The Monster Squad:

An Interview with Dash Shaw

By Erik Luers

Cryptozoo

Dir. Dash Shaw and Jane Samborski, U.S., Magnolia Pictures

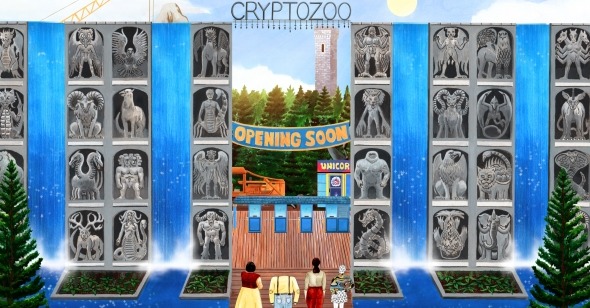

More a sanctuary than an attraction for children, the titular central location of animator Dash Shaw’s second feature, Cryptozoo, is both mythical and mysterious. Housing a collection of cryptids (rare creatures of disputed existence) that would make Michael Crichton envious, the Cryptozoo presents an environment where winged beasts, slithering reptiles, wandering centaurs, insomniac unicorns, and a host of other folkloric creations can live side by side, free from lucrative exploitation.

This being San Francisco in the late 1960s, they’re never completely safe, however. Cryptozoo is set at a moment in time when the U.S. military was getting increasingly involved in the ongoing Vietnam War. Forget Agent Orange; what if cryptids were used as involuntary weaponry? Thwarting the Oval Office’s pursuit at every turn, cryptid activist Lauren Gray seeks to protect the rarest of species: a calming Japanese baku that feasts on bad dreams. As an avatar for the counterculture, this most saintly of cryptids is all about spreading peace and love.

Beautifully co-created by director Shaw and lead animator Jane Samborski, Cryptozoo represents a step forward in the husband-and-wife’s filmmaking pursuits. After their comedy My Entire High School Sinking into the Sea, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2016, this second feature began production in earnest back home in Richmond, Virginia. More serious in tone and expansive in scope, Cryptozoo is endlessly creative in its hand-drawn animation and clever editing flourishes. The voice cast, featuring a murderer’s row of recent American independent cinema mainstays (Lake Bell, Michael Cera, Alex Karpovsky, Louisa Krause, Angeliki Papoulia, Peter Stormare, Grace Zabriskie, and Zoe Kazan), helps ground the more fantastical elements of Shaw’s rather high concept.

Winner of the NEXT Innovator Prize at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, Cryptozoo opens in theaters and On Demand August 20th. A few weeks before the release, I caught up with the writer-director over Zoom to discuss the origins of the project, as well as the intricate details of the painstaking production.

Reverse Shot: You’ve spoken of how the idea for Cryptozoo originated from a personal interest in the 1921 unfinished short The Centaurs by American cartoonist Winsor McCay. To step further back for a moment, I wanted to first ask what McCay’s body of work has meant to your career as an animator. Was he an influential figure for you?

Dash Shaw: He was, yes. If you're interested in animation and comics, Winsor McCay was the godfather of the blending of the two. He was one of the earliest “newspaper comic-strip artists” with his Little Nemo in Slumberland making its debut in the New York Herald in the early 1900s. My father really loved comics and [growing up] I could purchase a Little Nemo in Slumberland collection at Barnes & Noble for five dollars. It’s something about the way those comics were colored that makes them look fantastic still, almost as if they look better as they age. While McCay is often credited with inventing animation, it’s more that he invented the process of crafting key frames that then had an in-betweening stage. That turned out to be a significant invention. It’s a kind of full-animation technique [incorporating twelve to eighteen frames per second] that was pre-Osamu Tezuka.

All of McCay’s projects were about using drawings to show things that photography literally couldn’t. Little Nemo in Slumberland depicts dreams, for example. The dialogue in many of them is, if not pretty difficult, then not very well done. I don’t think that’s controversial for me to say. The joy in those comic strips then comes from the inventive, playful imagery, and distortion of reality that’s inherently dreamlike. McCay’s 1914 animated short Gertie the Dinosaur also takes the obvious “we cannot photograph actual dinosaurs” and recreates dinosaurs through the power of drawing. I eventually saw his unfinished centaur film soon after, and that’s how Cryptozoo was born.

RS: You set Cryptozoo in a very specific place in a very specific time: San Francisco in the late-1960s. Ronald Reagan is governor of California, and the Vietnam War is in progress, facing immense pushback and protest by the counterculture movement. How did the context of the era influence the film’s animation style? In what ways did it complement it?

