Every Halloween, we present a week’s worth of perfect holiday programming.

First Night:

Isle of the Dead

Imagine you’re alone right now, though you likely are. But imagine you’re alone in a dimly lit room and directly before you, close enough to touch, is a deep, dark, cavernous hole with no discernible back. The darkness could go on forever for all you can perceive. Anything could be concealed in those profound shadows, waiting to catch a glint of light, invade the space and then your nightmares. When a shape makes itself perceptible, it could be a claw, a knife, or, perhaps worst of all, a face—it might not be monstrous, it might not be ugly, but it is surely unfriendly. You have no control over when it will appear or what it will do. It can’t physically hurt you, but it can leech onto your mind, the tenderest part of you. Once you see it, it finds you, and you can never let it go. It’s a curse. Strangely, we have voluntarily approached this terrible place, and are willingly giving ourselves over to it.

This is basically what it’s like to watch a horror movie. Perhaps more than any other genre, horror is about waiting. Submitting to a horror movie is an expression of our strangest, but most human, selves. We are a bundle of nerves, and we want someone, something to just come along and shred them. So we wait. The proximity of death has something to do with its thrill: whether we are being confronted by a person long dead or identifying with one about to die, often in a disturbing or gruesome manner, in films we are only reminded of our mortal coil and how quickly it can be shuffled off.

Why am I this willing victim?

I recently wondered this when watching 1945’s Isle of the Dead. I had never seen it, even though it was a film from the great B-movie producer-auteur Val Lewton and director Mark Robson, who previously collaborated on The Seventh Victim, my choice as the best horror movie of the forties. Perhaps I’d subconsciously held out on watching Isle of the Dead—which Martin Scorsese has ranked as one of the films that scares him the most—because I want there to always be a Lewton film I haven’t yet seen, like a creature huddled somewhere in the back of the closet, waiting for me to dare open the door and uncover it. (Sigh, at least there’s still The Ghost Ship.) Having been conditioned by a string of Lewton films such as Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, The Leopard Man, and The Seventh Victim—all of which came chronologically before this one—I expected a particular formula: namely a certain number of chilling, heart-in-throat set pieces nicely spaced out through the narrative en route to a slightly underwhelming but not momentum-killing denouement. (Victim deviates from this by saving its most frightening scene for an extended climax, and immediately following it with a singularly disquieting, brief last scene.) But the slow-building Isle of the Dead is quite unlike any of them in this and other ways; for the first forty-five minutes of this seventy-two-minute film, I wondered as I was reclining on the couch alone if it could be fairly called a horror movie at all.

The first of the films Lewton made with star Boris Karloff (even though it was finished and released after their 1945 film The Body Snatcher due to production delays and the actor’s health problems), Isle of the Dead got its name and inspiration from a series of famous, near identical paintings by Swiss artist Arnold Böcklin. These unsettling symbolist masterworks depict a mysterious graveyard-like fortress jutting out of the water, its stone walls surrounding a tight cluster of tall cypress trees, being approached by a rowboat that is dwarfed by the size of the island, containing a rower and a standing, stoic figure shrouded in white. Its back is to us, its purpose in making this trip impossible to discern. Is he or she going to the island to mourn a death? Or to be buried?

There is a potential Greek mythological aspect to the painting (it has been interpreted by some as an image of Charon transporting a soul to the underworld), and sure enough, the film Isle of the Dead takes place in Greece, just following the country’s involvement in the Balkan wars of 1912. The fighting is done, and Greece is victorious, but pestilence has broken out. In this decaying, immediately postwar atmosphere, the cruel, hardened General Pherides (Karloff) rules with an iron fist: in the opening scene he wordlessly orders the death of a colonel for allowing his company to arrive late at (an ultimately successful) battle, a command that is carried out under the guise of the colonel’s honorable suicide—not for nothing is the first image of the film a close-up of Pherides washing his hands. Soon, Pherides, accompanied by an American war reporter, decides to pay a visit to a nearby island where his wife is buried. Before they set sail (in a scene borrowed by Scorsese for the beginning of Shutter Island), we get our first glimpse of the ominous looking place, and it’s nothing less than a perfect matte replica of Böcklin’s painting, a strong sign that we’re about to enter a realm of the unreal.

Once there, Pherides discovers to his horror that his beloved’s coffin has been destroyed and emptied. In most other films this would be an integral point and set the main plot in motion, yet here it only serves as a disturbance, albeit one that defines the mood for a film about the specter of death, no matter what looming form it takes. Upset by their discovery, Pherides moves along to the island’s seeming only residence, a house run by a Swiss archaeologist, drawn there by the distant, mysterious sound of a female voice singing. One of the house’s many guests, a British salesman, has come down with an illness, which they soon discover is plague. Because of this, the rest of the people on this island—including St. Aubyn, a British consul; his invalid wife, Mary; her headstrong caretaker, Thea (Ellen Drew), who despises Pherides for his fearsome military reputation; and Kyra, a superstitious housekeeper who seems to have crawled here directly out of the middle ages—are soon quarantined. The remainder of the film necessarily takes place in this shadowy house and its environs, as Pherides grows frighteningly dangerous, deranged by paranoia and buying into Kyra’s terrified beliefs that a nightmarish demon of folklore called a “varvoloka” is lurking here in human form.

