Show and Tell

Daniel Witkin on Sergei Loznitsa’s Donbass and The Trial

In one of the disquieting, seemingly disconnected vignettes that make up Donbass, Sergei Loznitsa’s absurdist roundelay through occupied Ukraine, a German journalist chats up a small battalion of armed soldiers. He asks them where they’re from, but this turns out to be a question more fraught than one might initially expect. They hem and haw before hitting upon the name of a nearby village. “They say they are from Gorlovka,” the journalist’s translator hopefully clarifies, “but they are making tricks with us.” It would certainly seem so; the men chuckle amongst themselves like adolescents who are less concerned with obscuring their mischief than conveying that they are, in fact, in on some joke.

The soldiers, of course, are not from the Eastern Ukrainian town of Gorlovka (Horlivka in Ukrainian) but from Russia, whose military presence in the country was denied by Putin until 2015, after they had been active for over a year. As with his disavowals of the masked “little green men” and “polite people” who manifested in Crimea before the Russian annexation, the president’s denials were delivered with something of the smirking air of the pseudo-Gorlovkans. Both instances can be counted as examples of a particular sort of falsehood that at least feels a good deal more prevalent of late, one less intended to actually deceive anyone than to flaunt the extent of what one can get away with. It’s something to which many of us have had to accustom ourselves. To be scandalized by official dishonesty feels quaint, almost prudish, and on the other side, the embarrassment of being caught in a lie somehow negligible in relation to its presumed utility or mysterious necessity.

To process the layers of brutality and often half-hearted deceit that constitute much of contemporary public life in the former Soviet Union is no enviable task, but Loznitsa has taken it up with gusto. He is extraordinarily prolific, maintaining parallel careers as both a fiction filmmaker and a documentarian, either of which would alone suffice to earn him a place of note in European cinema. In the past year, he has premiered both a fiction feature, Donbass, and a nonfiction one, The Trial, a found-footage account of an early Stalinist show trial. While Loznitsa the fiction filmmaker and Loznitsa the documentarian share the same concerns, they can curiously come off as temperamentally distinct. The former tends to be virtuosic and confrontational, while the latter is for the most part methodical and sardonically detached, even if both maintain a telling severity.

The fault lines along which Donbass specifically unfolds—between Russia and its neighbors and, more broadly, the contested borders of East and West—are those that Loznitsa’s work has straddled throughout his career. Though his films are always implicitly or explicitly about Russia, they are not of Russia. An ethnic Belorussian raised in Ukraine and based in Germany since 2001, Loznitsa is a quintessential product of the USSR, the last of the great multiethnic European empires, though his feelings toward the erstwhile Soviet imperium are fraught to say the least. And indeed, Putin’s actions in Ukraine would make it seem impossible to be too suspicious of Russia, too jaundiced about its motives. Essentially spreading chaos for chaos’s sake, Putin’s nakedly cynical intervention in Ukraine has not only gone unpunished, but seemingly redounded to the benefit of Russia’s long-term strategic goals. None of this has been lost on Loznitsa. In his fiery depictions of the symbiotic relationship between human stupidity and evil, there is a case to be made for him as one of the angriest filmmakers working today.

Donbass is the film in which Loznitsa’s work as both fiction and documentary filmmaker come into closest harmony. Comprised of largely disconnected, almost sketch-like fragments (the director has cited Buñuel’s Phantom of Liberty as an influence), the film has a pronounced ripped-from-the-headlines quality, even as it casts doubt on the veracity of the headlines themselves. The film’s first scene shows a group of actors preparing for what seems to be a standard film production, sitting around and shooting the shit before we learn their actual roles acting as artificial witnesses for television coverage of the conflict. The immediately disorienting reveal comes as they hurry through what appears to be a war zone, accompanied by a television crew attired like riot police. The scene cuts out before one can properly ascertain not only what’s going on around them but also how fake it truly is. Where does the set end and reality begin?

