In this weekly column, one writer sends another a new piece of writing about a film they have been watching and pondering over, in the hopes that this will prompt a connection—emotional, thematic, historical, or analytical—to a different film the other has been watching or is inspired to rewatch. This ongoing column is in the spirit of many past Reverse Shot symposiums, in which writers found connections between seemingly disparate cinematic works, and it will also help us maintain personal connection among our writers and our readers.

9to5: The Story of a Movement

When the coronavirus cases in New York had just begun to peak, an acquaintance of mine had to cut her maternity leave short to resume work as an ER nurse. Soon, she was organizing nurses and other healthcare workers to hold demonstrations in front of Harlem’s Mount Sinai Hospital demanding access to PPE. In the course of days, invisible, ignored labor became “essential,” and we took to our windows at 7:00 pm to cheer them on. Then went back to our isolated lives while, between March 15 and April 15, nurses signed off on 1,281 formal protests demanding protective gear, safety measures, and better planning from their management. Most nurses, however, were too overworked to even sign petitions.

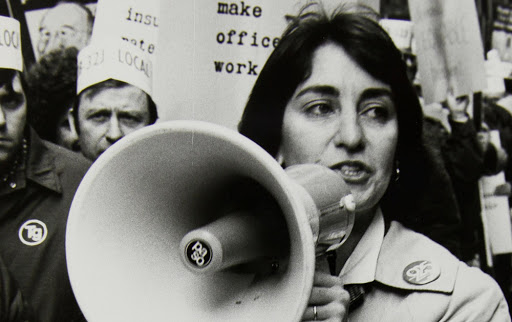

“Rai$e$ Over Roses” reads a poster in Julia Reichert and Steven Bognar’s 9to5: The Story of a Movement, a film I haven’t stopped thinking about since watching it. It tells the story of underpaid, overlooked, and exhausted secretaries (all women) in Boston who, in the 1970s, agitated, organized, and mobilized against a terrifyingly abusive work culture and demanded promotions, equal pay, childcare, insurance, time off, and other basic rights we often take for granted. Overlooked by the women's and labor movements, 9to5 institutionalized workplace feminism and unionized secretaries all across America. “My boss just fired me. What should I do?” was a question women like Karen Nussbaum, one of the group’s founders, heard all the time.

As I doomscrolled through my Twitter feed in April, it was a question that began popping up with regularity. Over a million women have functioned as essential workers through the pandemic: in groceries, fast food counters, pharmacies; often making less than minimum wage with no job security or access to childcare or insurance. Every day the clapping seemed increasingly self-congratulatory and useless.

As a story of remarkable women, Reichert and Bognar’s film does the historical work of putting faces to the shoulders we stand on. While I sat isolated, hundreds of miles away from family, and dealing with being unemployed and—more scarily—uninsured, it was easy to feel alone and hopeless. Though I have never been a secretary, watching 9to5 has shown me a legacy that I didn’t know I could lay claim to.

I have survived the last few months on the kindness of friends and have often despaired wondering what it would be like if they stopped being kind. Never before have I found myself at the intersections of a crisis this multi-pronged, and every time I have thought about what can make it better, the answer has been “talking to more people who are going through this.” 9to5’s biggest reassurance for me was its reminder that nothing gets done if you don’t get on the streets and shout your demands, and that the solutions to problems are always and will always be political. Broken storefronts seem like rash acts of vandalism only to people who have happily ignored the decades of violence that has angered people. 9to5 taught me the correct word for “talking to more people who are going through this”: organizing.

For years, Reichert and Bognar have been making art that documents the political struggles of the American working class. [Ed. note: Julia Reichert is the aunt of Reverse Shot’s co-editor, Jeff Reichert.] In 1971, Reichert founded New Day Films, a distribution company that would support the contemporary movement for women’s rights. Her films, made in partnership with, first, Jim Klein—including Union Maids (1977) and Seeing Red: Stories of American Communists (1983)—and then with Bognar—The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant (2009) and American Factory (2019)—have been exercises in making activist art that reminds and educates us of political pasts. They strive to organize their audiences into resistance. We see many women speaking in 9to5, but there is no single hero in the film—not even the fantastic Jane Fonda, who extended her allyship by helping to conceive and star in the eponymous 1980 comedy inspired by the movement.