War film? Plague melodrama? Supernatural folk tale? Zombie nightmare? Isle of the Dead is an elegant shape-shifter, leaving the audience unaware what the danger is and where it can come from. Up to this point the film is as quietly ambitious and dreamily poetic as other Lewton productions, summoning exquisite, eerie dread in its every breath . . . yet what was it that so terrified Scorsese? The answers come fast and furious in the film’s last third, which involves, in order of appearance, premature burial, sleepwalking, gruesome stabbings, and a nasty plunge off the side of a cliff. All of these occur onscreen as calmly and lyrically as all that came before, making the whole experience quite uncanny.

As in The Seventh Victim, the film’s fears are inextricable from its characters’ existential melancholy: Pherides’s madness partly stems from the fact that he can’t outrun death despite believing that, as a war general, he could save people from it. But in a twist, Karloff’s imperious Pherides isn’t the film’s major heavy. The seemingly benign Mary (played by a mesmerizing Katherine Emery) turns out to be its true vessel for horror. A sick woman prone to paralyzing trance-like states and thus haunted by nightmares of being buried alive, she absorbs all of the film’s fears and then, in the last act of the film, refracts them back at the audience. Isle of the Dead makes you wait, but it repays—or punishes—you by finally showing you the void.

These images in the dark may never leave you: An abandoned coffin. The echoing sound of water drip-drip-dropping on its wooden cover. A blood-curdling scream. Here they are, then, the moments we’ve all been waiting for. In the genuinely hair-raising extended climax, all lines are blurred: between victim and tormenter, reality and fantasy, life and death. The film reminds us that these matters are all about how we perceive them, which is the scariest realization of all. —MK

Second Night:

Twilight Zone: the Movie

“You want to see something really scary?” It’s the question every horror film implicitly asks its audience, but it’s asked explicitly during the prologue of the cursed 1983 omnibus feature Twilight Zone: the Movie. We might not take the invitation particularly seriously, coming as it does from the mouth of that eternally benign prankster Dan Aykroyd. And surely nothing bad can happen to the addressee, none other than Albert Brooks, who seems protected by a strong coat of irony when he responds, “Go ahead, scare me.” His comedy persona can’t save him, however, from what happens next.

This unsettling bit of counterintuitive casting was a brilliant stroke on the part of John Landis—who had only two years earlier given the world An American Werewolf in London, still perhaps mainstream American moviemaking’s most successful melding of comedy and horror. It’s an effective little opener: Aykroyd and Brooks share a car driving down a winding, desolate mountain road in the dead of night. The former appears to have been a hitchhiker, as they don’t know each other well. Nevertheless they are at first enjoying each other’s company as they jovially sing along to Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Midnight Special.” Then the deck eats the tape; there is no radio signal so they must instead entertain each other. They begin to challenge one another with radio theme song trivia (Sea Hunt! National Geographic!), eventually getting to Twilight Zone, reminiscing and singing its praises. Ah, this is just an innocuous little intro, soon to transition into the main program, into Rod Serling’s realm, that “land of shadow and substance, of things and ideas . . .” Well, yes, but Landis has one great scare first.

Discussion of this movie never starts here, of course. The first section, directed by Landis, is the feature’s unfortunate eternal claim to fame, as its production was halted by what is probably the worst on-set tragedy in Hollywood history: in a scene taking place during the Vietnam war, star Vic Morrow and two young children, Myca Dinh Le and Renee Shin-Yi Chen, were killed by a poorly supervised, low-hovering helicopter, Morrow and Le decapitated. The true-life horror resulted in terrible scandal, plaguing not only the film but the filmmakers involved, especially Landis, whose reputation, then on the ascendant after Animal House, The Blues Brothers, and Werewolf in London, was never the same again; and it made the movie forever a wary object of disaffection. Yet I’m not writing about it today to talk about the Landis segment, a tale of a horrible racist getting his comeuppance oddly patched together from canned footage; nor do I wish to deal with Steven Spielberg’s treacly tale about white nursing-home residents who learn valuable life lessons from Scatman Crothers’s magical Negro figure; and I couldn’t care less about George Miller’s insufferably histrionic remake of the classic William Shatner–starring “Nightmare at 30,000 Feet” episode, with a bug-eyed John Lithgow seeing a gremlin on the wing of his airplane. No, what makes Twilight Zone: the Movie still something worth reckoning with is Joe Dante’s third entry, a genuinely perverse reimagining of the famous 1961 “It’s a Good Life” episode, also subsequently parodied in a Simpsons Treehouse of Horror episode. Hilarious and harrowing in equal measure, Dante’s segment is an effective condensing of the trademark cartoonish horror of his best work, and it scarred many a child of the eighties—this one included—who made the mistake of happening upon it.

