Brokedown Palace

by Beatrice Loayza

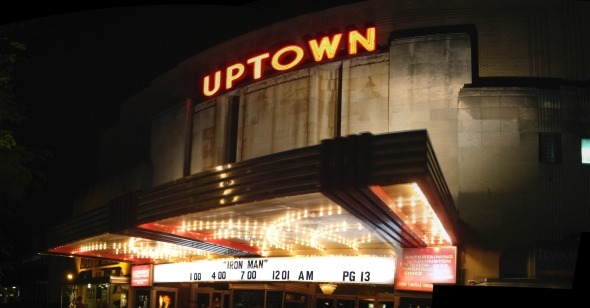

I’ve been thinking about those sticky summer days when I first moved to the city: my forehead slick, ankles puffy with bug bites, the slightly sour scent of hairspray and cigarette smoke trailing me like a cape. And then there was the movie theater down the road, like a beacon casting a gentle glow. “Uptown Theater,” it read in candy-red neon lights. I’d sit in the front row of the balcony, my bare feet stretched out on the railing, thick thighs spilled out onto frayed cushions, sweat dried into a salty lacquer. I can’t say that it was a particularly fancy joint. My body felt crunched and abused after sitting in those spartan seats for two hours. The carpeting had this awful stained-yellow hue. But it was my big, beautiful movie palace—all the more special because I could stumble home and flop into bed less than ten minutes after the credits rolled.

Back then I was living in a dingy group house in Cleveland Park, a neighborhood in northwest D.C. known for its stately single family homes. Go half a mile north and you’ll find Sidwell Friends School, Malia Obama’s alma mater. Wander east and you’ll stumble upon the William Slayton house, one of only three residential homes designed by the Japanese architect, I.M. Pei. Our house was an ugly, run-down anomaly: “the neighborhood crack house,” my roommate quipped; “a beach house in the city,” said another. Rent was cheap because the landlord, a hippie-ish older woman, had no interest in renovation or upkeep. It had its charms—a retro mint-green paint job, a large front porch, rose bushes in the back—but we all knew it was falling apart. Our place remained in the ’70s while around it homes had been torn down, rebuilt, and redesigned into custom-tailored mini-mansions. I was the only female roommate, and the youngest by a long shot, but we were all people of color, all working day jobs, all playing gigs, scribbling, sampling, and performing by night. Before the “beach house,” none of us had ever lived in such a pretty neighborhood. That we had ended up there, that this house even existed, that someone hadn’t already bought it out and made a fortune from it, felt unbelievable. In the spring, cherry blossom petals consumed the sidewalks so you were always stepping on a sheet of pink. There were kids everywhere, little kids with little backpacks and still-wobbly gaits.

There isn’t much in the area in terms of nightlife. The feel is more wholesome and clean-cut, doubly so because a spatter of art deco–style buildings line the central commercial hub on Connecticut Avenue, summoning visions of 1950s Americana, poodle skirts, and ice cream sodas. With its limestone panels and glittering marquee, Uptown Theater stands at the center of it all, beckoning residents young and old into the embrace of its single, curving, 70-foot screen. Because it only has one screen, the same movie might be played over and over for weeks at a time. On Fridays and Saturdays you might see folks queuing up outdoors; and depending on the movie those lines could bend around the block. It looked like how neighborhoods were supposed to look in the movies—warm, friendly, timeless. Despite its cherished standing in the community, the Uptown proved to be a vintage novelty, tenuously preserved but nearing death.

***

The Uptown first opened its doors in 1936. Cain and Mabel, a song-and-dance comedy starring Clark Gable and Marion Davies, was the first film to play at what was originally a Warner Brothers-owned theater. It would undergo several transformations throughout the years to sustain the latest Hollywood innovations. In 1956, the venue introduced a new 70mm Todd-AO format, early high-definition single-camera widescreen. A few years later, the projection booth was restored to install the dramatically wider, three-projector Cinerama format, which upgraded the venue from a mere neighborhood haunt into something singular and glamorous and worthy of the uptown trek. Several world premieres of legendary films took place in its hallowed halls: 2001: A Space Odyssey, Dances with Wolves, Jurassic Park. In the wake of James Cameron’s Avatar, commercial theaters across the nation made the transition to digital, and the Uptown was no exception—it retired Cinerama in 2010. That year, Tron: Legacy was the first movie shown digitally at the historic venue.

In the past decade Uptown’s programming has been whittled down to the monolithic blockbusters du jour, the Star Wars, Avengers, and Pixar movies certain to attract wider audiences and impassioned fandoms. A coworker who attended Georgetown several decades ago recalls camping out in line at the Uptown with a squadron of fraternity brothers hours before the first screening of The Empire Strikes Back. On the Friday night opening of The Force Awakens, I hitched a ride home in one of the multiple cars that same coworker had called to transport his crew to the Uptown from our office, a more convenient gathering point. We arrived in Cleveland Park to a block party of lightsabers and Wookiee costumes and jittery, squirrelly children. I bid them adieu, eager to escape the madness and mildly repulsed by the chronic popularity of the franchise, which seems to lodge like plastic in the bloodstreams of its loyal followers.

