Roger and Me

Brendon Bouzard on Who Framed Roger Rabbit

Every filmgoer’s got a first love; mine was a rabbit. With his overly soft features, willowy body, and vaudeville-hell costuming, Roger Rabbit was a discreet, loving parody of character design from the golden-age of Hollywood animation; his obnoxious catchphrase (“P-b-b-b-b-blease!”) and manic, Jerry Lewis-like destructiveness were expressions of his inability to function in human society. And I had all the Roger Rabbit merchandise I could find—a talking doll, a towel, an NES cartridge of such low quality that it makes me angry to this day, and my prized possession, a videocassette of the original Robert Zemeckis film, which I probably watched as a young kid at least two dozen times.

I’ll spare you further trips down memory lane. Simply put, it’s remarkable how many of my memories of watching Who Framed Roger Rabbit as a kid are tied to these extratextual fetish objects. That talking doll—which broke within a month and only spoke at a normal speed if you manually slowed the pull-string—and the ill-advised video game speak to the cavalier manner in which films of the post-Ewok era were treated by their studios as first steps toward extensive tie-in licensing. But for all fifteen minutes of mild pleasure these buy-me-that-too toys furnished, none could compare to my proud ownership of the VHS tape, with its cover image of Roger (voice of Charles Fleischer) planting a wet one on the cheek of Eddie Valiant (Bob Hoskins) and an assurance that the film had received four ‘Academy Awards,’ whatever those were.

I owned Who Framed Roger Rabbit—we use this sort of discourse even now, though we usually acknowledge the essential facsimile nature of home video by throwing the words ‘a copy of’ in there. Home video affords the viewer a degree of implied primacy over the text—fast forward (or skip chapters, now) to “the good part,” rewind to see it again, pause for a bathroom break. It takes this nearly intangible surreality—the moving image projected on screen—and places a reasonably accurate copy of it within an easily portable plastic casing.

It’d be overly simple to label this as some sort of epochal shift in viewer-text relations that inexorably changes how my generation views the medium, and far too strong a concession to that most tempting academic fallacy—technological determinism. After all, home video suited (and continues to suit) a market demand; the seeds of whatever long-lasting cultural and economic impact it’s enjoyed lies in the fact that viewers basically want to possess these films, and possessed an unconscious desire to even before the technological and commercial frameworks that made such products possible.

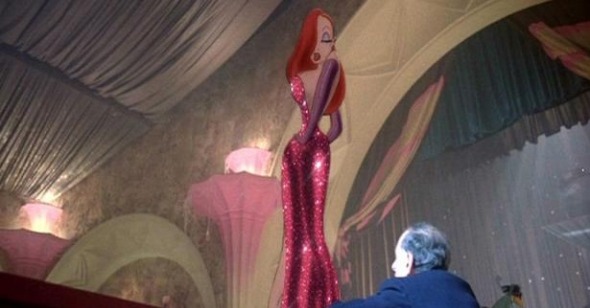

VHS certainly granted me a certain degree of autonomy over my childhood experience of Roger Rabbit—the ability to speed to my favorite scenes, rewatch the dazzling opening cartoon, skip past the scary part (in which Christopher Lloyd’s Judge Doom places an anthropomorphic shoe into killer Dip, accompanied by the shoe’s pained shrieking and a stylized, tableau-like close-up of Doom’s face), and above all, try to piece together what the hell was actually going on in this movie. For all of its accessibility as a complex visual wonder, the film’s narrative is replete with material that rendered it nearly incomprehensible for my five-year-old self in purely verbal terms: alcoholism, (not-so) veiled sexual innuendos, conspiracy, intertextual references to both classic animation and American noir, and surprisingly politicized discourses on ethnic America in the mid-20th century and the lasting legacy of the Great American Streetcar Scandal. Consider this: Who Framed Roger Rabbit was my first real exposure to Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny, and the entire host of the American character animation tradition. Moreover, without the foreknowledge of this tradition, I had no comprehension that Roger Rabbit, Jessica (voice of Kathleen Turner), Baby Herman (voice of Lou Hirsch), and Judge Doom weren’t as canonical as Bugs and Mickey; even at the time, my mind reeled at what a classic seven-minute Judge Doom short might look like.