The ultimate disappointment of the entire omnibus is that it never really captures what made Twilight Zone so singularly unsettling, indulging instead in the studio excess typical of eighties cinema, whether it be via sentiment or special effects. Dante’s segment is guilty of the latter, but the animatronics and camera tricks are deployed in favor of something so idiosyncratic and strange that it becomes its own auteurist thing rather than a slavish homage. In this story, which Dante made one year before his career-defining piece of cartoon horror, Gremlins, Helen Foley, played by a fresh-faced Kathleen Quinlan, makes friends with a seemingly sweet cherub named Anthony (Jeremy Licht), after accidentally backing over him in the parking lot of a roadside diner and nearly killing him. His bike a twisted mess, she gives him a ride home. It’s his birthday, he claims, but no one cares. When they arrive at his house, a perfectly garish Chuck Jones–style Victorian, it seems, however, that the family does care—a little too much. A dimple-cheeked, round-faced mother eternally in an apron; a benevolent father with an argyle sweater; a teenage sister in a schoolgirl uniform; an appealingly disheveled uncle. They’re all perfect, like they walked right out of a catalogue or a 1950s family sitcom. But aren’t their smiles a little too broad? Their welcoming of Helen a little intense? Their need to please Anthony a little too desperate?

If their plastered grins don’t clue you in that something is exceedingly wrong here, then the set design will: couches, chairs, and lamps that are overly rounded, scrubbed too clean; framed drawings of moms, dads, and kids with faces literally erased; televisions blaring classic cartoons in seemingly every corner; rooms with different color schemes, including one shadowy upstairs hallway of German expressionist black and white, against which Anthony’s red plaid shirt looks like a smear of blood. This is clearly a child’s—or a cartoonist’s—idea of a house, and it grows increasingly disturbing to Helen. Then, the first true nightmare: from a bedroom doorway we see the back of a scraggly blonde girl in pajamas looking at a television, her face nearly pressed up against the glass. “That’s Sarah, my other sister. She was in an accident,” Anthony says, then walks Helen away. Cut to a front view of Sarah. At first we just see her eyes darting back and forth as she watches some old animated short, then the camera rises and we see the result of this “accident”: she has no mouth—just a clean patch of unblemished skin.

It doesn’t take long after this to get the idea: Anthony has supernatural powers, can get whatever he wants when he wishes it, and thus rules this house—his world—with capricious evil, violently punishing those who disappoint him. The family in this house is not a real family, but a bunch of randomly assembled prisoners (with Helen being the potential latest), forced to play their roles with aplomb, as though guns are pressed to their heads. “Maybe he’ll do to you what he did to his real mother and father,” his “sister” says at one point, intimating something too horrible for us to ever know.

Serling’s original idea for this was a brilliant one, implying that all the cruel dictators of this world are essentially children screaming from their cribs, wanting attention, craving satisfaction. Dante turns Serling’s political point into something more extravagant, grotesque, and pointedly American: a kid’s mind twisted by overexposure to television. He isn’t just cruel, he needs constant stimulation. Dante’s greatest expression of this is a literal hat trick: he forces “Uncle Walt” (Invasion of the Body Snatchers’ Kevin McCarthy, fabulously terrified while trying to put on a smile) to perform for him, the old rabbit-in-the-hat magic show. We, the family, and Uncle Walt know that anything could be in that hat. The tension is unbearable as he reaches his hand into that dark hole, his face clearly praying that it’s not something profoundly awful. At first, it’s a fluffy white bunny. They all smile and sigh. Relief. Perhaps Anthony is in a good mood. But then something else comes out. And it’s hilarious and it’s horrible and it’s dangerous, but it’s the kind of thing that could only have come from the mind of a child. Or, of course, Joe Dante.—MK

Third Night:

Eyes Without a Face

Why is it that when we talk about what’s scary in horror filmmaking we often talk about things that “shock” as opposed to “haunt” us? Perhaps it’s the immediate visceral kick of the former, and how easy that is to assimilate and reckon with once our aroused nervous systems have calmed down and the lights have gone back up. Perhaps it’s the inherent difficulty in crafting something that creates a lingering unease in the viewer—that which truly haunts is a rare beast. We are haunted by that which we can’t forget, can’t fully understand. And maybe that which haunts exerts its pull because, on some level, we don’t want to escape its thrall. A jolt is explainable: a sound or image entered our perception unexpectedly. With a good haunting, we’re tantalized. Insidious and Sinister are scary. The Spirit of the Beehive and The Uninvited are haunting. Halloween and The Fog are both. Eyes Without a Face has its share of scares, but its overall effect is of the haunting variety.

The film’s director, Georges Franju (cofounder of the legendary Cinémathèque française), felt the story, from a novel by Jean Redon, had an uneasy relation to horror as it’s generally conceived of. He notes: “It’s a quieter mood than horror . . . more internal, more penetrating. It’s horror in homeopathic doses.” Eyes Without a Face doesn’t shock or jolt, and is incredibly quiet throughout. Franju’s shooting is mostly restrained. There are a few moments of gore, a few bits of unexpected violence. Loud dogs howl on the soundtrack from time to time, creating a cacophonous sense of unease that enters and then leaves as quickly as it came. Maurice Jarre’s drunken carnival of a score might be unsettling, but it also flirts with kitsch. The film is mostly muted, driven by characters with often obscure motivations.

