That Most Important Thing

Kelley Dong on Let the Summer Never Come Again

Georgian filmmaker Alexandre Koberidze’s Let the Summer Never Come Again begins with an epigraph superimposed onto a country road. “Love has no end—a story always has. You will now see: a lovestory.” By uniting the two words, Koberidze’s debut feature strives not to reconcile the binary but to delineate their difference. The result is a beguiling, self-reflexive experiment: If “love” and “narrative” are of separate worlds, then what is a “lovestory” and how can it be told? Deeming love the immaterial variable, Koberidze opts to eliminate its appearance—its sights and sounds—from his three and a half hours altogether.

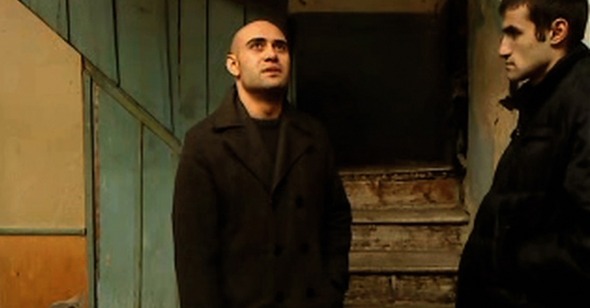

In three chapters of scant detail, the voice of an omniscient woman strings together the fragments of a short love affair. An aspiring dancer (Mate Kevlishvili) leaves his village for the city of Tbilisi, Georgia. But the audition has been cancelled. The man turns to working multiple jobs, from underground fighting to prostitution, and abandons his dreams of dancing. But the monotony of this new life is interrupted by love, which may have no end but always starts with an encounter. After several chance meetings, a handsome military officer (Giorgi Bochorishvili) offers a large sum of money in exchange for the young man’s company. The narrator informs us that the officer, handsome and educated, is the one “in whom the young man has fallen in love.” But it is an invisible and secret fall. The men themselves are stoic and a bit stiff, standing at a distance from one another and the world.

Here is where Let the Summer Never Come Again becomes, for its viewers, an exercise of faith. With not a surreptitious glance to see or whisper to hear, the film deprives audiences of the cues on which we so often depend as proof of intimacy. We see the entering and exiting of different spaces—hotel rooms, the sea, the woods—but never what occurs behind closed doors. Words are exchanged at low volume, obscured by the noise of the city. There are two dimensions to this act of removal. The first is that of privacy’s role in queer relationships as a means of survival, to protect love from outside hostilities. The second is the idea that love does not need cinematic representations to prove its existence. The film’s lack thereof challenges audiences to choose to believe—that love is true, that it is real—regardless of what can or cannot be perceived by the senses.

Between the ebb and flow of invisible romance, the narrator draws our attention to a number of happenings in Tbilisi. The city is not a space but a stage. Recorded at a distance, the performances of Tbilisi’s pedestrians—seemingly unaware of the camera’s surveillance—are surreal and affected but not, as sociologist Erving Goffman would argue, out of a need to impress the public. These moments unfold aimlessly according to a predestined path—a tale of Koberidze’s making. A man purchases a watermelon and hollows it out with a spoon, hides a gun inside it, then robs a bank. A woman falls ill in the park; confused bystanders scramble to call an ambulance. Sometimes these paths overlap with that of the lovers, but their secret remains well kept. When two robbers dressed as clowns mug the officer, his only response is “Fucking clowns.” While he washes the blood from his mouth, the concern on his face prompts one to wonder where he has come from, or to whom he is headed.

The most notable conceit of the film is its use of a Sony Ericsson cellphone, which records video at 15 frames per second with 3.15 megapixels, both nearly five times less than that of the latest smartphones. The phone’s camera produces footage we might refer to as low quality, based on the slow speed at which its pixels adapt to changes in light. But through these oversaturated, auto-exposed, and coarsely textured images, Let the Summer Never Come Again makes visible the mechanisms of its fiction. The pixels are a mere signifier of reality, contingent on the rules set by the phone’s hardware. Even in its most static state, the film appears as if in constant flux. The sky glistens and the sidewalks glitch, their distorted colors reconfiguring in response to the bodies of indistinct passersby. For a moment, the Ericsson even provides an incidentally erotic touch: in isolation, the men eat fruit together on a balcony, glowing orange in the sun. In daylight, the shops seem to melt into one another. By night, the moving cars and lit windows resemble the melting squares of painter Paul Klee, who himself distinguished his shapes as pictorial abstractions, distinct and distant from the real objects to which they referred.

Parts of Let the Summer Never Come Again were also shot on the RED camera. At the beginning of each chapter, an anonymous man stands by a projector, his face out of sight. He loads and rolls the same reel of film, repeating the refrain: "Two days after the war had broken out, I understood that the war hadn't broken out two days ago." He then recalls a childhood memory that involves the stench of rotting butter and hiding from incoming Russian tanks. The repetition of the scene three times over, and the rhythm of winding reels, renders memory a story-making machine. But the introduction of war invites a more difficult challenge. If war has an ending, then is it also a story? Can love stay true, even in the face of war? Abruptly, the officer is sent to Afghanistan for 18 months. The young man returns to the village by train, presumably without a trace. After the men part ways, the narrator does not speak of the romance again.

Summer turns to fall. The young man’s train passes by nameless faces and stops at a station, its location unclear. Of love and story, we have already been told that only love will remain, so the film’s end—accompanied by the classic onscreen title “The End”—is in no way a trick. The men will continue to love beyond the narrative’s reach; how that love will unfold is unnecessary to know. Although it may appear convoluted by description, Koberdize’s film does not play games or engage in twists and turns. One might argue that the messiness of love is necessary to document as an artifact of human recklessness. Without these, Let the Summer Never Come Again gracefully strips love down to the fact that it starts and persists. There are countless questions regarding love and narrative, love and cinema, love and cinema and war. Asking them often becomes a poetics unto itself. But Koberidze has taken a grand step in form, forward and out of the cave, and it seems he has arrived at his answer.

Let the Summer Never Come Again played Saturday, January 13, as part of Museum of the Moving Image’s First Look 2018.