Black and White

By Travis MacKenzie Hoover

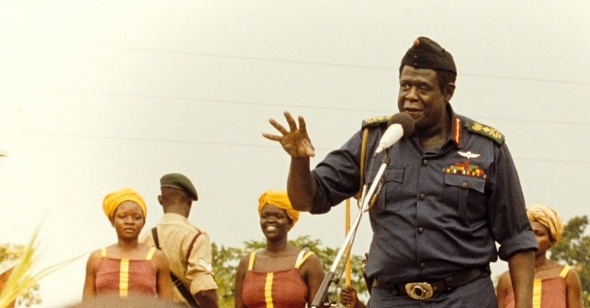

The Last King of Scotland

Dir. Kevin Macdonald, U.K., Fox Searchlight

In one sense, The Last King of Scotland is a perfectly serviceable night out. Barring the fact that you have to be primed for blood and ghoulishness, there’s nothing that should keep most people from being thrilled by Forest Whitaker’s Idi Amin Dada impersonation and the attendant madness that marked the dictator’s reign. The film is well, if unremarkably, directed, and there’s none of the smug piousness that tends to infect Hollywood liberal depictions of Africa. Still, you’d expect a film devoted to Amin’s legacy of bloodshed to parse the hundreds of thousands of his countrymen who died so that he could indulge in his grandiose lifestyle (and paranoid fantasy life). But the strongman is not only the main event: here, he’s also the one Ugandan character who’s even moderately differentiated from a sea of nonentities.

The audience for the film (and presumably Giles Foden’s source novel) is quite safely white—though to be fair, our point of entry is hardly the crusader of weak liberal legend. Nicholas Garrigan (James McAvoy) is more an adventurer, a newly minted doctor who wants to escape the stifling righteousness of his own father through the vague imprimatur of “doing good.” Thus he spins the globe and points to Uganda, winding up in the charge (and eventually the bed) of more solidly based relief doctor Sarah Merrit (Gillian Anderson). Merrit is slightly disturbed by Garrigan’s non-approach to Ugandan politics, especially when he is complacently impressed by a visiting, fresh-from-the-coup Amin. A fateful encounter on the road occasions our hero’s decisive shooting of a dying animal, and the impressed dictator immediately hires him as his personal physician. Thus the total ignorance of a dumb white guy lands him a seat at a table where no sensible person would ever want to sit.

This is supposed to be a demonstration of Western paternalism getting its just desserts, but the film isn’t quite thorough with its thesis. Amin is initially (and predictably) fun to be around, even as he hands Garrigan more state responsibility than he can handle, but he soon turns out to be the “madman” of press-release legend, one who murders close confidantes at the slightest hint of their nonexistent treachery. And as we never get out of the palace gates (save for an episode where Amin is nearly ambushed and killed), we never really see the extent of his monstrous reign—he’s pretty much the stand-in for Uganda itself. Save for a few terrified aides and Amin’s third wife Kay (Kerry Washington)—the latter of whom will have a fatal dalliance with Garrigan that will leave her pregnant and a plot device—it’s the flamboyant strongman who is our closest encounter with a nation and its people.

And given the traumatic nature of this encounter, one gets the distinct impression that the only winning move in the African game is not to play. The film becomes less a white man’s dawning awareness of his bad assumptions and casual arrogance than a throwing up of arms and saying “get me out of this burg!” Most of the final third is just a catalogue of Garrigan being terrified by dictatorial behavior: he and the film have given up on the “doing good” mantle and have zeroed in on the bread and butter of the movie, which is Amin’s certifiable, Hannibal Lectery nuttiness. True, the film has cruelly disabused its protagonist from the doltish assumptions with which he started off, but it hasn’t filled the void with any sense of responsibility: he just wants to get out, and in an eleventh-hour scene where non-Jewish hostages from a hijacked plane are being released from captivity, he’s given an opportunity and flies the coop.

Just prior to that safe passage, Garrigan asks his (black) savior why he’s putting himself at such risk. His answer: “I don’t really know.” He’s not the only one. This isn’t the statement of a character so much as one more plot device offering himself up as a sacrificial lamb—and a movie that’s so locked into the antimony of naïve Scotsman/monstrous Ugandan. When the film releases its final title crawl detailing the murder of 300,000 Ugandans at Amin’s hands (and that the people rejoiced at his 1979 ouster), you have to shake your head in disbelief—it’s a rare example of piousness after what has been essentially a horror movie. To pretend at this point that the film is spittle in the eye of tyranny is to deny the film’s own fascination with the “charismatic” Amin, as well its washing of its own hands.

I’ve painted a fairly damning portrait of the film, so I should backtrack: if you must see one Western-encounter-with-Africa movie this year you could do a lot worse than this one. That is to say, you could see the wretched and offensive Rwandan genocide hand-wringer A Sunday in Kigali, which I’m ashamed to say came from my home country of Canada; there the assumption of doing good, as enjoyed by Garrigan, is deployed with total obliviousness and without a shred of self-awareness. It’s also one of the ugliest movies of the year; The Last King of Scotland is at the very least dimly aware that charging in to do good is no real goal without a clear program to back it up. But to say that this movie has a program would a bit more than it deserves. Like a lot of Hollywood’s so-called political films, it stops dead when it actually has to offer more than just than saying “Dictators bad.” For it to delineate just how a dictator ascends to his seat of power would have justified Last King’s existence, but that’s more than this entertaining but empty film can muster.