Sundance Film Festival 2021: Dispatch One

By Nicholas Russell

For this year’s virtual incarnation of Sundance, numerous technical innovations tried to recreate the in-person experience: live chat Q&As for premieres, moderated screening introductions featuring directors Zooming from their bedrooms, a variety of indigenous land acknowledgments before every film. There wasn’t as much awkwardness in the form of glitchy, poorly synced Zoom interviews, as one might have expected, though the same can’t be said for the sometimes verbose, overly grave ways that some filmmakers talked about their projects. That seemed to be one of the most salient aspects of this year’s festival: how directors chose to frame their movies. There was a degree of anxiousness that was likely the product of adjusting from speaking to a full auditorium to speaking to a webcam. But even more present was a self-seriousness that hinted at the newer ways diversity and inclusion initiatives throughout the industry have shaped the way people talk about art. Specifically, the self-consciousness that stems from intense scrutiny (often on social media) over who is featured, what demographic they represent, and how long they’re on-screen. So, this year at Sundance, it seemed rare for a movie to be about only one thing. Or, I should say, for a movie to be described as only one thing by its creator.

For example, Rebecca Hall’s directorial debut, Passing, is about...well, it was unclear from her own words what Hall wanted it to be about. During her introduction at the premiere, Hall mentioned her love of the 1929 Nella Larsen novel the film is based on, its intricate themes, its bold sociological statements. “Is it about race?” she asked. “Is it about gender? Is it about sexuality?” The impulse to complicate the accepted idea of what something is is understandable. But this was an odd way to introduce a story that, among other things, is about race. Of course, the novel and the film are “about” more than just this. But failing to confidently describe your own film, instead choosing the vague, almost fearful route that Hall took during the festival, suggests a preemptive worry that there was something she was likely to get wrong. This dovetailed with the film’s press cycle before and during (and likely after) the festival, where the question of why Rebecca Hall, as a white person, was fit to direct this film seemed to prevail.

The film itself is a mostly faithful adaptation. Irene and Clare (Tessa Thompson and Ruth Negga), two biracial women who pass as white in 1920s New York, reconnect after many years apart. Clare has married a white man (played by Alexander Skaarsgard) who is unaware of her racial background. The tension between her and Irene is both sensual and strained, with Irene’s bewilderment at her friend’s decision to pass butting up against her desire to reconnect. Coupled with her frustrated home life raising two boys and accommodating a headstrong husband (played by André Holland), Irene fixates on Clare, even as she tries to fend off Clare’s increasingly frequent visits. Passing features stunning black and white photography by Eduard Grau, as well as admirably stagey acting evocative of the period. Thompson and Negga make for a beguiling pair, the former’s aptitude for engaged, active listening put to especially good use. Negga is magnetic in her portrayal of Clare, at once flirtatious and unmoored, a woman who desperately hopes to reclaim her place in a community she’s chosen to abandon. Negga has a natural, arresting screen presence and a skill for embodying rather simply wearing her characters. Adaptations can be difficult to talk about, especially when it comes to measuring just how much influence the original work should have over a viewer’s judgment of the film. In that regard, I struggled with Passing. In an endeavor to flesh out an already short literary work, Hall minimizes the racial commentary of the novel. As a viewer, you notice a vacancy, an absence, whether of emotion or of motivation in the characters. In the novel, there’s far more detail, dialogue, and characterization. One would think that a film would be uniquely suited to bringing these scenes to life. But Hall seems to shy away from inventing new scenarios, instead opting to hew fairly close to the book’s plot. At the same time, she radically changes its tone, so that explicit conversations about race or class (in many cases, directly lifted from the novel) occur during scenes that seem to downplay those subjects’ significance. The urgency and momentum of the novel is instead molded into a kind of listless malaise, where time is easily lost and behavior becomes increasingly confusing.