This is all authentic to the war in Ukraine, in which truth and narrative have been battlegrounds no less fundamental than those upon which real people have fought and died. I lived in Moscow throughout 2014, the year that the Ukraine conflict metastasized, and while this gives me no greater insight into the actuality of what was going on in the Donbass, I did have some experience of how it was packaged and received within Russia itself. The Arab Spring and the 2012 protests in Moscow sensitized Putin to such photogenic expressions of popular revolt, which he regarded as orchestrated by the State Department and other Western interests (in a dark irony, this attitude toward protesters has now been adopted more or less wholesale by the American right, which has also taken up the common boogeyman of George Soros). When one such outburst erupted in Ukraine, traditionally regarded by Russians as a sort of little brother state—and on the eve of the Sochi Olympics, no less—he acted reactively but decisively. The seizure of Crimea was bombastic and triumphalist, but the escapade into Eastern Ukraine was darker and more surreal; the violence was covered on TV with moralistic relish as a warning to Russians of what might well happen should they ever decide to throw off their similarly corrupt leadership. Of course, a good deal of this was fake, and transparently so. Maybe citizens elsewhere believed Putin’s claims that there weren’t Russian soldiers in Crimea, but in Moscow they sure didn’t appear to. Likewise, the fake TV eyewitnesses who kick off Donbass come from the real example of certain eyewitnesses who were recognized after appearing on the news with suspicious frequency. But counterintuitively, none of this detracted from the effectiveness of the spectacle. Television has been a major part of warfare since Vietnam, but at times the war in Ukraine seemed to exist expressly so that it could be filmed on television.

Unlike in Loznitsa’s previous fiction works, the camera throughout Donbass maintains the probing, inquisitive quality one might expect from a documentary (if not necessarily one of his documentaries). The movie elapses in what feels very much like real time. Scenes tend to begin significantly in advance of their primary action, and frequently invoke the experience of waiting, something the film posits as constitutive of wartime. In addition to reportage of the primary camera, others litter the landscape as well, from the devices of the proliferating TV crews to the smartphones on which everyday citizens capture the chaos. At times, these will overlap. At one point, we’re given a contrived tour of an underground bunker, which is interrupted when an upper class woman, presumably the partner of some or another oligarch, comes by to retrieve her recalcitrant mother. The latter’s refusal throws the woman into an impotent rage, and as she batters the door, behind which the mother has locked herself, a crowd gathers, causing the woman to reorient her tirade toward some hapless bumpkin who has decided to document her outburst. It’s this focus not only on the process of documentation, but also on how reality reconfigures itself around it that gives the film its distinct character. Donbass emerges as a rare specimen, the war film as backstage musical.

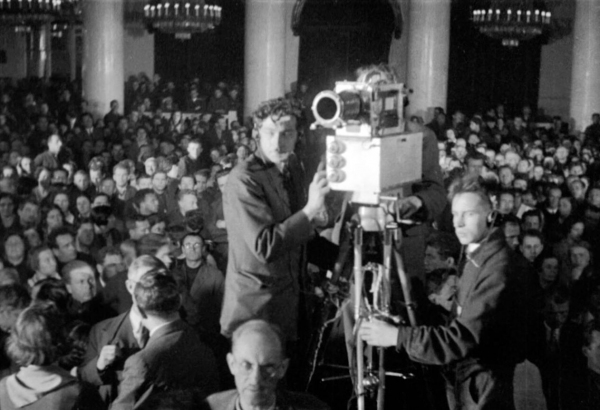

If Donbass might give the impression that the ouroboros-like relationship between media and politics is somehow a uniquely postmodern phenomenon, The Trial serves as a bracing corrective. Consisting of newly restored found footage, the film shows the step-by-step machinations of an early Stalinist show trial, in which a group of high-ranking party members stand accused of working with Western powers to commit industrial sabotage in order to precipitate a foreign intervention. Named, of course, for the novel by Kafka, who has been Loznitsa’s key literary touchstone for some time now (despite its Dostoevskian title, his previous feature A Gentle Creature was in many ways an extended riff on The Castle), the Russian title shares the double signification of the German, meaning both “trial” and “process.” And indeed, a process is what we are here to observe, a set of designated actions that must, for one reason or another, be carried out. The victim’s complicity, however, implies that some of the messier business (torture, familial threats, and the like) has already been seen to, so for all the film’s unimpeachable thoroughness, what we will be witnessing is limited to said process’s conclusion.

