, most of us donât have the experience of having our mother murdered while weâre in our childhood. So we kind of value the exceptional rather than the normal, but itâs through the normal that we come to understand life better.

RS: In Cinema Scope, you mention that when you first saw The Exiles in the Sixties, you werenât too impressed because you were far more interested in the New Wave, in a more formalist cinema. Now youâve become something of a champion of literalism, of the realities buried in fictions. What kind of cinema do you value today? How have your positions changed over the years?

Andersen: Well, movies have changed also. I think for better or worse Hollywood movies have gotten somewhat formalistic. The movies that I value today do come from a kind of neorealist tradition. Someone like Hou Hsiao-hsien, or KiarostamiâŠ

RS: The Dardennes, maybe?

Andersen: Yeah, I like their movies a lot. Thereâs a line by Roland Barthes which Iâve taken to quoting frequently which kind of sums it up. He says âa little formalism takes us away from life, and a lot of formalism brings us back to it.â Thatâs my ideal these days, I guess.