Mirroring the movement, the film passes the baton of the narrative from one woman to another—from city to city, state to state, telling a story that covers the breadth of the country. Reichert and Bognar, through 9to5 and their other films, stress the immense power of individuals uniting in resistance. It’s a reminder that we crave the communities we’ve built, especially in a time of isolation that makes us feel like we’re drifting further and further away from each other. The film and the movement remind us, as Dolly Parton sings, that we all have dreams that’ll never be taken away. —Bedatri D. Choudhury

Fast Food Nation

I was happy to see that you picked a Reichert/Bognar film, Bedatri, as the amorphous fog that has been my pandemic movie-watching marathoning has included both American Factory and Growing Up Female (1971). At least I think I watched the former post-outbreak—my deadening omnivorous intake, with everything seen on the same modest Vizio TV, has flattened the last year or so of home views into the same indistinguishable mush. I look forward to seeing this new documentary also because I finally watched the (objectively delightful) Fonda-Parton-Tomlin version for the first time in August, a shameful omission righted.

I was moved by the descriptions both of your ER nurse acquaintance’s organizing efforts and your own precarious situation, and agree with you (as no doubt do your selected filmmakers) that leaning on friends, talking to the like-minded and ultimately collectively organizing provide the best weapon against both world-historic crises like this and just everyday employer exploitation. I fret, though, that six-plus months of widespread telecommuting in the industries in which it’s feasible has given management everywhere invaluable data showing that workers in those industries needn’t ever be in the same place, making it easier for leadership to prevent unionizing, downsize, surveil, and make workers afraid to ask for improvements lest they’re axed for being ungrateful. I am fortunate that I have been able to hang on to my own inessential nine-to-five through the pandemic, a “lucky to have a job” grace management has been keen to remind us of at all-hands meetings.

While I can’t deny enjoying some of the perks of telecommuting, the worker atomization it ensures will require redoubled and re-engineered efforts to combat exploitation. Meanwhile, even the possibility of organizing in many industries was long ago methodically squeezed out via tactics like encouraged turnover and dirt-poor pay. That includes the fast-food industry, and when you mentioned the unclapped-for fast-food counter essential workers, I thought of Richard Linklater’s Fast Food Nation (2006), a favorite I saw on release and happened to rewatch in July since my partner hadn’t seen it. I was mostly excited to revisit a handful of performances I remembered loving (Greg Kinnear, Patricia Arquette, Catalina Sandino Moreno, Esai Morales), but then I quickly realized I had inadvertently happened on a film “more relevant now than ever”—a wince-inducing expression that nonetheless cannot be denied considering the film’s treatment of illegal immigrant exploitation and the planet-eroding effects of unchecked (food) capital.

Now, as then, Linklater’s film struck me as a most brilliant Trojan horse, delivering the sobering, appetite-destroying truths of Eric Schlosser’s nonfiction source in the form of a still-trendy “network narrative” feature (this was the year of Babel) full of famous faces and shot and scored with professional gloss. Fans of Ethan Hawke, or the then-hot Wilmer Valderrama, might come to see them, and leave having sat through an extended kill floor sequence and having learned the amount of fecal matter in burgers deemed acceptable by executives. Without ever seeming like it’s grasping to force connections, or tsk-tsking the mass millions who choose to eat fast food, the film weaves together several strands (immigrants who end up working in a food processing factory, a cashier-cum-student becoming slowly radicalized, an exec’s journey of conscience) in a manner ideally suited to a global mega-business like fast food, to entertainingly illustrate the blood, sweat, lies and literal shit that go into every quick meal.

After the last few years of relentless, climate-poisoning industry deregulation, it’s fair to say that the kind of lamentable conditions depicted in Fast Food Nation have only gotten direr. The hardest scene to watch is a gory factory floor employee-mangling, and my own recent doomscrolling brought me the news that the U.S. Department of Agriculture is allowing facilities to actually speed up their lines, further endangering workers who have been there throughout the pandemic. So in a film leavened with cozy, warm moments (Arquette and Hawke’s adorable brother-sister act), Linklater is to be commended for the film’s pessimism, which ranges from comic (“liberated” cows mooing in confusion) to heartbreaking (the sexual degradation that leads to that tear-inducing final abattoir tour inspired by Fassbinder’s In a Year of 13 Moons) to ironic (a new van full of immigrants being treated to a “Mickey’s” meal the second they enter the country). Kinnear is phenomenal throughout as the conflicted marketing exec who cottons to the industry’s dark side and seems to want to blow a whistle, but in the last moments is right back hawking “Calypso Chicken Tenders.” The fight is too big for the un-unionized to go it alone. —Justin Stewart

Reverse Shot is a publication of Museum of the Moving Image. Join us at the Museum for our weekly virtual Reverse Shot Happy Hour, every Friday at 5:00 p.m.