Much of the early part of Eyes consists of hushed conversation about things we often don’t understand until much later. We know there is Doctor Génessier (Pierre Brasseur), who, using large dogs for tests, experiments with radical skin grafting procedures at his secluded countryside chateau and is convinced he has just achieved some kind of radical breakthrough. He has an assistant, Louise (Alida Valli), who, in the film’s grabber of an opening, carts a mauled body from a car and dumps it into a river. That body is later identified by the doctor to the police as that of his daughter Christiane, badly injured in a car accident (we learn after some time that the doctor was driving the car), leaving her little more than a pair of eyes without a face some time prior to the film’s open. But when we meet Christiane, alive, sequestered in the Doctor’s remote clinic, Eyes jumps into another, haunting register of the uncanny. With the help of Louise, the Doctor, wracked by guilt over causing the accident, scouts the nearby town for young girls whose faces might just fit over Christiane’s gaping wound, lures them to the facility, and sets about cutting away.

Much of the uneasy effect of the film’s later sequences is due to the presence of Edith Scob (recently revived for symbolic effect in Leos Carax’s Holy Motors), and especially her long, swanlike neck and porcelain skin. As Christiane Génessier, she spends most of the film behind a mask, but both mask and its wearer are so creamily alabaster in black-and-white that it’s hard to tell where one ends and the other begins. She’s often framed facing away from the camera . . . and you’ve probably never thought much about the unease of looking at someone looking away from you until you watch this film (also note all the instances where Franju uses the same device with other actresses). When we are given the chance to look at the mask in close-up, Christiane is subtly overlit, helping to erase the line where her mask meets the skin. The most unsettling element is the frozen ring around the moving, wide human eyes where you can always discern the hint of a shadow filling the separation between skin and mask. Or, come to think of it, is it even more unsettling to hear her voice, muffled and springing from lips that remain unmoving?

There is obvious tension created here: what’s behind that mask? And before we see the mask, what’s on the other side of that head of luscious, shiny hair? Once we know Christiane’s tale we wonder: Will we ever see the true horror of her disfigurement? We never really do: Franju only allows a glimpse in an out-of-focus close-up. What haunts me the most is not this lack of a terrifying reveal; instead, it’s the film’s final frames, in which Christiane, now convinced that her father’s ever more frantic attempts to save her face will always be doomed to failure, ends her isolation within his clinic. She floats into the cavernous space where the Professor’s dogs are locked up and lets them loose, looking like a graceful, frozen-faced ballerina, or perhaps porcelain doll come to life. The animals run wild and maul the Professor, their tormentor. As Christiane exits the compound we see her from behind, ghastly, arms outstretched, nearly shimmering. She’s free, but she is still ever trapped behind a mask, and this is the last time we will see her. This final image, and all the possibilities it portends, lingers, haunts. Where will this poor, tragic disfigured girl go? We’ll never know. —JR

Fourth Night:

Candyman

A couple of years ago in this very space, I wondered if Michael Haneke had filched the supernal opening shot of Funny Games from Georges Sluizer’s The Vanishing, which itself recalled the beginning of The Shining—three memorable bird-of-prey perspectives. So let’s make it a quartet: the credit sequence of Bernard Rose’s 1992 film Candyman fits nicely in this company, tracking serenely above the streets of Chicago to the accompaniment of Philip Glass’s churning choral score. The sensation of flight is fleeting, replaced in short order by more earthbound activities—a percussively edited suburban-legend prologue evoking ‘80s dreck right down to the viciously slashed blonde in a bitsy bra—but it imbues Rose’s chiller with the impression of some higher purpose.

Arriving one year after Wes Craven’s similarly ghetto-gothic The People Under the Stairs, Candyman transposes Clive Barker’s short story “The Forbidden” to a burned out North Side housing block of Cabrini-Green, a predominantly African-American enclave ruled from within by brutal drug dealers. The entry of lily-white grad student Helen (Virginia Madsen) into this closed community stirs up plenty of trouble and subtext for the character and the filmmaker respectively, and there are great, teasing implications to the early scenes: the would-be intellectual cruising through the projects, looking for subjects whose superstitions she can definitively deconstruct in the academic arena. “An entire community starts attributing the daily horrors of their lives to a mythical figure,” she explains confidently to her skeptical (black) research partner Bernadette (Kasi Lemmons, reprising her best pal role from The Silence of the Lambs); the idea of an outsider in over her head is visualized in a wonderful shot of Helen crawling through a hole in a wall not realizing that it’s also the mouth in a massive graffiti drawing of a black man’s face.