I avoided the Uptown’s weekend crowds and opted for the weeknight slumps that saw the 800-plus capacity theater flecked with ten or twenty people all scattered about, hunched and shifty-eyed as if each of us had something to conceal from one another. The enormous size of the space magnified its emptiness on these days; our warm bodies were so small and remote before the engulfing screen. There are other, more cinephile-approved theaters in the area that boast invigorating, unorthodox programs. I can take the train downtown to the Landmark on E Street for new art-house and foreign fare, or make my way north into Silver Spring on the border of Maryland and D.C. for the repertory offerings of the AFI Silver. But heading to these establishments requires greater intent, drawing upon a different type of desire than whatever compelled me to wander into the Uptown to be devoured by a big, stupid blockbuster. Since moving out of Cleveland Park, “hit” movies have largely been eradicated from my theater-going diet—a rather cleansing effect. Yet I find myself missing that view from the balcony, the feeling of peering down at those churning, sexless spectacles, and the slightly melancholic indifference of it all.

I’m reminded of Bette Gordon’s Variety (1983)—a fundamentally lonely movie that I, contrary to custom, had the pleasure of watching among friends in a bitsy, warm theater filled to capacity at this January’s International Film Festival Rotterdam. Sandy McLeod plays Christine, a “good girl” who gets a job selling tickets at a porno theater in Times Square back when Times Square was full of peepholes, black curtains, and projection rooms that played endless reels of hardcore and kung fu, day and night. Fascinated by this new world of erotica, fashioned for the gazes of men, Christine ultimately latches onto one of her regulars, a wealthy mystery man, with whom she grows desperately, almost pornographically obsessed. Occasionally, Christine wanders into the screening room while on the job for a lurid eyeful—that’s when we get a view of the theater and the men inside, like golems, stunted and entranced. Among them might be De Niro’s Travis Bickle, from Taxi Driver, slouched in the fourth row, feet propped up like an antsy kid. Cinematic visions of the porno theater are vested with a particularly male sense of freedom. Variety disturbs this notion by injecting a curious female presence, highlighting the indifference and capriciousness of such freedom, and the dangerously coded spaces that accommodate it. I like the idea of trotting into the movies whenever you please, and the sorts of movies that ask nothing of you, not even that you show up on time—come whenever, they shrug. That seems to me like an ideal way of approaching the notorious three-day Marvel marathon, which, like the 24/7 porno theaters, must carry a distinct scent.

The Uptown always played big, splashy movies because that’s what sold, and management couldn’t and wouldn’t risk showing something that wouldn’t sell. When there’s no room for cinema beyond mechanical, sure-fire attractions the movies grow numbing. It’s a numbness that comes as a relief, so we pursue it. But it smells of death. I recently watched Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show in bed, the blinds shut tight to keep out the day and its demands. In that movie, time moves forward like skipping rocks. Its plaintive vision of small-town life in 1950s Texas depicts a pockmarked nostalgia, the coming of age as the disappointingly premature climax, the long hangover, the chalky Tums after the tequila and the Mexican food. As the title suggests, the closure of the town cinema, a beloved gathering spot for handsy teens and neighborhood layabouts, achingly signals the death of something much greater than itself—a youthful American idealism that dreams big, undaunted.

It’s easy to imagine the Uptown’s former glory, because shades of that glory are reproduced in its imposing facade, the striking glow of the marquee. But those spasms of cinematic excitement occasioned by Star Wars were deceptive, all the more so because they took place right in my backyard, among the seemingly impenetrable idyll of so many wealthy, white families. The Uptown shut down indefinitely in early March for reasons unrelated to the pandemic; ticket sales had long declined, and AMC’s lease was about to expire. Like the “beach house,” my ramshackle dwelling down the block, it was an artifact, an abnormality in a place that had long moved on and supposedly improved.

Since learning of the Uptown’s closure, I’ve perused testimonials offered by older D.C. residents with much longer, more robust personal relationships to the theater. Someone remembers watching How the West Was Won from the balcony, holding hands with Jane Doe on opening night of The Thin Red Line, gawking at Raiders of the Lost Ark cradled between mom and dad. Such a distinctly American nostalgia for the neighborhood theater never really existed for me—or my parents, or my grandparents, in the first place. Yet I felt it—whatever it was—in those years living near the Uptown, even if at that point it only conveyed a small fraction of its former allure. Its hold on life was slight, at times frustrating and laughable. But, oh, the sting of its death.

Reverse Shot is a publication of Museum of the Moving Image. Join us at the Museum for our weekly virtual Reverse Shot Happy Hour, every Friday at 5:00 p.m.