The experience of coming back to a film after so many years—it’s been eleven or twelve since I saw this last, maybe?—is akin to reacquainting oneself with a childhood friend. Certainly we’ve changed—and no doubt they have too, and there’s a certain amount of trepidation at the prospect of finding fault with something simultaneously intimately familiar and impossibly distanced. Popping in the deluxe DVD of the film, with its stunning transfer in the original aspect ratio—my old VHS was, of course, pan-and-scan—and a surfeit of drool-inducing extras (storyboards, alternate art), I was confronted with the realization that despite telling people for years that Who Framed Roger Rabbit was one of my favorite films, I was almost completely unfamiliar with the film’s formal elements, except for the basic conceit of Toons seamlessly integrated into live-action footage.

Codirected by Robert Zemeckis and Richard Williams—the latter handled the animation—the film floats between registers in a way that thoroughly justifies my childhood inability to follow the plot. The opening, a Roger Rabbit cartoon called “Somethin’s Cookin’,” which borrows equally from Tex Avery’s character animation—the outsized expressiveness and unbridled sadism—and the work being done on shifting perspectives throughout the 1980s (as in Osamu Tezuka’s mindblowing first-person short Jumping), is a technical marvel, even more so when the fourth wall breaks to reveal Roger and Baby Herman on a set, Roger having flubbed a take. Having dabbled in animation, I now reflect on the sheer virtuosity of the craftsmanship: the constantly shifting perspectives in “Somethin’s Cookin” serve as a sort of warm-up for Williams and his animators in anticipation of the difficulties Zemeckis would give them. As a child, Zemeckis’s constantly moving camera didn’t really register with me as it does upon viewing it now—and the technical challenge of having to work the animation around a camera that is continually in motion is astonishing. And yet the film’s address continues to widen, following a burnt-out alcoholic private dick whose racist antipathy against the Toons slowly subsides when presented with a clear case of injustice in progress. The character of Eddie Valiant, his name a sort of Screenwriting 101 key to his role as protagonist, is made remarkably nuanced and indelibly human by Hoskins, who serves as the emotional anchor for the entire film.

At a certain point, my mind has begun to anticipate every coming action in the film—though I haven’t seen it in over a decade, whole scenes’ worth of dialogue and action are coming back to me seconds before they appear onscreen, allowing me a certain passive viewing experience that lets my mind wander through the layers of buried treasure the filmmakers have snuck in for fans: the song Roger sings at a bar is set to the tune of “Merry Go Round Broke Down,” Cliff Friend and Dave Franklin’s 1937 novelty song that became the theme music for Termite Terrace’s Looney Tunes series. Cameos appear throughout—some of the more abstracted elements from Fantasia end up as wallpaper and other interior décor in various scenes, and a list of Toons with off-color names produced by a drunk includes Dinky Doodle, a silent-era Walter Lantz (Woody Woodpecker) creation for the Bray Studio.

For some time in the mid-Nineties, it seemed that conservative action groups released findings of objectionable material in contemporary Disney film nearly daily, part of a larger anti-Disney movement spurred by the American Family Association to punish the company for their annual Gay Days at Walt Disney World. Though it’s obvious that it’s the priest’s knee and not his boner in The Little Mermaid and that Aladdin doesn’t tell teenagers to take off their clothes, perhaps most infamous of the many ‘discoveries’ was the revelation that some anonymous in-between animator saw fit to slip in a shot of Jessica’s cooch as she flies out of talking cab Benny’s door during a late-in-the-film action sequence. Loaded with this sort of distracting, experience-changing information, the likes of which might have had an unpronounceable effect on my childhood, I can’t resist the temptation to freeze frame the DVD during this sequence to examine the digital manipulation implemented to block the offending vagina. I don’t know what exactly I expect to find; the absence of the frames in question is pretty evident, but am I supposed to be able to detect some sort of evidence of the bowdlerization? It occurs to me that this anonymous frame, interchangeable with all the others in the sequence, is the only digital effect in the entire film, the last great effects picture without any CGI.