The portrait is the first of several avatars for Candyman, a low-born, high-society artist of post–Civil War vintage who was lynched for impregnating a white woman and whose spirit reportedly haunts the premises of Cabrini-Green. Helen’s thesis about ghost stories as cover for social ills is initially proven right—she meets a gang-banger who goes by the handle Candyman and quite shockingly slugs her in the face with the blunt end of a metal hook—but she also ends up conjuring the genuine article. And just as the victims in the stories she’s recording for posterity seemingly invite their demise at the villain’s (legitimately hooked) hand by saying his name five times in front of a mirror—shades of “Bloody Mary” and also Beetlejuice—Helen seems to want the monster’s appearance at least as much as she fears it, a desire which in turn evokes the primal scene of dangerous miscegenation that started the whole cycle in the first place.

This mixture of lust and terror casts the action in a nicely purplish hue; Rose has the right unabashedly lurid sensibility for Clive Barker, and he doesn’t skimp on the pungent details (urinal stalls caked with feces; Helen’s face hideously swollen in the aftermath of her assault). He’s also a great entertainer in an old-school tradition. Candyman came out right alongside Francis Ford Coppola’s super-deluxe Dracula, and its Guignol is grander; plus, the dynamic between Tony Todd’s suavely menacing title character and his possibly reincarnated twentieth-century inamorata is more hypnotically erotic than Gary Oldman’s mind-fuck seduction of Winona Ryder. (This is also literally true: Madsen has said that Rose actually hypnotized her in between takes to elicit some properly glassy-eyed expressions; Method acting by way of Caligari, or maybe Werner Herzog).

Rose also has great powers of suggestion as a filmmaker (Paperhouse is a uniquely hallucinatory childhood fantasy) and the tension between his poeticism and the pulpy particulars of Barker’s tale—which turns Helen into a scapegoat for Candyman’s spectacularly violent murders and then kills her in a fiery climax—is stretched taut across the various narrative and dramatic clichés. Candyman has enough chunky gore and blunt force shocks to warrant its VHS-generation reputation as a slumber-party staple (complete with the requisite wee-hours dare to decamp to the bathroom and say the magic words with the lights off), but its hothouse atmosphere keeps threatening to blossom into something much lusher. In the end, the script’s racial provocations don’t come to much: Todd’s marvelously understated malevolence can’t quite fill in the blanks of his character’s increasingly muddled motivation, and Helen’s fatal self-sacrifice on behalf of an abducted baby doesn’t achieve the intended gravitas. But the idea that she posthumously adopts the persona of Candy(wo)man is a great sick joke on the notion of solidarity—the heroically martyred woman taking up the mantle of ghoulish Otherness from her killer and using it to slaughter her philandering, mansplaining husband (Xander Berkeley). It makes Candyman that rarest of things: a horror movie with a happy ending. —AN

Fifth Night:

Night of the Demon

Jacques Tourneur’s 1957 Night of the Demon can sit proudly next to the early-forties masterpieces the director made with Val Lewton (Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, The Leopard Man), high praise for any film. There’s a certain black unknowability and alien sensuousness absent in this later model, but Tourneur’s sure-handed signature and its flashes of the old terror are more than enough to bolster arguments for Tourneur’s equal co-authorship with producer-auteur Lewton of whatever made those classics so singular. The film’s kinship with the Lewton films is evident from the first scene, as a car’s headlights slice through trees off some remote English country road, recalling flashlights penetrating gaps in meadow grass in I Walked with a Zombie’s extended chase scenes—and foretelling Mulholland Drive’s nocturnal opening joyride.

The driver is a Professor Harrington (Maurice Denham), who’s in a hurry to beg off a demonic rune cast upon him by a cult leader named Karswell (Niall MacGinnis) in revenge for some slight, and which, since it’s too late to be called off, kills him outside his garage when he gets home. It’s crucial that the film establishes the very real existence of supernatural danger from the jump, so the audience never wholeheartedly sides with the smug rationalism of protagonist Dr. Holden (Dana Andrews), an American in England to help expose Karswell as a fraudster at a convention. Producer Hal E. Chester took this need to establish the demon’s reality too far, insisting on notorious inserts of a shoddy critter costume near the beginning and end of the film. The interference infuriated Tourneur, Andrews, and writer Charles Bennett, who believed that showing the demonic presence as just a distant sphere of smoke with a faintly visible creature inside, accompanied by what sounds like a pail of writhing beetles or a spinning wheel in need of grease, as they did throughout the film, was scarier. The spell-breaking bookends are unfortunate blemishes on a film that earns most of its substantial depths of horror from—as ever in the Lewton pictures and horror in general—the power of suggestion. (Shots of the devil in Rosemary’s Baby a decade later prove that showing the monster can be as frightening as suggesting it, provided the shot is brief enough to be subliminal.)

The instinct to give the demon its star-making close-up was not out of line with the spirit of M. R. James, author of the film’s source material, “Casting the Runes.” The great ghost story writer, medieval scholar, and celebrated King’s College mainstay often allowed for moments when his tales’ lurking horror was made manifest (a slimy hand on the arm, an apparition at the window), though issues of who was perceiving it and in what mental state always made them ambiguous, unlike the omnisciently, objectively presented baddie in Night of the Demon. James’s instances of awful reveals also gain power from the urbane sophistication and carefully, matter-of-factly drawn settings that mark the rest of the story.