Sian Heder’s CODA, about a hearing teenage girl named Ruby (played by Emilia Jones) who interprets for her culturally Deaf family, takes a more concerted tack in its reworking of source material. A remake of the French film La Famille Bélier, CODA preserves the original’s spirit, while improving upon its casting. La Famille Bélier received backlash for casting two hearing actors to play Ruby’s parents. In CODA, that’s rectified in the casting of veteran Deaf actress and activist Marlee Martin, Troy Kotsur, and Broadway actor Daniel Durant. Likely the standout visual aspect of the film is that it’s lit like a Lifetime movie, almost inconceivably bright, with almost no depth in its colors. But when it breaks free of Talented Working Class White Girl Destined for Greatness trappings, the film hits a poignant stride. Jones demonstrates boundless talent as a girl struggling to choose between a life of music and song and a life of hard labor on her father’s fishing boat. Her performance is sometimes hampered by standard Movie Adolescent tropes. But her chemistry with the rest of her family, and her decision not to play easy emotions (in a movie that often does) saves CODA from becoming maudlin and trite.

The rising number of high-profile films about Deaf culture, including the recent Sound of Metal, is frustrating for being so long overdue. Films like CODA showcase resilience, yes, but, beyond that, they reveal a woefully undervalued, endlessly fruitful collection of artists. The actors who play Ruby’s family are all revelations in their own way. Which begs the question as to how future films featuring and about deafness might endeavor to center the Deaf community. There’s a moment when, for the first time in the film, the perspective shifts away from a hearing one to a facsimile of a deaf one. The big climactic choir show at the end of CODA goes silent during Ruby’s duet. Heder attempts to show the audience a Deaf perspective, here communicated through an absence of sound. Its effect, though way too late in the plot, is impressive, perhaps an early glimpse at what lies ahead for more accessible filmmaking.

***

A key facet of festival-going that should be more often noted is just how quickly the media can churn out high-profile, consequential reviews. Pieces that are filed hours or even minutes after a premiere have the potential to define, or at least dominate, the early conversation around a given film. This seems unfair to the film and its production. It’s almost antithetical to good criticism, to be able to confidently judge a project so soon after first experiencing it (and to be clear, some of these critics don’t pretend to care about giving thoughtful analysis). The authority and condescension that these critics espouse in their reviews undermines what exactly criticism of any kind is supposed to do.

There’s a cliquish nature to certain groups of critics, apparent IRL when you can see them congregating in a huddle prior to a screening, but also apparent online when they parrot each other’s opinions or shoot down another person’s enjoyment of something they deemed subpar. This attitude is admittedly easy to copy because, after several days of watching dozens of films, it can sometimes feel like you’re waiting for something to truly take you by surprise, to shock or arrest you. As a result, some strong, less flashy films suffer. That felt true for selections like Nikole Beckwith’s Together Together, early reactions to which focused on how derivative or Sundance-y it was. But, more than any other year, I was reminded of how important it is to consider a multitude of audiences who would at one point be coming to that material for the first time, devoid of any foreknowledge of the actors, director, or festival vibe the film may have had.

Which is why Together Together, starring Ed Helms as a single man named Matt and Patti Harrison as a young woman named Anna who becomes Matt’s surrogate, turned out to be one of the standout premieres I saw. Funny, earnest, and directed with a light touch, the film is also a welcome celebration of the kind of platonic love that isn’t so cleanly relegated to friendship. Both loners for different reasons, Matt and Anna draw closer together without any forced sexual tension or conflict. And what conflict does occur feels believable, reflective of the hurt each person is nursing, rather than some manufactured, saccharine contrivance. Some might question the film’s tone, which never goes for the kind of obvious comedic style that other light dramas set in sunny San Francisco might. But, besides a few flaws, such as a muddled critique of Woody Allen’s films, Beckwith creates an atmosphere that puts you at ease, even when the film reaches its raw emotional peak. I wanted to rewatch it immediately after the credits rolled.

