To Tell the Truth

Kent Jones on Let There Be Light

The gaps between rhetoric, intention, and reality open wide in John Huston’s Let There Be Light. Fifty years after the fact, you might ask: what is it? A documentary? A propaganda film? A semi-dramatic film with “real” actors, disguised as a documentary, an unwitting forerunner of the most interesting side of early 21st century cinema? This terrifying, bewildering, eloquent, synthetic film resists easy judgments. I would call it a piece of failed propaganda, a movie made for a specific reason with a specific goal in mind. What exactly gets in the way of attaining said goal? Namely, everything that made Huston an artist: his instincts, his extraordinary sensitivity, his way of honing in on the issue at hand like a water witch with a divining rod. In the end, this is a movie best understood as an artifact of that brief postwar moment when Hollywood wrestled with the truth, when the urge to cosmeticize was, for an ever-so-brief moment, automatically questioned and even resisted. Just as in fiction films of the period like From This Day Forward, Till the End of Time, and, of course, The Best Years of Our Lives, there is a conflict between duty to country and duty to reality, and between the re-touched and the unvarnished.

When Richard Schickel was making his TV documentary Shooting War, he made a fascinating discovery. Many of the most famous wartime documentaries were faked, from Ford’s Battle of Midway to Huston’s Battle of San Pietro. Directors who had internalized the imperative of the “presentable” image, operating on directives from the war department to discard overly shocking footage, used model planes for special effects shots and staged many of their most “authentic” scenes.

With such knowledge in hand, one could raise similar questions about Let There Be Light. At certain moments, the camera placement seems a little too exacting for an intimate, on-the-spot documentary about disturbed soldiers; and, as many people have pointed out, the speed of recovery for some of the patients is so fast that it strains credibility—can all these breakthroughs really be occurring on camera? There is a hypnotism sequence that seems way too perfect—doctor quickly hypnotizes amnesiac patient, patient immediately remembers his name and the suppressed memory of battle that’s plagued him in the first place. The lighting is just right: dramatic but not overly so, the perfect look by chance rather than skill or art. And, as opposed to other scenes in the film, where the positioning of two 16mm cameras seems valid and possible, the space here seems too tight for the scene to have been done without repositionings.

Huston was given quite an odd set of tasks by the war department. He shot the film at Mason General Hospital in Brentwood, Long Island, under the working title “The Returning Psychoneurotics” (more suitable for a movie about New York critics returning from Cannes). Huston was ordered to include the information that very few soldiers fell into the “psychoneurotic” category, to lessen the stigma attached to this “disorder,” and to point out that the qualities that make for a successful soldier may not necessarily be the qualities that make for a successful civilian, and vice-versa. Perhaps the war department, or perhaps Huston, saw fit to draw a portrait of the hospital based on the assembly line model, in which soldiers go in as hopeless wrecks and come out as happy, healthy citizens, ready to return to normal life. The film moves in this direction at a fairly sprightly pace, and Huston’s rhetorical ace in the hole, apart from wall-to-wall music, is the narration ebulliently delivered by his father, one of the most comforting and well-known voices in American movies.

On a purely rhetorical basis, it’s easy to dismiss Huston’s film. But Huston was an artist, and it’s safe to say that while he may have thought he was performing all his assigned duties with flying colors, he ultimately wound up undermining his own film. Which is why the war department confiscated the print right before it was about to be screened at the Museum of Modern Art in 1946, and subsequently locked it up for the next 35 years. The official reason was that the department wanted to protect the identity of the soldiers, and when Huston went to look for the signed releases he had obtained from every participant, they had disappeared. Huston’s theory is that the film put a dent in the “warrior myth,” and in the broadest sense he’s probably right. But having recently taken another look, I would venture a guess that there must have been a few discerning viewers in the war department who saw right away that many of the images caught a deeper level of suffering than the rhetorical armature of the movie could possibly bear. There’s a similar dilemma on display in Till the End of Time and The Best Years of Our Lives, in which an intended message of comfort and reassurance is undermined or weakened by the details. From a purely rhetorical standpoint, they’re all uplifting, and it’s purely on that basis that they’ve been criticized. From a more closely considered, filmic viewpoint, they are portraits of anxiety, doubt, disenchantment.

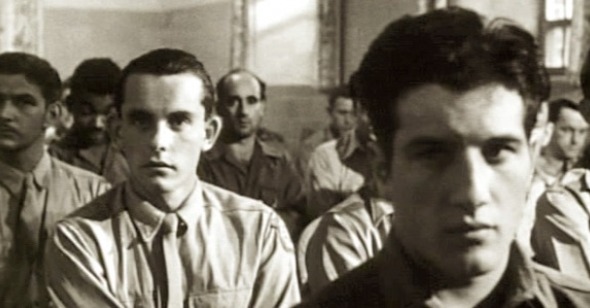

There are key moments in Huston’s film that tell the beginnings of the story Terence Malick would finally finish, so many years later, with The Thin Red Line. Movies that show “the horror of war” have a much easier task than those that attempt to show its after-effects: they take place in high-pressure, instantly dramatic arenas, in which terror finds an objective correlative in the violence of warfare. Much more difficult to show is the internal damage, the psychic shattering, splintering, as it affects day-to-day existence. As Huston’s moving camera-eye surveys the faces of soldiers during the intake scene and records their words, the dark, quiet sobriety is overwhelming. Many of the soldiers discuss their childhoods, their loved ones, their parents. War has uprooted their sense of themselves, their actual identities. Perhaps the single most heartbreaking moment in the entire film finds a black soldier breaking down under the weight of self-doubt, lamenting the loss of his self-confidence, recalling the fact that he and his fiancée could “surmount any difficulty.” (There’s no racial editorializing in Huston’s film, but one has to wonder if the mixture of black and white soldiers, far from the reality of segregated combat units, was enhanced especially for this film. When we see the same soldier later in the film, after he’s been cured, sharing a romantic moment with his fiancée, one also has to wonder whether this was yet another reason for the army’s rejection of the film.) As Let There Be Light continues on its optimistic way and the soldiers begin to “recover,” you start to wonder how long it will be before they begin to withdraw from the outside world that is allegedly welcoming them with open arms.

This movie, made in peacetime, is at war with itself, much like Till the End of Time and Best Years. The conflict between frankness and optimism was never felt more keenly in American cinema than in the movies made during this historical moment. So many years later, an attentive viewer won’t come away from The Best Years of Our Lives remembering the uplift, but the despair and doubt—the moment where Dana Andrews finally gets a job is overshadowed and overpowered by his nightmares and his final ramble through the field of abandoned planes; you don’t leave Till the End of Time thinking about the buddy-buddy camaraderie between Robert Mitchum and Guy Madison, but the harrowing scene where Madison and Dorothy McGuire sit on either side of a vet with a bad case of the shakes at a lunch counter; and you don’t remember the final, preordained bus ride to a bright future in Let There Be Light, but those faces, emptied of certainty and comfort, knowing that their destiny is to face a future eternally haunted by a past they never asked for.