Obviously, “not showing” is simpler in literature than film. Jonathan Miller’s justly celebrated 1968 BBC James adaptation Whistle and I’ll Come to You succeeded by pushing the story further into abstraction. Night of the Demon is better appreciated as its own devilish creation rather than in relation to the James story. Its mood of unpleasant menace is sustained through even the more staid stretches of exposition, mostly involving Andrews’s Holden, much like the professor in Whistle, arrogantly trumpeting his unbelief in the irrational, smirking and snorting at supernatural claims, making you long to see his chastening comeuppance. His cynicism is chiseled away at incrementally. It survives an early set piece at a children’s party, at which Karswell, who lives with his mother at an imposing mansion (“I don’t know what his racket is, but it sure pays well!”), entertains kiddies as Bobo the Magnificent, and attempts to intimidate Holden by calling up a violent windstorm. The same scene features one high-volume shock cut to a child's screaming masked face to jolt those dozing, which Karswell follows with a droll, “Oh, how terrifying,” and the mother is all the while a little too enthusiastically offering her homemade ice cream (infused with tannis root?).

Holden clings to his precious logic even as Harrington’s niece Joanna (Peggy Cummins)—a platonic sidekick throughout—points out that all of the little things happening to Holden, such as feeling cold in the heat and getting passed a parchment of runic symbols, presaged her uncle’s mysterious death. Dragged to a séance by Joanna, Holden sits unmoved as the medium (a manic, speaking-in-tongues Reginald Beckwith) channels the spirits and exact voices of a little girl and Prof. Harrington, rudely leaving with a snippy “That stuff is made up!” (Snippets of the séance were memorably sampled in Kate Bush’s “Hounds of Love.”)

It takes a visit to Stonehenge (providing as effective a readymade mysticism here as it does in Polanski’s Tess) to translate his runic symbols, and a wrestle with a housecat-cum-panther (a silly scene, but the callback to The Leopard Man is welcome), to crack Holden’s defenses. After a climactic death seals it, he’s forced to admit to Joanna, “You were right, maybe it’s better not to know.” Andrews, a bit sluggish of face and occasionally slurry-worded, still nails Holden’s American presumptuousness—he’s both punchable and sympathetic—while the bald and goateed MacGinnis summons Charles Laughton in Island of Lost Souls, while avoiding the hamminess the role invites.

Regular Hitchcock collaborator Bennett’s screenplay casts Holden’s championing of reason (as he sees it) as vain folly without it coming across as stupidly anti-intellectual. When confronted with evidence of the “real” hidden world, Holden’s vision blurs, like he’s a newborn adjusting his eyes to the light, looking past “the shadows that can blind men to truth,” in Karswell’s words. In Night of the Demon, superstition is rational, reason foolhardy. The film unsettles because it never flips that paradox back around—the world remains topsy-turvy to the bleak, sinister end. —JS

Sixth Night:

Black Sunday

For a child, one of the most attractive things about horror films is the sense of being given a glimpse of something forbidden. In my youth I was allowed to watch most things on TV, but Hammer House of Horror (a weekly TV compendium of short, bloody stories in the style of Tales from the Crypt) I most certainly was not. This of course meant that I wanted to see Hammer House of Horror more than anything else. It’s arguable that this addictive sense of excitement and guilt, this craving of the taboo, never really leaves us, even as adults. It was there when cinema started (the macabre shadow puppetry played out in secret basement gatherings of French high society and the Fantasmagorie of Emile Cohl) and it is the sensory crucible out of which “exploitation cinema” was established and continues (for better and/or worse) to flourish today.

The Italian cinematographer-turned-director Mario Bava was an expert at titillating, like the later Ken Russell or Paul Verhoeven. Titillation alone was far from the fulcrum of his work—he was an exceptionally gifted visual stylist and a great horror innovator—but his films were nevertheless characterized by a desire to home in on and awaken precisely those things we might have a tendency to repress, lest our parents catch us enjoying them—nudity, violence, sex, blasphemy, gore. It is not a matter of simply including lashings of them (as plenty of horror directors have done) but of doing so in a manner that makes us feel, as an audience, like we’re being watched while we watch. Furthermore Bava would expertly place the audience’s transgressive predilections inside a context of disorienting fear, almost as if it were Pavlovian conditioning therapy. As with so many Italian directors, Catholic guilt certainly had a lot to answer for.

