Garbage Collection

Vicente Rodriguez-Ortega on Jorge Furtado’s Isle of Flowers

Today, Brazilian cinema is known for its history of variety—Glauber Rocha’s epic and highly aestheticized tales of the cangaçeiro (the peasantry in Northeastern Brazil) such as Black God, White Devil (1964) or Antonio das Mortes (1969); Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s reimagining of Italian neorealism in films such as Barren Lives (1963); the gems of the Tropicália movement, including Joaquim Pedro de Andrade’s Macunaíma (1969); and, of course, more contemporary efforts that, with varied aesthetic conventions, touch upon a series of topics dealing with social inequality and racial discrimination: Héctor Babenco’s Pixote (1980), Walter Salles’s Central Station (1998), and Fernando Meirelles and Katia Lund’s City of God (2003). Yet largely forgotten by international viewers is the so-called “Cinema do Lixo” (“cinema of garbage”) movement, which Rocha helped found and which lasted through the end of the sixties. But strategies of this subgenre can still be seen today.

Tired of the Tropicalist Orientalism of commercial cinema, Rocha wrote the famous manifesto “An Esthetic of Hunger,” pushing Brazilian and Latin American filmmakers toward different methods. Back in the Sixties, film critics and practitioners aimed at creating a type of cinema that would deal with real people and real situations. In the words of Cuban critic and filmmaker Garcia Espinosa, an imperfect cinema—that is, a cinema that “must above all show the process which generates the problems. It is thus the opposite of a cinema principally dedicated to celebrating results, the opposite of a self-sufficient and contemplative cinema, the opposite of a cinema which ‘beautifully illustrates’ ideas or concepts which we already possess.” This evolved in different ways throughout South America, in Brazil resulting in the “Cinema do Lixo.” These films, on the one hand, adopt a “garbage aesthetic,” as a tool for separation from the high production values of Brazilian and foreign mainstream cinema, and, on the other, deal literally with garbage as a signifier of poverty and social exploitation in Brazilian society. Perhaps the most remarkable work springing from this loose trend is Rogério Sganzerla’s The Red Light Bandit (1968), a Godardian tour de force characterized by a fragmented narrative method that leads up the infamous bandit encountering his own demise in a garbage dumpster.

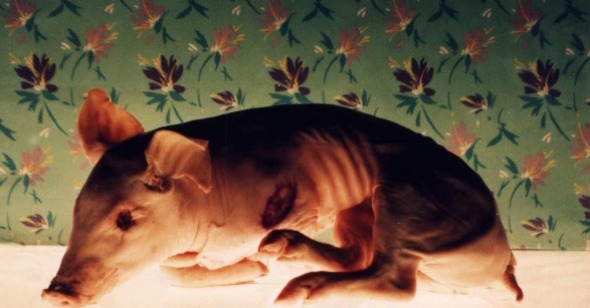

The 1989 short Isle of Flowers, a social critique about poverty in contemporary Brazil, is a direct descendant of the Cinema do Lixo movement, directed by renowned director Jorge Furtado, who remains a popular filmmaker to this day, touching upon social issues in documentary, fiction feature, and TV work. This nonfiction work of collage opens with an unequivocal declaration in onscreen text: “This is not a fictional film. There is a place called the Isle of Flowers. God doesn’t exist.” Isle of Flowers is entirely under the power of a commanding, uninflected voiceover that takes the spectator from a Japanese tomato plantation owner to a perfume seller to, ultimately, the titular island, where flowers are long gone, replaced by mounds of garbage—it is, basically, a human receptacle surrounded by water on all sides. Throughout, the narrator offers a series of free associative digressions that take us through nothing less than the history of modern capitalist humanity in thirteen brief minutes. This all leads up to the existence of the Island of Flowers, a clear enough metaphor for the core of all social inequality. By the time we reach the end, and we witness how impoverished children and elderly women pick from a dump the food that has been refused by pigs, we realize that the film’s opening words are not meant as a mere attack on religious thought or faith. It distills the logic of exchange in contemporary, capital-driven societies to reveal the nearly perverse economic inequality and social discrimination that forms its backbone.

Regularly acclaimed as the best Brazilian short of all time and one of the greatest feats of the short-film format, Isle of Flowers takes no prisoners. It’s a caustic, unconventional state-of-the-world cine-essay that offers a “tomato” as its protagonist and utilizes what we may label as an aesthetic of verbal contamination to structure its narrative—that is, the narrator makes a statement, and then he takes a word or a phrase from the previous sentence and places it into the next and so on. Then, juxtaposing the narrator’s words with ironically layered images, Furtado brings together apparently unrelated motifs such as the nuclear bomb, the Jewish holocaust, the creation of money and profit, the creation and selling of perfumes, the harvesting of tomatoes, and, of course, garbage. Mostly using a highly ironic and satirical tone, the narrator takes us from Egyptian pyramids to the contemporary Brazil seamlessly through an aesthetic of heterogeneous images that range from animated cut-ups to stock footage to unaestheticized live-action material. Yet the narrative is not totally fragmented; the tangential lines of discourse do in fact reconnect. In the same way a specific statement contaminates the next, the juxtaposed images not only gather more stimuli for the spectator to confirm the narrator’s political and social views but also deviate from the digressive linearity of the voice-over to offer their own complementary insights on contemporary societies.

“What places human beings behind pigs in the priority of choosing food is that they do not have money or an owner. Being free is the state of one that has freedom, freedom is a word the human dream feeds off but no one can explain or failed to understand.” As the narrator makes his closing statement, Furtado leaves us with a succession of slow-motion images of children and old women picking through what remains of the food the pigs’ owners deemed unsuitable for his stock, overlaid with insistent electric guitar music. Then, during the closing credits, Furtado reveals the fictional aspects of the film (some of the people onscreen were actors, the film was actually shot on an island nearby the Isle of Flowers), to conclude with an unambiguous political declaration: THE REST IS TRUE. And it continues to be so.