Version 2.0

by Vicente Rodriguez-Ortega

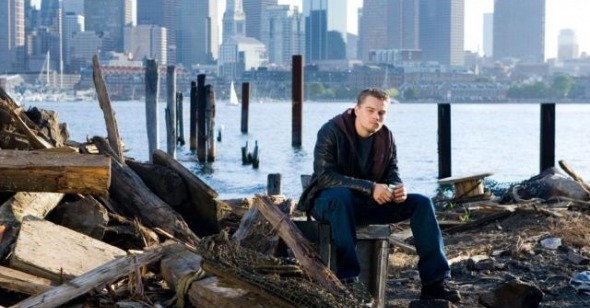

The Departed

Dir. Martin Scorsese, U.S., Warner Bros.

Don’t let anyone fool you: Jack delivers. Scorsese does too, for the most part. Lamentably, and somewhat complying with those who repeatedly pointed to the fact that The Departed is not a “Scorsese film” but a “Studio Job,” the Italian-American director occasionally loses grip and the film mutates into a run-of-the-mill, out-of-pace episode of CSI. Otherwise, the follow-up to the grandiose and lavish spectacles of Gangs of New York and The Aviator is a darkly comic and blood-filled gangster film that runs strictly by the book… plus cell phones. (As a friend sarcastically pointed out to me, The Departed might be, after all, “a dark comedy about cell phones.”) But, unlike series such as Vanished or 24, and even Infernal Affairs, upon which this film is based, Scorsese’s film refuses to fetishize the instruments of technological surveillance both organized crime and police employ and, instead, strategically makes use of them to ultimately reveal their insufficiency to comprehend the violent honor and betrayal the film depicts. Because, while allowing young blood to infuse the look, dialogue, and story of the film with dotcom generation sensibility, Scorsese goes back to the reliable basics of his latest works to anchor The Departed:

1) A childhood scene that delivers a revelatory insight on the psychological identity of one or several main characters, as seen in “the blood stays on the blade” opening of Gangs of New York; the bathing scene in The Aviator.

2) The unavoidable presence of Catholic symbolism, this time curiously associated with Frank Costello (Jack Nicholson), especially in his final moments

3) An in-your-face allegory that centrifugally extends the universe of the film into our current geopolitical era (think about the painful concluding dissolves of Gangs of New York). There’s a final little visual joke involving a rat in the foreground and the Boston State House dome in the background, which seems a tad gimmicky, as well as a cheap throw-in.

However, despite its misplaced political artillery, there is plenty to celebrate in The Departed. Scorsese is back where he belongs: the down, dirty, and mean streets of the urban jungle. In addition, the almost all-male cast—with the exception of Matt Damon, who has remained stuck in his Ocean’s Eleven role for the last few years and produces the same amount of facial expressions as Derek Zoolander—deliver magnificently. From Mark Wahlberg’s controlled verbal outbursts to Martin Sheen’s earnestness to Alec Baldwin’s schizoid vulgarities to Leonardo Di Caprio’s compassionate toughness to Ray Winstone’s quasi immobile fierceness to Jack Nicholson’s beautifully pure excess, The Departed is indeed an performance-driven, fast-paced comedy of expertly timed thrills (or comedic thriller, depending on your point of view) peppered with several instances of acrobatic verbal witticisms, and topped with enough generic clichés and predictable screw-turns to make it palatable for all audiences (yes, even those who paid money to see Ashton Kutcher and Kevin Costner’s The Guardian).

Perhaps what The Departed ultimately signals is the newly privileged status of the transcultural remake in contemporary Hollywood. It’s not as simple as “no one in Hollywood has ideas anymore” or that the industry just remakes older American films or scavenges other national industries for their most successful enterprises (Vanilla Sky, The Ring, The Grudge and so on). We may want to think in reverse and acknowledge that the extremely profit-driven and tremendously successful Hong Kong film industry has traditionally been characterized for its constant appropriation of a wide spectrum of narrative and audiovisual devices and even story lines derived from Hollywood cinema. And Scorsese was undoubtedly a key stylistic influence for two of the most direct precedents and palpable influences (John Woo’s The Killer and Wong Kar-wai’s As Tears Go By) for the film he himself has ended up remaking.

In short, if we carefully examine the state of contemporary cinema, we easily acknowledge that even though there is a defining economic and technological imbalance between Hollywood and the rest of national film industries, first, it would short-sighted to understand Hollywood cinema as a monolithic structure which survives through the repeated performance of a practice of top-down cannibalism. Second, Hollywood and other film industries feed off one other through a series of dynamic exchanges (ask Mr. Amenabar what were his major influences in the making of his nationally and internationally successful Tesis and Open your Eyes). In addition, the grassroots fan base for East Asian films such as Infernal Affairs has exploded in the West even if these films are not widely released theatrically, creating an already existing interest group for the American remake. The flourishing of the remake in our contemporary era is, thus, neither the result of an intellectual or creative vacuum in the bowels of the Hollywood giant nor the proof that if it wasn’t for the constant brain drain of other national industries Hollywood performs, American cinema would lose its privileged status in the world film panorama.

It signals, though, the increasing insertion of cinema within a broader cultural and technological public sphere that is growing increasingly powerful via the expansion of the World Wide Web and its derivative species (blackberries, cell phones etc.). “I don't want to be a product of my environment,” Nicholson tells DiCaprio “I want my environment to be a product of me.” The Departed is indeed a product, even perhaps an exemplifying instance, of a dominant trend in current cinema. While visually and aurally well-crafted and a great acting battlefield, it still falls short in escaping its origins: Despite the painstaking translation of the film’s story from Hong Kong to the streets of Boston, the film ends up being too literal, too respectful of Lau’s Infernal Affairs. A translation should always take its “original” as a point of departure from which to build a whole different work of art, not as a sacred text to be faithfully respected and imitated. The minds, hearts, and pockets behind The Departed seem to have been either too scared to try out such deviation, or too artistically blind to see that what they were doing flirted with the possibility of grandness.

Read the Shot of The Departed here