Bava’s Black Sunday (a.k.a. The Mask of Satan)—his solo debut as director—is a paradoxical film in many ways. It was released in 1960 (at the height of one of the most fecund eras in all of cinema, particularly in Europe—in Italy alone, La dolce vita, L’avventura and Rocco and His Brothers were all released that year), and like a lot of Italian examples of genre cinema, it sought (successfully) to push buttons and boundaries, particularly in terms of sex (incest and necrophilia are both invoked). Yet by comparison with two other horror masterpieces released in 1960: Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom and Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho—both cornerstones of modernity within the genre—it feels misleadingly traditional. Very loosely based on a short story by Gogol called “The Vij,” Black Sunday has the immediate feel of a classic gothic Hammer film such as The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) or Horror of Dracula (1958), only it’s as though Terence Fisher has been replaced in the director’s chair by Orson Welles. Bava shows his hand early: in a brutal, sadistic opening, a mask with spikes on the inside is hammered into the face of a beautiful woman, Asa, prior to her execution for witchcraft. Her bare back is also branded with a hot iron. With her last words, she places a curse on her executioner’s entire lineage. Two centuries later, a pair of doctors come across the crypt where Asa is buried and one of them removes her mask, to reveal a half-preserved face, like a broken china doll with its eyes smashed out, overrun with baby scorpions.

Apart from these images—these ideas—and many more in Black Sunday which were legitimately shocking for the time (and which fell afoul of the British censors, who initially refused it even an ‘X’ certificate), the apparent classicism of the film is also subverted by its singular fixation on the physical person of its star, the iconic “scream queen” of Italian film, Barbara Steele. Steele—an English actress who struggled for parts in the UK despite (or on account of?) her striking looks—plays both the witch, Asa, and the princess Katya, one of the cursed descendants. When we first see Asa she is tied to a stake, writhing and defiantly spitting her contempt for her accusers, her formidable beauty and sex appeal well in evidence. When we first see her as Katya, she is standing in the crypt, imperiously accompanied by two enormous, batwing-eared Doberman pinschers—at the time we do not know she is Katya but believe she is Asa resurrected—but as the camera approaches her we see that she is fragile, uncertain, not in control. Bava’s decision to embody good and evil, confidence and fragility in one actress (a very direct treatment of the madonna/whore paradox) allows him to indulge in funny games with his audience’s emotions and desires. Katya’s crucifix, for example, wards off not only the evildoers but also the amorous attentions of her admirer, Gorobec (John Richardson) as he lays her on the bed and accidentally reveals part of her breast (his ardour is momentarily interrupted by the sight of it on her exposed neck). Later we see Steele as Asa, completely naked—in pictorial form—and might catch ourselves wondering a bit too long if the painting in question might actually be of Katya. Toward the end, as Asa (resurrected) starts to draw the lifeblood from Katya in order to prolong her reign of terror, the gasps of pain from the latter begin to resemble gasps of pleasure. It’s the confusion around sex (do we prefer the good kind or the bad?) that is as powerfully seductive as the implication of sex itself, which by today’s standards is relatively tame.

Another seeming contradiction which Bava shows us is nothing of the kind can be found in the relationship between horror and beauty. In England, cinematographer Freddie Francis (the English Bava?) would tread the same territory in shooting The Innocents a year later, but where the horror in Jack Clayton’s film was largely psychological, Bava places genuinely horrific imagery within an ethereal landscape of bewitching cinematic artistry. Aside from Steele’s own elegance (even as the face-punctured Asa, she seduces) the film is composed of some of the most unforgettably exquisite visual moments in the genre: a slow-motion sequence of a carriage driven by a vampire, gliding through the forest to pick up Gorobec is as mesmerizing as the equivalent fast-motion sequence in Murnau’s Nosferatu is risible. Bava’s photographer’s eye for composition (he cut his teeth working with Rossellini, Pabst, Tourneur, and Raoul Walsh) means that not a frame is devoid of detail or interest: like Welles (who used to paint his own props and decorative fittings) Bava was meticulous with production design, cramming tracking shots through corridors of Katya’s castle with ornaments and baubles. Even in black and white, Bava seemed to know how to paint all the colors of darkness. At one point, the entire frame is filled with jagged branches, creating a lurid jigsaw motif, as if the screen could break into pieces. We might occasionally be reminded of the more expressionistic stylings of Jean Epstein’s The Fall of the House of Usher or Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, but whereas Bava’s shocks have a violent directness to them, the most beautiful images in Black Sunday creep up on you.

Bava’s appetite for innovation shows in the key action sequences in Black Sunday, which subvert the rules of horror, as where Asa’s tombstone explodes, leaving her lying prone (as opposed to the conventional “rising from the coffin” shot), or when the vampiric evildoers are defeated with spikes through their eyes instead of their chests. The overall effect is of a fiercely original approach to a pointedly baroque type of story. Bava would adapt Maupassant, Chekhov, and Tolstoy in 1963’s Black Sabbath, a triptych—in color this time—held together by a playful Boris Karloff, which includes an extraordinary Fellini-esque kicker. Having jump-started Italian horror cinema, he would later be credited with spawning the giallo subgenre (detective-horror) which brought us the likes of Lucio Fulci and Dario Argento. While Bava continued to remain true to his gothic roots with the likes of The Whip and the Body and Kill, Baby, Kill, he had given way to more modern auteurs who would take their taboos further than he ever would, culminating in extremities like Ruggero Deodato’s 1978 Cannibal Holocaust.