DS: I know Cryptozoo’s connection to the work of Winsor McCay and to this specific time period might be a little weird, but as I’m practically drawing every single day, my eyes tend to be more attuned to the drawing similarities between things. McCay’s work was considered somewhat of an Art Nouveau-style of drawing, and that style was extremely popular throughout the 1960s, especially due to a renewed interest in the 19th-century illustrator, Aubrey Beardsley. There were reconsiderations of that style taking place throughout the 1960s and so this film [reflects that]. A few years ago, I had been working on a different project—Discipline, an upcoming graphic novel—at The New York Public Library, and one of the other fellows there was researching 1960s counterculture newspapers from around the world. He’d spend an afternoon looking at a free weekly newspaper from Brazil in 1967 and cross-checking it with one from the very same week in Chicago, for example. I would take a look as well and, as a cartoonist, I noticed a similar line quality that was attached to each of them, as well as a specific ideology that was more global and “pre-Internet.” There was a fantasy art-ish look attached to very real ideals, if you will, and the optimism of these publications was obvious. The titles would often be one word, like “PROGRESS,” and they would have something that looked like an Alphonse Mucha painting on the cover.

The touching thing about reading so many of those old magazines today is that we know how everything turned out. Cryptozoo takes that idea and, like Jurassic Park, presents it as something you know is going to fail. A Cryptozoo—or a dinosaur park—can’t work out! The film groups that understanding with the ideals of the 1960s, and the movie is less about what’s going to happen than how it’s going to happen. I thought that might make for an interesting dynamic. As opposed to a traditional fantasy movie where I'm inventing all the creatures from scratch, not only is the film set in a real time and place, but these mythological beings are “real” in that they’re derived from actual mythologies. They were real beings and stories that have been hammered out throughout the passage of time. You can find drawings of the baku in Katsushika Hokusai's work from hundreds of years ago.

RS: Before the title card, you open the film with an extended sequence that’s a bit mysterious and horrific in what’s depicted onscreen. A character is killed off in a gruesome way, and I was wondering if, in your planning stages of how to introduce us to the Cryptozoo, there were specific elements of genre you wanted to incorporate.

DS: Well, the first thing I came up with were the three lead characters of Joan, Lauren, and Phoebe and the goals of each for the Cryptozoo itself (and their relationships/backstories to the fantasy world of the film). The first thing I settled on was that one character’s relationship to the cryptids would be rooted in her past, a “love of creature,” which I think is true for many people. Another character would have a weird kind of mothering of the cryptids, and the third character would be a cryptid herself, who sees the Cryptozoo as an opportunity to be progressive down the line. However, once I had established those three characters and how their conversations could serve as the center of the movie, I realized that, as an audience member, you couldn’t really enter the story through any of them! That’s when I came up with the opening scene of two people stumbling across the Cryptozoo. They're the “norm” of the movie, some stoner, hippie kids who experience that Lovecraftian type thing of encountering a being that's totally beyond you. I felt that would be the best way to start the movie.

I never thought of the opening as resembling a horror film. I know that characters having sex in the woods is a horror movie trope, but I also feel like their being nude in a strange environment also resembles Adam and Eve a bit. It also allowed me the opportunity to do some figure drawing, somewhat similar to Chester Brown’s comic Paying for It, where characters are having sex in a very black environment, almost as if they’re floating in a void.

RS: As you’re writing the script, are you already visualizing the type of animation you’re hoping to incorporate? Or do you begin with an agreed upon style of animation and then begin writing the screenplay? Or are all of these processes happening simultaneously?

DS: When I began making films, my favorite influence was and still is Hayao Miyazaki, a filmmaker who famously doesn’t focus on a script. He just storyboards everything and then begins production based on those storyboards. As a cartoonist, I thought his process made total sense, as storyboards provide their own built-in visual language. However, I found out pretty quickly that that approach wouldn’t work for me on a practical level.

RS: Why not?

DS: You need a script to show to potential collaborators to get them psyched about the movie. They could be actors, producers, etc. and they all want to see some form of script documentation before agreeing to participate. I then spent many years learning how to write scripts and read scripts, eventually participating in the Sundance Directors Lab in 2010. I realized that the script is a hype document. You’re trying to find specific word choices that get people excited, and that can prove quite difficult, especially since the drawings I enjoy are often very difficult to put into words. That’s what I like about them!

RS: It’s interesting to hear you say that, as filmmakers are often asked to provide a “look book” for potential investors, essentially a grab-bag collage of images inspired by the mood of the script.