The same is true for Sean Ellis’s werewolf retelling, Eight for Silver, which might have been the most fun film this year. A gory, suspenseful film with committed performances and imaginative creature effects, Eight was unexpected given that it was featured in the Premiere slate rather than the more genre-friendly Midnight section. Boyd Holbrook (with a good British accent) leads as a pathologist in the late 1800s drawn to an English manor plagued by an unseen force. Ellis tries out a new angle on the tropes of the werewolf legend, from silver to the curse itself. That last aspect is the film’s biggest head-scratcher. Seamus, the patriarch of the manor (played by Alistair Petrie) incites the story’s action by driving out and massacring a Romani settlement that has laid claim to his land. As a consequence, Seamus and his kin are cursed by the last surviving member. The use of cultural/ethnic curses, even when they’re repurposed to emphasize the evil of colonialism as they do in Eight for Silver, still register as the remnants of a culture that relies on othering. Throughout the film, the effect of the Romani curse looms large, as does the Romani people’s absence from the rest of the proceedings. There is never any resolution to their story. Instead, we continue on with the white characters, who, apart from evocative nightmares surrounding the massacre, don’t share a passing thought for the dead. To the film’s credit, its tone doesn’t hinge on making a bold, anti-imperialist statement. Some of the comments I heard about Eight for Silver (or more accurately, read on the Sundance chat threads) complained that the film takes itself too seriously. By the time a local boy’s hand gets bitten half off by a menace only seen through the grass, in a scene that serves as a suspenseful chase and a pastiche of suspenseful chases, I was inclined to disagree.

Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr.’s feature debut, Wild Indian, also involves the biting of children, this time with a child doing the biting. A funereal, severe meditation on indigenous generational trauma, Wild Indian follows two Ojibwe boys, Makwa and Ted-O, who share a dark secret that haunts them into adulthood. Here, there is a “refreshingly” abrasive characterization and logic to these character’s behaviors. Makwa, who is regularly kicked out of his own home and physically abused by his father and his classmates, slowly begins to resent his native heritage. His anger, exacerbated by isolation and envy over the seemingly perfect lives of other kids, festers until it explodes in a sudden act of violence. He ropes his only friend, Ted-O, into helping him cover up the mistake.

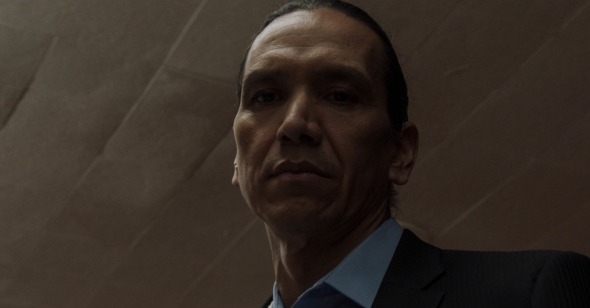

From here, the film jumps ahead in time to the present day. The roads that Makwa (played by Michael Greyeyes) and Ted-O (Chaske Spencer) have taken diverge down unexpected paths. In Wild Indian, trauma hardens rather than rots. Even as an adult, Makwa is still trapped by his anger. Greyeyes plays him with a simmering intensity, his taut frame so still that he often seems to be holding his breath. The result is a character whose compulsion towards violence as a reaction to a lack of control becomes untenable. There is a hint of Patrick Bateman’s clean, shiny exterior and deteriorating interior to Makwa, particularly when framed against the slick office environment where he works and when his extracurricular activities turn nearly homicidal. Ted-O, on the other hand, has been dealt a rough hand, with prison time and hidden guilt taking their toll. Spencer’s performance is the more inviting of the two, warm, charismatic, and heartbreaking. But the overall experience of the film around him is so tense that the atmosphere becomes one-note. Part of this might be structural, as a good portion of the narrative is set in the past with Makwa and Ted-O as children, and another large section is devoted to Ted-O following his release from prison. When adult Makwa takes over the narrative, it feels as if we are entering an entirely new story, one where, bewilderingly, the movie extends a sympathy that feels unearned.

Corbine crafts a bold arc for Makwa. He’s an Ojibwe man gone West who does everything he can to bury his heritage. “We are the descendants of cowards,” he says. “Everyone worthwhile died fighting.” But his actions are severe, played with a distinct lack of remorse, even as the film draws historical parallels to the genocide and forced migration of North America’s indigenous tribes. Corbine does seem to want viewers to empathize with Makwa, if the ending’s final scene and nudging score are any indication. He may be buckling under the weight of traumatic history, personal and cultural, but Makwa’s own shocking choices aren’t so easily explained away.