Black Sunday is all about seduction. It knows it’s being naughty (as do you), but it will never make you feel rotten about it afterwards. For if Bava, Hitchcock, and Powell showed us in 1960 how the sense of the forbidden is an essential ingredient—the spice, if you will—of all good horror cinema, their masterpieces survive to this day because of their artistry and the frightening power of their images. —JA

Seventh Night:

The Babadook

It’s unclear at this point if Australian director Jennifer Kent wants to continue making horror films, but judging by her terrifying and moving debut feature, The Babadook, it’s clear that horror needs her. In what has been a fairly moribund year for the genre (if Only Lovers Left Alive doesn’t count—and it doesn’t—then there’s not much worth mentioning in terms of mainstream releases), Kent’s film stands out sharply in the dark, teeth and fingernails gleaming. That this seemingly simple story of a children’s book monster come to fearsome life is so truly frightening without being overly derivative is in itself a feat; that the film is also an intelligently conceived and surprisingly poignant character drama without sacrificing any of its scares is downright wondrous.

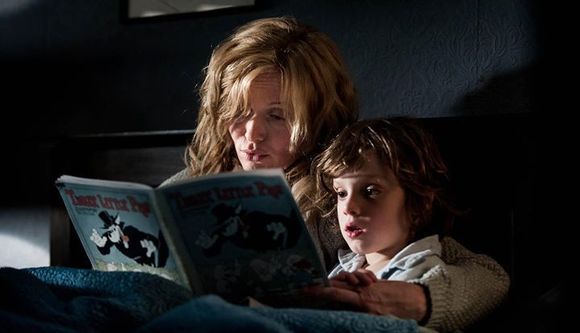

Soon we’ll be able to add the name Essie Davis to the ever-growing list of great, emotionally complex performances that did not receive critical accolades or awards because they dared to be only in a horror film (think Deborah Kerr in The Innocents, Dee Wallace in Cujo, Alison Lohman in Drag Me to Hell—the list goes on and on.). As Amelia, a single mother doing her damndest to take care of her son, Samuel (Noah Wiseman), an angry, increasingly violent problem child, Davis is put through an emotional gauntlet. Her character is still suffering a form of post-traumatic stress over the accidental death of her husband seven years earlier, in a car crash en route to the hospital to give birth to Samuel. As the film begins, Amelia is jolted from a nightmare, although she’s about to be plunged into a much greater, waking one. Kent swiftly establishes a domestic setting filled with anxiety, expressed in quick cutting and claustrophobic spaces. Samuel is driven to protect his mother from the monsters he reads about in storybooks, like the Big Bad Wolf, but his methods for doing so—such as building destructive catapult devices—are not appreciated, either at home or in school. Samuel’s childish intensity is not just boys-will-be-boys behavior, but the crying out to resolve unattended emotional issues at home, and a natural response to the dangerous world outside that home, a world that snatched his father away before he was born.

Matters get exponentially worse when Amelia begins to read to Samuel a mysterious storybook that has appeared on his shelf, titled Mister Babadook. Encased in an anonymous hardcover red binding, and featuring neither author credit nor copyright, the creepy pop-up tale has the simple logic and forward momentum of a classic children’s picture book (think the great Sesame Street–branded The Monster at the End of This Book, with its building, pleading tension), yet with an unsettling abstraction. The book itself—illustrated by Alex Juhasz—is a triumph of prop design; its nefarious title creature, a German expressionist–inspired demon with razor sharp fingers and teeth, is so disquieting in drawing and accompanying text that we cannot blame little Samuel when he breaks down in a screaming and sobbing fit before Amelia can even finish reading it to him. As we all know from the images we remember from childhood—on the page and on the screen, and sometimes in real life—what is seen can never be unseen. And Mister Babadook proves to be inescapable. (“If it’s in a word or in a book, you can’t get rid of the Babadook.”) Yet Kent has not just created a story of a cursed object that latches onto the innocent and unsuspecting, à la Ringu; instead this is a film about a mother and son forced to deal with their lingering trauma, manifest as a shadowy, cardboard demon dead set on destroying them by turning them against each other. Most of The Babadook functions as the scariest family therapy session ever.

“I promise to protect you if you promise to protect me,” Samuel tells his mother at one point. The film is at its most disturbing when it begins to betray the basic, unwritten parent-child contract. What starts off as a skilled entry in the bogeyman genre—in which we and the characters constantly wonder if the thing that’s going bump in the night is real or not—turns into something unexpectedly volatile. The more she tries to “get rid of the Babadook” (by tossing out, tearing, or burning the book), the more it gets inside her, gradually turning her from Samuel’s protector to his unstable stalker, a distaff Jack Torrance. Shivers turn to wallops, as the threat starts to emanate from within and become concrete, physical. Kent’s point is direct and clear and it’s a good one: by repressing the tragedy of her husband’s death years earlier she has allowed a monster to fester and grow in their minds and in their house, and it will now take over and completely destroy her and her child if she doesn’t finally confront it and fight back.

And fight she does, in The Babadook’s Grand Guignol final half hour. But Kent is too clever—and too ruthless—to renege on her premise and promise: even if it can be controlled, this is one beast that perhaps cannot be defeated. —MK