Aside from a couple of Kafkaesque details (at one point a literal “Mr. K.” happens into Moscow), the content of the trial itself is remarkably boring. Rigorously micromanaged from the top down, the witnesses are confined ruthlessly to the script, and do most of the work of condemning themselves. The result is surprisingly devoid of conflict, with accusers and accused alike speaking in the same voice, using the bureaucratic syntax of Marxism-Leninism (“the methods of sabotage were revised” and so forth) to expound on a conspiracy that contains not the slightest element of plausibility. In this, The Trial resembles Loznitsa’s previous found-footage doc, The Event (2015), in which a pro-democracy demonstration in 1991 Leningrad is shown to be just as orchestrated and perfunctory as the Soviet-era pageantry it’s ostensibly displacing. With the trial’s main action turning out to be so comprehensively frictionless and Loznitsa disinterested in putting forth any sort of theory as to why all of this is happening, one’s attention is directed instead to the behavior and human ticks of the individuals caught up in the spectacle. “I thought I shouldn’t reveal any names now,” says a genuinely confused victim after the judge evidently contradicts his preshow direction. As the sentences are being read out, another of the condemned absentmindedly gives off a dreamy smile of either enervation or relief.

The Trial, then, becomes a portrait of the manifestations individual fear that taken in sum amount to mass terror. Oddly, this fear does not emanate chiefly from the defendants themselves, who have most likely already been through the worst and are seemingly looking forward to putting this whole process behind them. Rather, it is the spectators and judges who, still having something to lose, look the most nervous, as well they should. If there’s a certain interchangeability between the accusers and the accused—both are, after all, loyal Bolsheviks of some standing—this is not lost on the judges themselves, many of whom, as we will learn in the film’s epilogue, are to meet the same fate. The onlookers also had better not be too sloppy in playing their part. One of the film’s most jarring cuts comes early on as we see a mob assembled to demand justice for the traitors. Accompanied by the sounds of vociferous jeering, this long shot gives way to a closer image of citizens shuffling around listlessly, eyeing the camera itself with mortal suspicion. The lifeless choreography makes for the starkest contrast with the darkly anarchic Donbass. While cameras and their operators occupy a privileged position in Putin’s info-war, here we can imagine the figure behind the camera being as frightened as all the rest, anxiously determined not to fuck up or else.

One of the genuine surprises of The Trial is the reveal that many of the sentences were never fully carried out—indeed the survival rate of the judges and prosecutors was no better than that of the condemned. Many figures in Donbass, however, aren’t quite as lucky. Brutal and shocking acts of violence tend to arrive in Loznitsa’s fiction films with a sort of death-and-taxes inevitability, and sure enough it’s only so long until the sounds of gunshots pierce the winter air. More effective is an earlier scene in which a captured Ukrainian operative is paraded through a separatist city and set upon by a growing mob; this extended, gradually escalating set piece lays bare the psychic costs of all of the imagery we’ve seen produced throughout the film. And sure enough, smartphone footage of the man’s degradation pops up in a later sequence, adding another element of ribaldry to one of the more aggravating wedding scenes one is likely to encounter anywhere, showing the vicious circle spinning ever onward. Donbass and The Trial may never arrive at a place of historical truth, but that isn’t necessarily the point. Instead, they take up our great plague of fraudulence, and they do so with justified ferocity.

Donbass played Friday, January 11, 2019, and The Trial played Saturday, January 12, 2019 as part of Museum of the Moving Image’s First Look 2019.