DS: Jane and I are married and, between My Entire High School Sinking into the Sea and Cryptozoo, she became much more involved and excited about participating in these projects. One of the first things I wanted to accomplish on Cryptozoo was writing something that Jane would enjoy working on. As she had recently participated in an all-women’s Dungeons & Dragons group, I was inspired to create the primarily female cast of Cryptozoo and to have most of the cryptids be things she would enjoy painting.

But from the script to the storyboards, everything became a kind of division of labor where the production morphed into a giant spreadsheet.

With Cryptozoo, we were able to work off of fewer but better drawings. We would make a strong profile painting that could be used throughout the movie. Jane figured out an organizational process that allowed for that kind of reuse and she really has an organizational mind that I don't have. We’ve realized that about each other, and so Jane cut me off from participating! We work off of separate computers, as my computer is very disorganized compared to hers, and when it came time to have our interns scan [the drawings], I told them, “Just listen to Jane. Don’t go off of anything on my computer.”

RS: What’s your workflow like with your editor, Lance Edmands? He’s an accomplished filmmaker in his own right, and I was curious what your conversations are like.

DS: Jane first makes exports of our footage and then sends them off to Lance. I then meet with him and our other editor, Alex Abrahams. Lance and Alex are, first and foremost, looking at the material for story purposes, not knowing how hard it may have been to paint certain things. That distance and separation is good, as they can then feel free to cut things that I would be too scared to cut. I act as a mediator between them and Jane in case they ever have specific requests or questions moving forward. It’s quite hard to draw something coming towards or away from the camera because you’re having to constantly scale things out and figure out proportional changes. Since I already know this, I tend to have things go from left to right when I storyboard a scene, where the proportions are not changing (this is also how information is often communicated in video games and limited animation). As a result, what I send to Lance and Alex to work with isn’t exactly cinema. They are still images, things that look like video game play-throughs. Luckily, Lance and Alex are “film people,” much more than I am, and they have the eye to turn these images into more cinematic sequences.

RS: Cryptozoo is also your second experience working with actors. Have you seen your working relationship with actors grow from your first feature to your second, from developing a shorthand to knowing when to step back and allow the performer room to experiment?

DS: Totally, and I hope there's a visible growth between the two films. I wrote My Entire High School Sinking into the Sea without the expectation of working with great actors, as the main joke of the movie is that it’s a disaster movie where people are talking about other minuscule things while danger surrounds them. I felt that that premise could work with non-actors (I also had the majority of the movie drawn before it was cast). On Cryptozoo, I only drew each character after they had been cast, attempting a weird, sideways inspiration from the actors. As I knew that the world of the film would have a remove to it that might not work for some people, I wanted the voice work to be very sincere and not of the goofy variety you hear in most cartoons. One of the first things I told each member of the cast was that I didn’t want the kind of broad, off-putting voice-acting that you hear in most cartoons. I wanted them to find the human element in their characters and have that shine through a very artificial world.

RS: Earlier you mentioned Discipline, your next animated novel that’s being released in October. While that narrative is also a period piece (set during the American Civil War), I was curious as to how you identify the specific medium best suited to tell a specific story.

DS: Discipline is a story about Quakers and, at the risk of sounding too obvious, so much of Quakerism involves silence. If you're raised as a Quaker, you have the experience of having been a four-year-old who can sit in silence for an hour every week and you end up having a different relationship to silence than most other four-year-olds. Of course, something that’s wonderful about comics is that they don't make any sounds. The book is in black and white, and I really tried to incorporate negative space throughout, as that activates the contrast. There also aren’t any panel borders in the book and that too is in line with illustrations from the Civil War era that didn’t include panel borders. Everything is somewhat floating in a negative space. Each of these traits made the story feel more like a comic book to me than a feature film.

Regarding the films I’ve made thus far, I think of both of my movies as blockbuster movies or action movies, and my books aren’t like that at all. I’ve been trying to make these films for so long that, even as a teenager who enjoyed independent cinema and Pop Art, I always wanted to make an art film that was an action film, something in between an experimental movie and a spectacle movie. I wanted to make big “small movies,” lo-fi blockbusters. When I attended the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in Manhattan, I worked at the SVA Film Library in the early 2000s, and that’s where I received much of my proper film education. I remember Todd Haynes’s 1991 film Poison, a movie that had collage elements with sections that felt like a horror film and sections that played more like a documentary. It was able to be a number of things, and that was inspiring to me as a student. I’ve wanted to make a blockbuster art movie, and that’s something I’ve always kept in my head.