There’s a degree to which the dependency on technological innovation that characterizes much of Zemeckis’s cinema abnegates the political and spiritual conscience of his mentor Spielberg. Even his most conscious attempts at producing important works—Forrest Gump and Contact—are so in love with their own pictorial imagemaking and novel whiz-bang that they serve as autocritiques. Gump’s self-consciously parodic folk narrative about the rise of Reagan’s America teeters on instant-nostalgia banality with its famous digital manipulation of historical footage. Contact’s Reader’s Digest ruminations on the possibility of a Higher Power subside in that film’s second half to the dazzling wonder of human technical wizardry.

And yet Who Framed Roger Rabbit, at its time the most expensive American feature ever, reflects a sort of richly subversive quality at once aware of and transcending its parodic historicism. Astutely alert to the political machinations that shaped modern Los Angeles (Zemeckis borrows scenes and style from Chinatown), Who Framed Roger Rabbit casts light on the purchase and termination of most of the country’s electric-traction streetcar systems by a consortium of interests in the automobile and oil industries. The culprits of that mid-century scandal are masked here by the fictional Cloverleaf Corporation, of which Judge Doom is the sole stockowner. But Zemeckis wants to spread the blame: Doom’s ecstatic speech on the beauty of his freeway project—if Lloyd hadn’t ever done another movie, his legacy as one of America’s great character actors would be cemented here—is a darkly comic inversion of Mencken’s “Libido for the Ugly” that redirects the onus of the scandal toward the American public whose postwar suburbanization and aesthetic soullessness provided justification for the construction of “wonderful, wonderful billboards reaching as far as the eye can see.” In this sense, the film is nearly Sirkian in its indictment of the suburbanites who made up the film’s core audience.

Like Mencken’s, Zemeckis’s is the voice of an angry reactionary speaking on part of a falsified and nostalgic cultural history (Back to the Future and Forrest Gump work in similar territory), but unlike Mencken, Zemeckis makes some attempt to address the ethnic American experience. Maybe the film’s most self-consciously political conceit—substituting the Toons as a sort of ethnic minority whose enclave is imperiled by postwar suburban development—is a double-edged sword. Coy, subversive allusions to a troubled American racial history abound: the Ink and Paint Club, at which Jessica sings but Toons are prohibited as customers, is of course modeled after the Cotton Club, and taken to its natural extension, the entire premise of the film seems to be an denunciation of the racial profiling that leads to Roger’s persecution. Those sequences in which Toons are killed or imperiled by the Dip that troubled me so much a child continue to disturb me now—parallels to any number of racial and ethnic genocides are not unwarranted, though, given their context perhaps a tad flip. But the unintended consequences of the film’s racial discourses are troubling—are we to read the evil Toon-in-disguise Judge Doom as some sort of race traitor driven to ‘passing’ and sociopathy by his own self-hatred? To describe this as disquieting is an understatement, especially since in the non-alternate reality version of American suburbanization, it was precisely whites’ fears of minorities that led to the postwar exodus Doom’s trying to profit from.

Yet for me viewing Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and the naïve joy, finely wrought anticipation, and emotional catharsis of its perfectly constructed classical narrative, is such an emotionally fulfilling experience that it seems ruthlessly cynical to wring it through the same “ethical dilemma” evaluative grinder that allows me to dismiss a film like United 93 or Babel. Perhaps the lasting legacy of home video on this generation of criticism is that by democratically allowing writers repeated access to works, video privileges close textual analysis of a sort that forces the viewer to become more aware of internal inconsistencies or problematic discourses within a text. In a way, it allows us an autonomy over the text comparable to the one I enjoyed as a child—the ability to scan frame-by-frame, focus on particular experiential aspects of a film, and glide over that which contradicts one’s thesis (the scary parts). If my analysis of Roger Rabbit’s racial ethic seems pointless or absurd, it’s because there’s a recognition of a lesser representational burden on the film given its generic and stylistic qualities. It’s a fantasy about the transformative power of fantasy, a loving act of cinephilia rich with a brand of intertextual hijinks that pays tribute to and expands the craft of animation. And it’s a hell of an introduction to the medium for any five-year-old kid.